I’m none too smart, a sumo-intellectual at best, but people often assume I am clever because of my large forehead, glasses and the fact that I talk far too much. My learning is skin-deep and a mile wide but I have a felicitous ability to put random things together in a manner that would answer Lautremont’s dictum: I can’t get any of my dissecting done as the whole place is lousy with sewing machines and umbrellas. But mostly what I like doing is showing off. And this is a record that really shows off. It is, if you like, a pseud’s charter.

During The Divine Comedy’s Promenade we will be dipping into the taxonomy of fish, given a short critique of 20th cinema, receive cameos from Aphra Behn and William Makepeace Thackeray (“call me William Makepeace Thackeray”) and God. We meet Chaucer’s Chanticleer, Salman Rushdie and Sebastian Flyte. And all of this is set to a musical background so indebted to Michael Nyman that a worried Neil Hannon handed him a pre-release copy of the album with the words, “You can sue me if you like!”

Hannon sings as Scott Walker recording Noel Coward instead of Jacques Brel. When he writes music he is Gordon Lightfoot assaying a passable Jake Thackray. Promenade was released the same year as Definitely, Maybe. This is not a Britpop record. It might possibly be a BenjaminBritpop record. There is a fair amount going on.

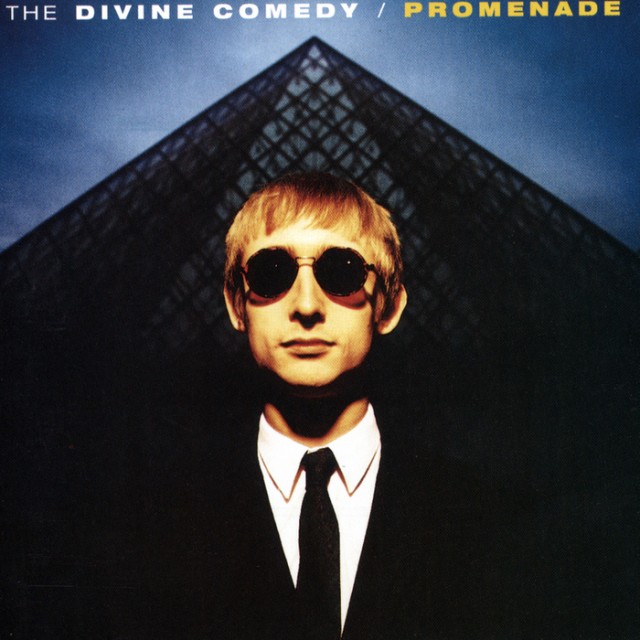

Hannon himself presents some difficulties. He is slight, he is elfin. He has the demeanour of a man who would not acquit himself well “should it all kick off”, all a bit iffy in the troglodyte 90s. He has, on Promenade, yet to chime with the zeitgeist, as he would with 1996’s Casanova, where he briefly bestrode two pop camps, Britpop and Easy Listening, like a spindly colossus (a spurt of public approval engineered entirely by Chris Evans. Which is something Hannon will have to live with for the rest of his life).

On Promenade he is a be-suited patrician presence, an old school cabaret singer: Matt Monroe had he not been styled “The Singing Bus Driver” but rather “The Singing Arts Graduate”. He’s positively donnish. This sonic smart-arsery is a turn-off for many, homophobes, say, or people who think that brains, like politics, “don’t belong in music.” But that, of course, is bullshit. I love this record and I love Neil Hannon. I recognise myself in his self reflexive archness, his auto-didactic need to show people how clever he is. It is a portrait of me and a diary entry on a legendary day, for Promenade is, of all things, a concept album; the concept being a day in the life of two lovers. It’s a busy day.

We open with the sound of crashing waves and Hannon reciting from Isaac Watts in his dolorous Norn tones: “Time like an ever rolling stream, bears all its sons away; They fly forgotten as a dream dies at the opening day.”

