In no uncertain terms, Prince is one of the most important musicians of the 20th century. Between 1980 and 1988 he released a series of albums that are still startling in their invention, originality, and scope. As a pop star, he remains an enigma, and as a performer he is arguably unrivalled. However, the last twenty years have not been kind to him, and as he stages another attempt at grabbing the public’s interest with the simultaneous release of Plectrumelectrum and Art Official Age, we look back at his 1986 classic Parade, and wonder, where did it all go wrong?

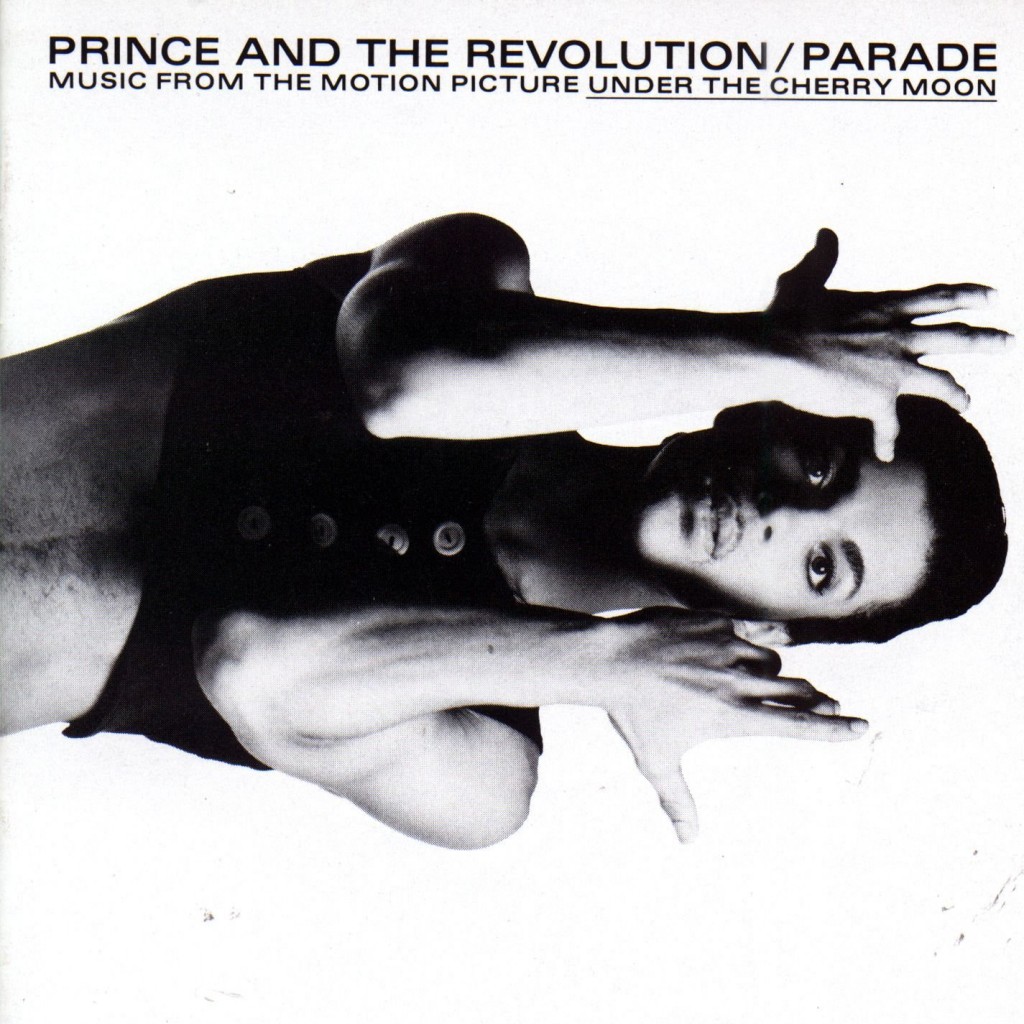

In many respects, Parade shouldn’t work. It’s the soundtrack of Under the Cherry Moon, the follow up to his smash hit movie Purple Rain (1984), and where that movie was a whirlwind tour through everything that made Prince appealing, Under the Cherry Moon was a narcissistic bomb that served little more than to alienate a sizeable part of his audience.

