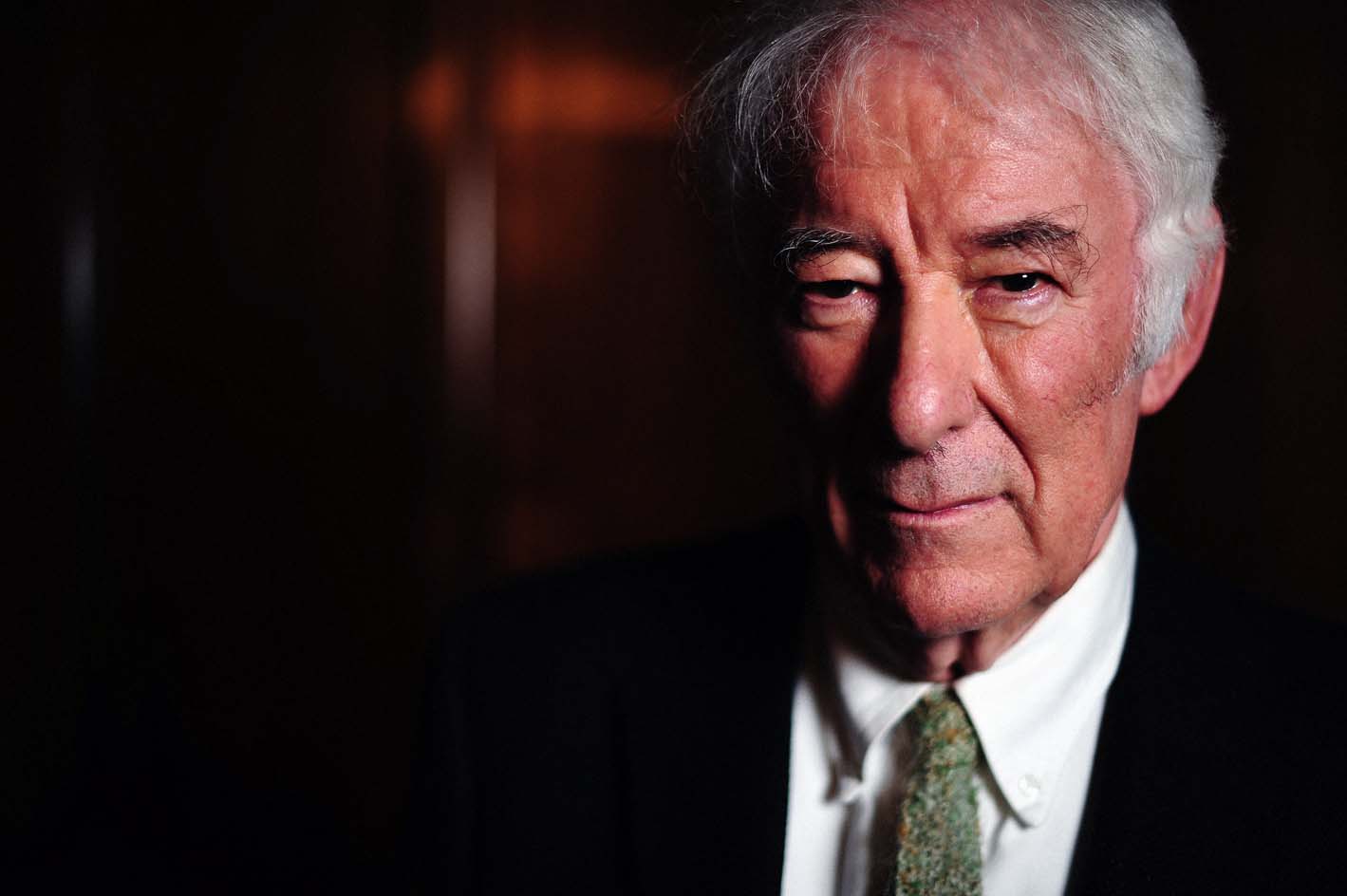

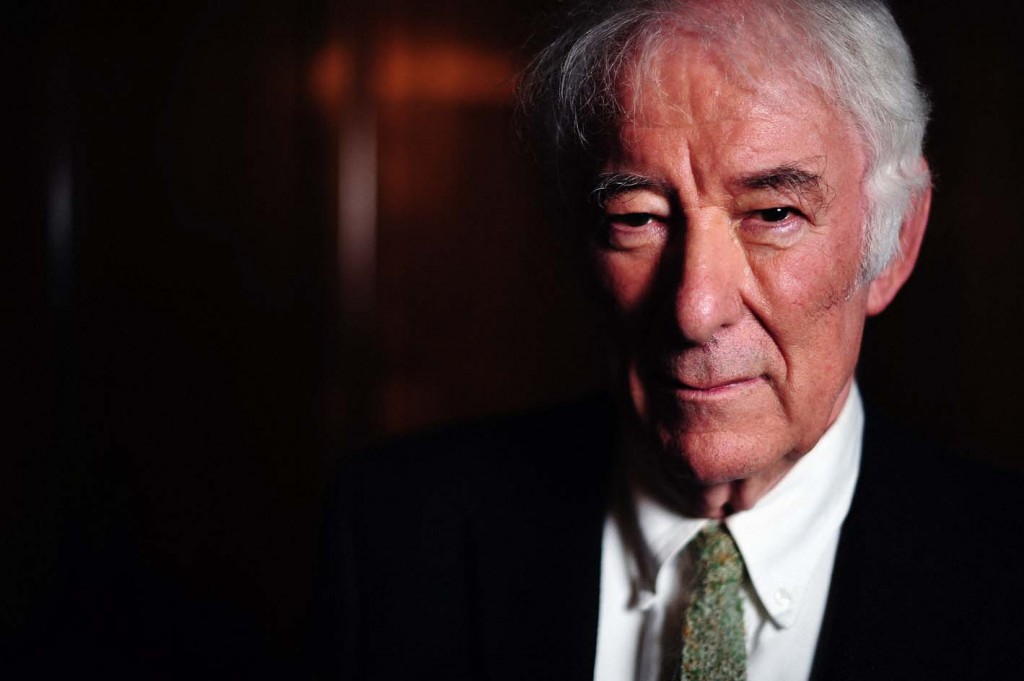

How do you write words for the master? Is it possible to pay tribute in language to a man whose legacy is to have captured the very essence of our soul in words? Perhaps not, but for all the words that Seamus Heaney put to paper, it’s a safe bet that over ten times that will be written about him in the years to come.

The Castledawson born poet has been hailed as the greatest Irish poet since William Butler Yeats, an iconic figure, sitting comfortably in a pantheon of great Irish voices alongside Beckett, Joyce, Behan, Shaw, Wilde, and many others, It’s impressive company for a man to be part of, and it has served to add fuel to the ‘legend’ of Heaney, long before his death. Such myth-making is impressive, expected even, but obscures the man, and the work, in favour of some easy categorisation that will sadly reverberate down the ages.

So there he is, tweed jacketed, tousled hair, striding through peat and boglands, absorbing the land, and connecting with the earth itself. Rustic, displaced from time, this imagined Heaney exists in a land where Northern Ireland is perpetually a rural paradise, where boys and girls play in fields, and men have ruddy cheeks, a kind of Ireland where it is eternally the sunshine days of the 30s or the 40s. Heaney – the proud Irishman.

But Heaney didn’t exist purely in this world. Death of a Naturalist, perhaps the volume for which he will always be most closely associated with, was published in 1966, the year that Bob Dylan confirmed his mastery of the electric blues form with Blonde on Blonde, and the year The Beatles released Revolver. To think of Heaney in his rustic finery, stick in hand, astride a hill, whilst Dylan whines electric verse into the neon night sky is strangely out of place, and Heaney, for all his connection to the natural world, was also a man connected to the modern world, and all that it entails.