Then it’s straight into ‘Bath’, possibly the most Nymanesque track on the record with its simple, additive string parts, slowly building in intensity and complexity over the sound of crashing waves, until the drums kick in and we hear “Rub a dub dub, it’s time for a scrub.” It’s an effortlessly Neil Hannon moment. Our heroine, it transpires, is in the tub, scrubbing up for her big date, wiping away at the soap suds in her eyes while a clarinet goes at it, worrying away like one of those fish who pick the dead skin off your feet in voguish aquariums.

‘Going Downhill Fast’ is another pop song for prodded piano and string quartet. It tells the story of our protagonist’s bracing coastal bike ride, somehow invoking a bruising Russian choir along the way and sees Hannon really putting himself through his melodic paces, affecting some sterling pipe-work before a crescendo of glossolalia and tringing bicycle bells.

Hannon famously (and rather touchingly) sends all of his albums to Scott Walker (so Scott can stick them on his fridge door with a magnet, one imagines). ‘The Booklovers’ is the one that Scott liked on Promenade. It’s a list song, not unlike ‘A House’s Endless Art’, wherein Hannon introduces, in stentorian voice, the Western literary canon and the writers reply in kind. These answers go from the charming (“Gunter Grass: “I found snails”) to the decidedly dodgy (Kazuro Ishiguro: “Ah so, old chap”). The song is saved by its stately and dignified musicality and an intro by Audrey Hepburn from Funny Face.

‘A Seafood Song’ does what it says on the tin: songs in the key of tuna.

‘Geronimo’ might be my favourite Neil Hannon song (and he has written some crackers: ‘Victoria Falls’, ‘A Woman of the World’, ‘The Uncertainty of Chance’, ‘A Lady of a Certain Age’ etc). I suspect he doesn’t rate it himself as it remains so different from the things he tends to fall back on: the sonorous croon, the orchestral shake of the tail – Geronimo is lean. The song is breathless and pell mell; a silent screen hero racing for the train tracks through a squall of rain. Against a detuned piano and guitar it features the most affecting and simple lyrics on the album: “She puts on a record and sings into her coffee; he puts a blanket round her, sits her down and dries her beautiful hair”. Notice, also, that semi-colon. Neil Hannon’s punctuation is pristine.

‘A Drinking Song’ is not about water. Quite the opposite. Starting with a belch and the sort of rickety string quartet that Alastair Sim would blearily raise a glass to, this is probably the apotheosis of everything the Hannon haterz despise: a novelty song that sounds like Flanders and Swann played by the Houseguard’s chorus, finding the singer in full Bertie Wooster pomp, a staggering silly ass clutching a bottle of Lafite and a Bobby’s helmet. It’s a hard song to love, especially when Hannon starts singing back to himself in a “comedy” drunk voice, but you have to admire the quality of his song writing, his commitment, his brio or, at the very least, the sheer ability of his singing, even when what he’s singing seems to have you pinned to a wall like a spittle lipped party bore.

The album ends with live favourite ‘Tonight We Fly’, a piano led gallop, in which our lovers have achieved bliss and are so consumed with love that they become transfigured and fly through the night sky, “dogs barking at their shadows”. It is a beautiful end to a beautiful record and Hannon is in relaxed and handsome voice. When he’s not trying really hard to impress you, when he lets his chewy baritone work for him, it really is a thing of supple, tender beauty, with a mournful tone that all of the silly arsery can never quite chase away. That’s the thing about the The Divine Comedy: they mean it much more than they let on. Behind the smoke screen words and the dandy demeanour Neil Hannon is a genuine romantic fool. It’s there in his cracked bell of his voice, in the pristine classicism of his songwriting, in his inescapable interest in other people’s ruminations on love. He’s always trying to find a way into your heart and he’s going to use wit, charm, verbal dexterity or plain dicking about to do it. He’s cupid with a hundred different arrows in his quiver. One of them has got your name on it.

All art must present a mirror to its audience, and this record is a black vinyl looking glass. It is a Borgesian labyrinth, the needle touring the high walled obsidian channels with the inevitability of a bobbing turd circling in the white water. This is The Divine Comedy’s Promenade. John Higgins