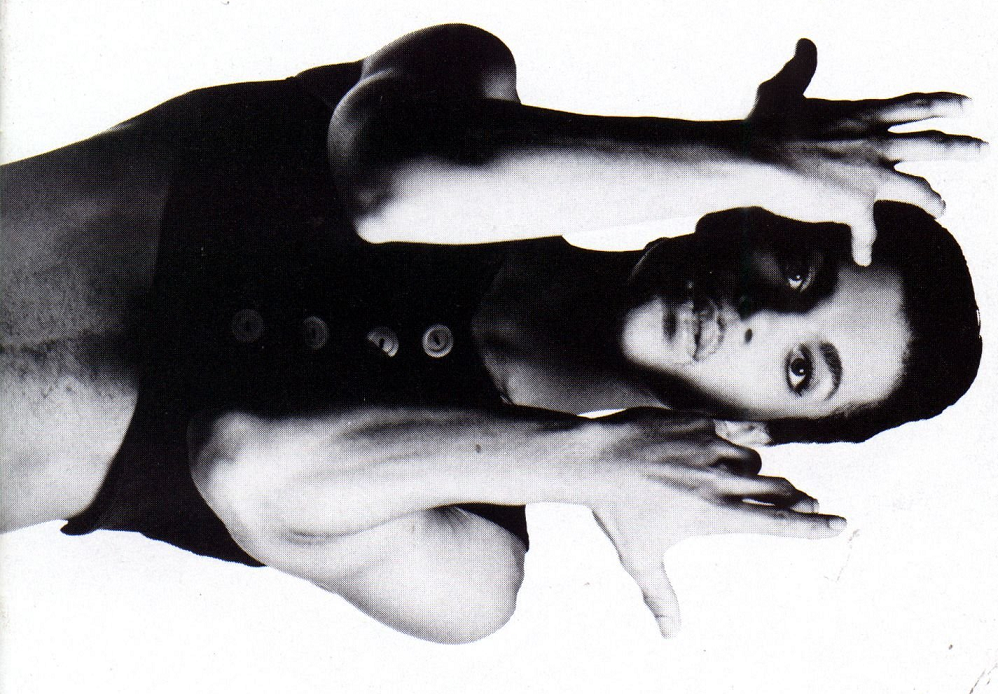

Looking back at it now, it’s still a problematic film, inherently flawed, right from its very conception. Discarding the “Kid” persona that served him so well in Purple Rain, the follow-up finds Prince cast as Christopher Tracy, a playboy huckster operating on the French Rivera. Shot in black & white, the film has a wafer thin plot, wooden performances, and an odd sense of dislocation as the 1920s setting perpetually clashes with the futurism that Prince is so much a part of. The fact that Prince is director as well as star doesn’t help, with the diminutive one proving expert at shooting loving, soft focus close-ups of his own face, but little else.

Parade, on the other hand, finds Prince at his very best, a kaleidoscopic assault on the senses, with much of what had made him successful in the first place casually thrown in the garbage can. Opening with ‘Christopher Tracy’s Parade’, the album starts on a bewildering note, a stuttering drum pattern ringing out over an explosion of orchestral noise, strings, brass and woodwind competing for space. Prince is lost in the middle, sketching out visions of “Christopher Tracy’s piano”, and a world where the predominate worry is that it should “Rain strawberry lemonade” or that the devil should run to his “evil car.”

It settles down into ‘New Position’, a skeletal funk jam, primarily centred around bass, percussion, and steel drums. Dancing on a skittering rhythm, Prince lets us know that we can’t last long “without a shot o’ new spunk” (cue lascivious laugh), and then urges us to try his new funk. And before we’ve really got a taste of what that is, we’re off again, ‘I Wonder U’ giving us a brief moment to breathe as it’s slight running time and spooky, but playful atmosphere do little more than mark the time.

