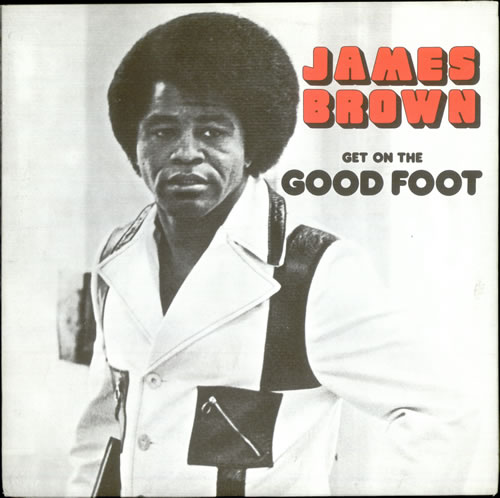

Lesser Known Pleasures is dedicated to celebrating great albums that are often overlooked in the hope of gaining them some more of the attention they so deserve. This time, from a surprisingly large choice of decent James Brown full lengths, Get on the Good Foot receives the LKP treatment for it’s breadth and because, for a funky pop album, it gets plain nutty…

It is perhaps fair that James Brown is considered a singles artist. From the mid-50s on he was responsible for an endless stream of 45s saturating the R&B market. Served up in what seemed like throw-enough-at-the-wall tactics (up to 10 a year!?) inevitably there was the superfluous, but the majority were iconic barnstorming classics. Consequently any “Greatest Hits” compilation has become an easy target for anyone seeking the essence of James Brown (an extremely lucrative essence were it ever bottled). Live albums too have come to represent Mr Dynamite in a neat package. The legendary and groundbreaking Live at The Apollo (1962) captured the energy of Brown and his ruthlessly rehearsed band better than most studio efforts ever could. The hysterical audience response sealed the deal. This was followed over the years by further, equally successful if less acclaimed live outings backed by an ever changing string of musicians.

Where does this leave the James Brown studio album? Did he even make any? Did he have time with all those singles and touring? Unbelievably, yes. He didn’t hold back either. From 1959 onwards, JB averaged around 3+ albums per year. 1966 alone saw the appearance of a ridiculous 7 long players. With that kind of output, it’s no surprise to discover a distinct lack of quality control. If you could afford to stretch for the LP instead of the single, you were likely to be disappointed. Typically you would be faced with the latest hit, followed by 30 mins of fluff for which the term “filler” may actually have been invented. So scan the ubiquitous Best Albums Ever lists and, depending on the strictness of their rules (comp and live albums are sometimes excluded), you may find The Hardest Working Man in Show Business under represented or even notably absent.

A decade of largely dispensable releases earned Brown an understandable reputation as a non-album artist. It’s a reputation that stands to this day. However the assumption that he never made any consistent studio albums at all is shockingly far from the truth. Times change and Soul Brother No.1 changed with them. Often he was ahead of the game, sometimes lagging, but like all truly great artists, knew he had to move on just to maintain. As the 60s progressed, the album as a format became more important and Brown accordingly began giving their content more consideration. This tied in with a development of his material – the groove took on a tougher more simplified edge resulting in the invention of funk and lyrically, a more socially aware angle was added to the usual dance-and-romance fare.

And so we come to the 70s. Following record company troubles and the walk out of his live band, he settled into the new decade with a new label Polydor, his new sound – funk and a new band The J.B.s. Crucially the quality control was more rigorous, even if the formula was similar – a hit plus a selection showcasing what James and his band were capable of at the time. Albums were restricted to a more respectable 2 per year, though were sometimes doubles – the first of which was Good Foot. By the time of it’s release in 1972, most of the original J.B.s had moved on to join Funkadelic. The remainder however, with a few of the 60s band returning were, as ever, a tightly drilled slick live unit.

Get on the Good Foot takes the early 70s formula and stretches it over a double album. It sounds like a recipe for a quick return to the shoddy albums of the early 60s but the result instead is something altogether different. Over four sides of vinyl, James Brown represents almost every aspect of his career to date and a few things he might not have expected himself.