And so it was that he found himself at Queen’s University in Belfast in the 60s, fraternising with other poets, with musicians, lecturers, with people who smelled revolution on the air, but couldn’t have seen what kind of revolution it was going to turn out to be. This is the Heaney who is in the midst of a cultural maelstrom, keenly observing the sectarian strife that is about to burst out into the open, and seeing the ever increasing divide between young and old that will fundamentally alter the way life in the western world is conducted.

Perhaps this is why Heaney’s loss is so keenly felt? Beyond his genius with language, his work stands apart from time, touching the fundamentals inside us, and helping us understand the world in which we live in? Heaney never really left behind his Irishness, but it was a contemporary Irishness, the kind that could see him explore Irish history through the prism of the Troubles, the kind of perception of identity that found him involved in the pioneering work of Field Day Theatre in the 80s alongside Brian Friel and Stephen Rea, and the kind of connection to home that continues to inspire and motivate contemporary Northern Irish poetry to this very day.

And as the tributes pour in from all over the world, social media, a method of communication that enforces the economy of language that Heaney so often displayed, but not the depth, has lighted up, casting out fragments of Heaney’s verse into the digital ether. This, for me, is the legacy that Heaney has left behind – a desire and a fearlessness to engage with poetry in those who need it most: the young. For all of us quoting lines, sharing words, and paying tributes to the man today, there’s a chance that Heaney is the one we don’t need to look up, the one whose words are etched upon our minds the deepest, and the one we never struggled to understand. In a world where attention spans are pummelled on a daily basis, this is no small achievement.

It’s a sad day for art, Irish art or otherwise, but the tributes paid are enough to give me hope that the flame of poetry has not gone out. And I can’t help but feel that this is one achievement that Seamus Heaney would be proud of. Steven Rainey