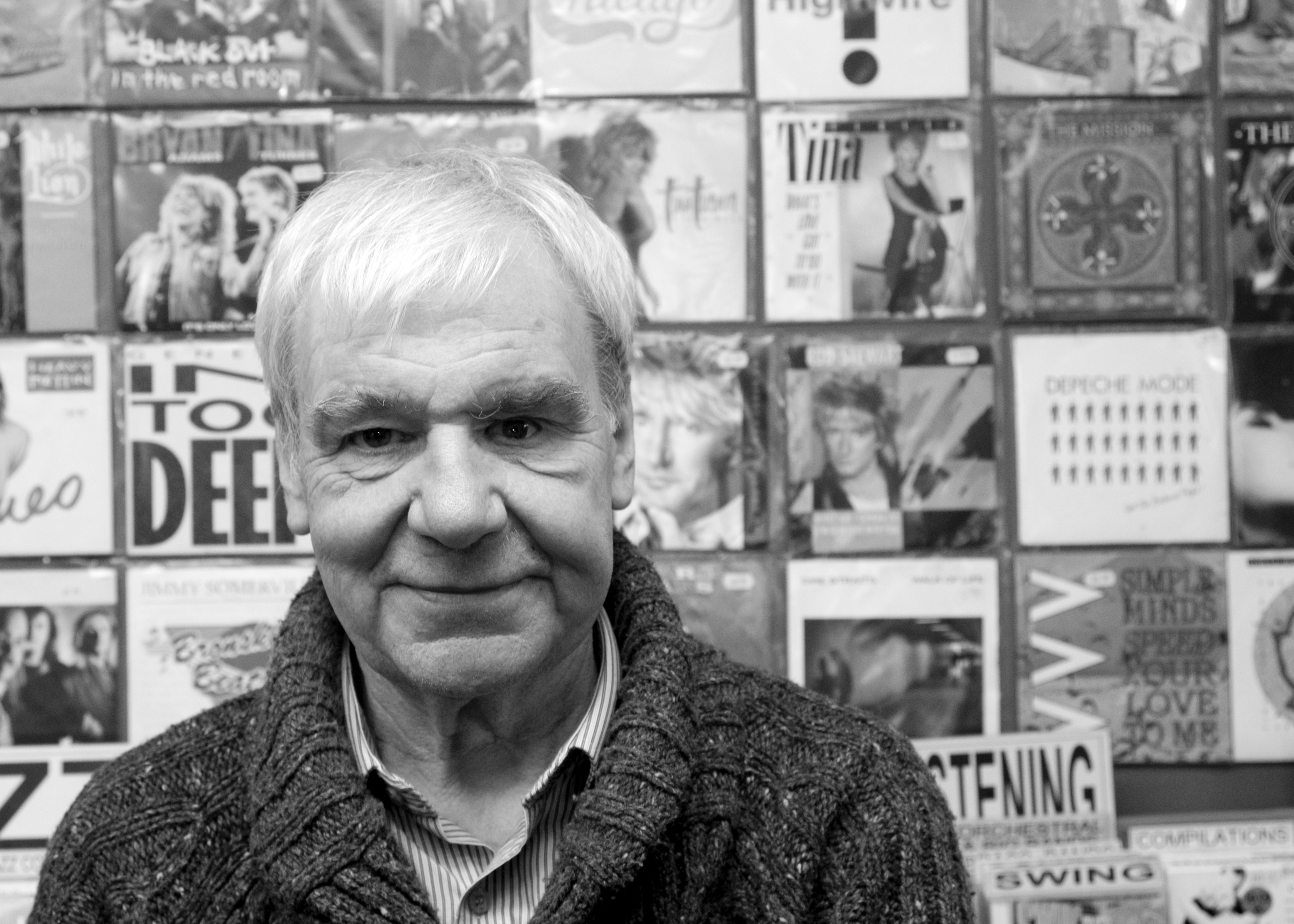

Having gone from strength to strength over the last decade and a bit, Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival has all but cemented its reputation as the most versatile and wholly immersive arts festival in Northern Ireland, if not the whole island of Ireland. As it prepares once more to dominate Belfast night-life and enthrall thousands across ten days of lovingly-selected, boundlessly exciting music, art, comedy and everything in between, Brian Coney sits down with CQAF organiser from day one, Sean Kelly, to discuss what’s in store and how the country’s most loved annual arts festival came to be.

______

Hi Sean. From a general point of view, what does this year’s Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival have in store?