The title track is a fairly insubstantial nod towards the supposed music of the era in which the film is supposedly set (this is all very loose, to be fair), and then Parade shifts gear entirely, as ‘Girls and Boys’ quite literally BURSTS out of the speakers. The song is mastered at a far higher volume than everything that came before, and the production is substantially more robust than the rest of the album. Intentional or not, it has the effect of waking the listener up, preventing them from getting too comfortable, and positively forcing them to pay attention.

Unfortunately, the song itself isn’t amongst Prince’s best, cruising along on a taut funk groove, but providing some utterly insubstantial lyrics. It’s a jarring mix; a song that is obviously designed to grab attention, yet rarely warrants it. However, it does serve to introduce the honking sax of Eric Leeds, and makes Prince’s debt to James Brown very overt.

More textural music follows, but on side two, things really step up a notch. With one glaring misstep, this is one of the strongest album sides Prince has ever created, a tour-de-force of funk rhythms, rock dynamics, post-punk experimentation, and pure, unfiltered creativity. Put simply, side two of Parade is a suite of songs that *only* Prince could have made.

‘Mountains’ is stunning, a rare outing for the full-band version of The Revolution. Despite having assembled one of the most accomplished backing bands in pop history, Prince still preferred to record most of his music alone, giving us scant evidence of what his band were capable of. ‘Mountains’ leaves us begging for more, a towering groove, shimmering along on waves of guitar, horns and keyboard textures.

‘Anotherloverholenyohead’ is cut from a similar cloth, a supremely confident groove coupled to an expansive use of sound and melody that just takes it into another dimension. ‘Sometimes it Snows in April’ is a beautiful tone poem, the piano of Lisa Coleman and the acoustic guitars of Wendy Melvoin forming chord clusters with Prince’s, as he outlines a meditation on life, death, love, and spirituality. It’s the perfect end to the album, and reveals a surprisingly contemplative side to the artist that he’d rarely taken the time to show before.

Slap bang in the middle of all this, side by side, is one of Prince’s greatest songs, and one of his worst. ‘Kiss’ requires no introduction, a visionary inversion of a conventional pop song, a controlled, skeletal blast of sexuality and humour that still sounds original to this day. ‘Do U Lie’, perversely, is a piece of throwaway rubbish that manages to greatly outstay its almost three minute running time. It’s further proof, that even when he’s at the peak of his powers, Prince is more than capable of letting it all fall down around him.

The album is infinitely better than the film it supposedly soundtracks (most of it only really appears as background music, if at all), and remains one of the most artistically ambitious albums Prince ever released. Sign O’ the Times and Lovesexy proved there was definitely still life in him yet, but after this album, Prince would disband The Revolution, and his music has forever lacked that sense of band identity, of players with an intuitive understanding of each other, and at the peak of her powers, despite their almost non-appearance on the records.

It’s almost as if knowing the incredible amount of talent he’d surrounded himself with was enough to propel him to greater artistic heights, and his subsequent albums in the 90s and beyond have found him making increasing use of session musicians, and lapsing into a generic and irrelevant sonic palette. Parade might not be the tightest batch of songs Prince has ever committed to tape, but it remains one of his most distinctive, and is a master class in what is possible when a supremely talented artist is given free rein to create his own sonic world.

That he has never really topped the artistic peaks of his mid-80s period is sad, but hardly surprising. For that incredible run of albums beginning with 1999 and ending with Lovesexy, Prince transcended genre and time, and has spent the remainder of his career trying to keep up with trends and shifts in music, all the while refining his muse to bland anonymity. That’s harsh, and many of Prince’s later records feature some incredible songs, but in a realistic sense, they’re just markers of his artistic decline. But when you have flown this close to perfection, you’re going to get your wings burnt off. And frankly, when you look at the riches he left behind on the way, it’s more than worth any price you’re prepared to pay. Steven Rainey