He kicks off as usual with the hit single and title track, this time it’s a blockbuster, one of his most successful blasts of muscular funk. Not just “funky” anymore … this is pure funk. You know the thing: Deep thunderous bass setting up a single chord groove, two or three guitars trying to outdo one another as the catchiest rhythmic hook and horns assertively emblazoning their melodic blasts on top. JB himself weighs in with his usual grunts and screeches, mixing raps on dancing with some political commentary. 6 minutes later, cut to a more brief psychedelic soul experience followed by a traditional big band soul number. The side then finishes with an update of ‘Cold Sweat’, a hit from ’67. This was a common ploy at the time. The new James Brown funk sound was developing too quickly for his songwriting to keep up and he regularly introduced vintage numbers reworked in the new style. Some are way more successful than others but the original ‘Cold Sweat’ was a breakthrough in his journey to the funk, so the update is more about the new band’s delivery than the revamp and it kicks ass.

So a side down and you’d be forgiven for thinking it was business as usual but as Side 2 begins, all bets are off. ‘Recitation by Hank Ballard’ also pushes the 6 minute mark and is quite bizarre. Hank, a former R&B star himself, narrates what is essentially an advert/review of the album. It’s a boldly postmodern statement for the time and while it might interrupt the flow a little after a few listens the music behind Ballard’s waxing is worth a mention. It’s the kind of smooth yet dramatic instrumental vibe usually associated with Blaxploitation soundtracks. Brown, despite his obvious credentials, became a latecomer to the soundtrack business. Beaten to the mark by Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, Bobby Womack and of course Isaac Hayes he eventually weighed in a full 18 months after the latter’s Shaft with Black Caesar and Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off both in 1973. Whatever the reason for his tardiness, he proves here he wasn’t missing out on the zeitgeist.

After another solid funk groove in ‘I Got a Bag of My Own’, JB takes us right back. Right back to the sound that made his name in the beginning. Bringing the tempo right down, he delivers two Southern Soul ballads proving he can actually sing from the heart as well as the head, hips and groin. The first is a new song ‘Nothing Beats a Try but a Fail’ which drips feeling from its pours. The second, ‘Lost Someone’ is old enough to have featured as the centrepiece of the original Live at The Apollo album 10 years earlier and is equally as engrossing. Listening now it is astonishing how in these two tracks deliver (in the former’s guitar arpeggios, the latter’s string arrangement and emotional crescendo) a perfectly formed instruction manual for fellow Georgians R.E.M. to write arguably their signature song, ‘Everybody Hurts’. Check that out for yourself.

Side 3 is where things start to get crazy. Already having fired out two funk workouts at us that approach 6 minutes he now lets himself get carried away. Mearly two tracks take up the whole side. One new, one old, they are reproductions of Brown’s onstage extended jams, peppered with call-and-response with the band, shout outs to all and sundry, jokes, skits, routines, slogans and hooks. Anyone familiar with the live albums of the time will already be privy to these mammoth sessions but in studio form they take on a whole new colour. Live, the band and James as MC work the crowd, reacting to their energy and responding in kind. Without an audience, and bearing in mind the nature of the music, the repetitiveness of the rhythms and riffs, odd as it may seem, become Krautrock hypnotic. Though unintentional, it transforms funk into an avant garde exercise in minimalism. ‘Please, Please [Please]’, one of Brown’s oldest songs and originally an R&B hit lasting 163 seconds, breaks 12 minutes. Drugs may have been involved.

After that, Side 4 has to be the comedown. It’s no less impressive though. The J.B.s see out the album in instrumental mode and they do it in style. Brown himself steps up and shows his pedigree on his instrument of choice – a classy organ on which he displays convincing chops. The mood returns to the Blaxploitation vibe and things are generally chilled. Previous hits get a loungy workout and new number Dirty Harri shows the way forward to his soundtrack work and informs the majority of Beastie Boys’ instrumentals 20 years later.

Get on the Good Foot is not a perfect album because, yes, it’s sprawling, meandering and self indulgent. It is however, brilliantly so. As the 70s trundled on, The Godfather of Soul distilled his funk ever purer and in the process gradually phased out other elements from his palette. This album holds a unique position in his catalogue by representing practically his entire career in a single statement. With the addition of some scattered madness brilliantly if unconsciously symbolizing US social and political unrest of the time, it is a better account of James Brown than most compilations.

In a final note to illustrate his stock as an album artist, find yourself any of the James Brown studio albums dated between 1971 and 1976 (there’s about 15) and you will not be disappointed. That’s quite a run. Jonathan Wallace