“I’m very excited about how the programme has come together. We’ve secured a number of artists who, in my view, are really on top of their game. John Grant is coming on the back of his great new album, Pale Green Ghosts, Edwyn Collins has a new album out, Understated, which is lovely; Dexys put out an album at the end of last year, which is absolutely amazing, and then we’ve got some great comedy like Daniel Kitson, Mark Thomas, Sean Hughes and even Roy Walker – who’s an absolute legend – and some great literature like Will Self and Robert Fisk. Sometimes there’s a bit of luck involved and sometime it’s hard work but for whatever reason, I think it’s possibly our strongest programme to date.”

There is no question that the festival has went from strength to strength over the years. Did you ever envisage that it would last and evolve as it has?

“To be honest, no. I remember when we first came up with the idea of the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival people laughed. Donegall Street at the time was kind of tumbleweedville any time after five o’clock in the evening. The only kind of life in the area was the Duke of York bar, which is still there and thriving. The John Hewitt had just opened, so there was the beginning of a night-time culture but it was very undeveloped. Fast forward fourteen years and the area is probably the major social hub of the city at this point. It changed dramatically over the years.”

In those initial stages, what “alternative” do you feel you offered as a new-fangled arts festival?

“In terms of the festival, we were unsatisfied with the existing arts scene at the time. At that time, there was only really Belfast Festival at Queens, which was fine, but we felt in our youthful folly that it was very middle age, middle class, middle of the road and very south Belfast. We felt that there was a real need and an opportunity to engage with younger audiences and to present arts in a fresh and energetic way. We were very keen to take theatre out of traditional theatre spaces and visual art out of white-walled art galleries and try to break down a lot of the barriers to the arts that people see.”

Do you feel you brought people into an artistic milieu they may not have been interested or comfortable in otherwise?

“I do. Sometimes, still, I feel that people are a wee bit intimidated going into traditional theatre spaces like the Lyric or the Waterfront Hall and we wanted to present theatre, for example, in a much more informal and relaxed way. So we were putting on plays in pubs where people could smoke in those days and have a pint. We were putting on poetry readings in cafes and stuff and making sure that ticket prices were very affordable, which was important to us. For those reasons, people responded very strongly to the first festival and we decided to slowly build upon that from day one. Now we’ve become quite significant festival throughout Ireland.”

What struggles did you encounter in those early stages – and indeed down the years?

“People were kind of relieved that there was somebody doing something different in the city. I suppose it’s always difficult to reach certain audience, for example, in areas with very bad social deprivation, where there isn’t traditionally a high take up of the arts in general. So we tried to overcome that again by making our tickets affordable and putting on free events. I think physically putting our programmes and posters into areas that other arts organisations tend not to go to, and trying to go that extra mile to reach out to non-traditional arts audiences, I think we managed to overcome quite a few of the barriers in the arts but we’ll never get everybody. There are people who just want to go and watch football on a Saturday and that’s fine, but we do out best, you know?”

From a personal perspective, did you or anyone else feel inspired by other festivals or movements across the world whilst initiating the festival?

“I suppose one of our influences was the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. I’d been over to Edinburgh and used to come away from it very energised by the fact that every cupboard and stairwell in the city seemed to be turned into an arts venue. To me that was a revelation – that you didn’t have to do theatre in traditional spaces. I loved the energy that was in the Fringe and the fact that anybody literally could put together a show and put it in the festival. You didn’t have to spend five years at RADA or whatever and be part of this very established theatrical scene. I loved that open door policy that they have and the fact that anything goes.

If you go back fifteen years in Belfast, “the arts”, to me, seemed like a closed shop almost. I wasn’t from an arts background – I’d been a teacher – and it seemed that there was just these kinds of theatre companies and various arts organisations that were just kind of talking to themselves and were very inward looking. I really just wanted to blow that right open. There’s some way to go but hopefully we’re getting there.”

How many people are involved in the day-to-day organisation and running of the festival? From an outsider’s point of view it seems to run very smoothly.

“Well, the thing about the festival is it can only exist because we use to the skill and expertise of a wide range of people. We have consciously kept ourselves very light administratively, so that there’s only one full-time employee throughout the year – which is myself – and then closer to the time we bring in a great administrator – Cathy Young – and great press guy – Joe Nawaz. We also bring in a great crew to work on production. To be honest, though, you don’t need a big team these days. With technology being what it is, all you need is a computer, an internet connection and phone. I don’t travel anywhere, really, to view theatre shows or bands or anything because if I’m interested in stuff I can probably watch it on YouTube or listen to it on Spotify. We deliberately keep our overheads low so that whatever grant income we get from the Arts Council or City Council we can put it into the programme. It’s possible these days to run what looks like quite a big organisation actually with very few people.”

Two of the biggest acts this year are Dexys and Adam Ant. Do you think people are interested in shows like these as a direct result of nostalgia or a present-day interest in these acts?

“Well, there’s a couple of things going on there. I would say that we don’t just do retro acts for the sake of it – there has to be a reason for doing it. The reason n both of those cases is they have really good albums out. But in looking over this year’s programme, in particular, there seems to be quite a retro feel to it. It’s not a bad – there’s a lot of promoters in Belfast now promoting cutting edge new music. I think that’s great. There’s an availability of music that there would never have been available twenty years ago. But actually, sometimes I feel that the forty something age group, who used to go to a lot of gigs twenty years ago – who are now maybe married with kids and don’t get out an awful lot – are, to some extent, overlooked a wee bit.”

I agree. By that same token, a lot bands who could possibly be accused of being “nostalgic” just because they still exist – a lot of young people are getting into them, as well.

“Exactly. Dexys, for example, have cast a huge influence on bands. The Fall, who we’ve got, you can trace their influences right across the board. These are kind of iconic figures – Edwyn Collins and Orange Juice, their legacy is huge. But we try not to overlook newer bands and when we have the bigger bands coming in like that we love giving support slots to new and emerging local bands; to give them a platform on the local stage. And we have a big night planned that I’m looking forward to with And So I Watch You From Afar, who are curating a night of four bands, including themselves. It’s important that we do recognise the great bands that exist locally and give a platform where we can for that.

We can’t do too much of it because, you know, there’s a lot of local band nights available throughout the year and we have to balance supporting local music with bringing bands to Belfast who wouldn’t otherwise come. A lot of the bands that we’re putting on probably a commercial promoter wouldn’t touch because tickets sales wouldn’t be commercially viable. So we take a bit of the grant money that we get and say, “Ok, we might lose a couple of grand on this but we think it’s important that the Fall come to play etc.”

Over the last few years, do you have any personal highlights from the festival?

“Over the years a couple of shows have stood out in my mind. I still would say that the greatest show that we ever presented was Patti Smith at the Art Council – that was going back to 2003. I wasn’t intending to stay because I had to go somewhere else but I was just rooted on the spot – totally mesmerised by her. She was an absolutely amazing performer; you just couldn’t take your eyes off her. So that’s probably my all-time favourite gig but there’s been a rake of them over the years. Some of the best ones have been in the Black Box. We got involved in helping to set up the Black Box nearly seven years ago because, as a festival, we needed a room about the size. To me, it’s almost the perfect venue, just in terms of the size, the acoustics, the atmosphere, the staff – everything. I’ve stopped going to big, big shows; the last “big” show I was at would have been Springsteen down at the RDS around five years ago and I remember there was a crowd of about 40,000 there and I was in the middle of them and I felt totally unengaged, really, with what was going on in the stage – essentially strain to watch a big screen. I realised at that time that that scale of gig wasn’t for me anymore. The biggest gig I want to be at is probably 500, 600 people, you know?”

Finally, for people who perhaps aren’t overly familiar with the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival, what would you say to be people who are curious but uncertain about checking out a show here and there?

“Well, I think we’re all feeling the pressure these days, economically, and we all probably go out less than we used to. And it’s not surprising as ticket prices have gone through the roof and going to a show these days is not a cheap experience. But we’ve worked very hard to make our ticket prices as affordable as possible. You can see legends like Mark E. Smith for twelve quid; you can see Dexys Midnight Runners with a full ten-piece band for fifteen quid; you can see Will Self for six quid. We’re trying to put on really high quality shows that are within the budget of most people. If you’re only going to go out a few times over the next few months, make it the Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival one of those times at least because the shows are high quality, the staff are friendly and we’ve got a great bar set-up in the Marquee which is sourcing all local beers. We’re going the extra mile, we’re keeping the pints under four quid – which is unheard of these days – and as long as people come to the shows, the festival will remain viable and hopefully we’ll be here in another fourteen years.”

Cathedral Quarter Arts Festivals runs from May 2-May 12.

For more information about tickets, line-up etc. check out the CQAF website.