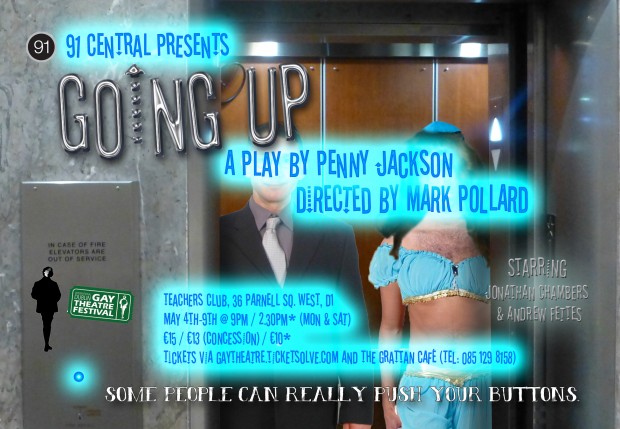

Amid chaotic preparations in shipping out from NYC to Dublin, playwright Penny Jackson sits down with us to discuss her success as a writer both on and offstage, the lead-up to the debut of her brand new show Going Up at this year’s Dublin Gay Theatre Festival, and how she believes in the power of theatre to foster social change.

Hi Penny. How’s everything going with preparations for Going Up?

Fantastic. The script was just published online—newyorktheatre.com—people are reading it, plenty of great responses. I have a lot of fans here in New York, and I would love to have that same fan base in Dublin, but it’s my second time at the festival this year, so we’ll see.

So you came to the festival last year, and that was also with Mark Pollard [director], yes?

Yes, last year was my first time at the festival, and Mark was my director. What I love most about this festival is the international aspect. Mark’s originally from Dublin, now lives in London. I’m also working with Gillian Tam for the second time who’s from Singapore; she’s our lighting designer and stage manager. Judi Uhuegbu, who’s our PR person, is originally from Nigeria. My actor Jonathan Chambers was born in Jamaica and grew up in Canada, and my other actor Andrew Fettes is from London. It’s really exciting, getting all these people united together in a festival for one week.

How did you gather all these people?

Well I had a play called Bitten which was the only American finalist for the Kenneth Branagh Award at the Windsor Fringe Festival, and it’s set in an Irish Pub in Queens. I actually didn’t know anything about this festival, but someone who came to see the show suggested to me that I submit it to the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival—one of the characters is gay. So I submitted it and it was accepted. I really wanted to work with English and Irish actors because it would be much cheaper given all the strict rules with American Equity actors, so Brian Merriman [festival director] recommended Mark Pollard who had directed at the festival many times. So Mark read my play, liked it, and we really hit it off when we met. He directed my short, Bitten, last year, and it was a huge success, so I decided that the next time around I wanted to do something longer. But I knew I could only do an hour because I’ve been to the Edinburgh Fringe and I know Dublin; people want to get to the pubs. You can’t do a long play, and people like comedies! And my play does touch on serious topics—bullying, homophobia, divorce—but I really feel that hammering people over the head is not the best way to get them to think about something, so I do it through comedy.

And how has the creative process been with this particular show?

Well it was, in part, inspired by Hurricane Sandy which hit the East coast a few years ago; a lot of people were actually stuck in elevators. I had also taken a conflict-resolution class, and the main thing with conflict-resolution is to put two people in a room with opposing views and not let them leave for an hour. So I thought, what if I had a play about two people with opposing views, one who’s a blue-collar, homophobic car-salesman, and the other, a gay transvestite. In terms of the process, a lot of times I work from setting. I get a setting and the characters come to me.

So you seem to enjoy a lot of aspects of Irish culture, or at least Irish-American culture. Is that a big part of your identity?

Well, it’s funny… I’m Jewish! Originally from New York, but my husband’s family is from Sligo, and I’ve been to Dublin about seven or eight times, just there in January, actually. I love Dublin! I’m part of the League of Professional Theatre Women, part of their international group. So we went over to Dublin, met a couple people from the Abbey Theatre, and I know Gina Costigan, an Irish actor I’m working with over here, whose father John Costigan ran the Gaiety Theatre, I believe, and her mother is Marie McDermott who’s a very well-known actress in Dublin. And I’m very active in the Irish Arts Centre, and I did a workshop there with an Irish playwright named Deirdre Kinahan who I think is one of the best writers writing right now. So it’s funny because I feel very immersed in Ireland, and I love Dublin, possibly my favorite city. Irish people are very warm and welcoming.

So you said you often use comedy to examine larger issues. Are you drawing on personal experience to examine these issues, or the experiences of others close to you?

Definitely from personal experience. There’s reference to a gay doctor who was beaten up in Central Park and is now blind in one eye—that was a story in the news. There’s also a reference to another story in the transvestite character in my play. The character reveals that he used to be a teacher, but he was falsely accused of molesting a child which blacklisted and ruined him, but he still really misses teaching. And the other character, Jack, the car-salesman, his marriage is dissolving, and that’s a reference to a friend of mine who’s wife left him for her personal trainer. So it sounds funny, there’s humour in there, but he’s heartbroken. And Going Up refers to a lot of things. The elevator is not going up, and poor Jack actually has problems with impotence, so that’s not going up either. But it’s this stranger out of nowhere who he initially doesn’t like that brings up his self-esteem. So that is actually going up. And there’s dancing, singing, yoga, even, all in an elevator, all in 50 minutes.

And has the show gone up before this festival?

Hasn’t been produced in New York yet, but I am hoping to bring it back once it’s done at the Dublin Gay Theatre Festival.

And do you think you’d take it to the Edinburgh Fringe?

No. I love the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival, but Edinburgh Fringe is 3,000 shows, standing in the rain, flyering for hours, and hoping eight people will show up. My friend calls it the Mt. Everest of theatre festivals. And I brought a drama there which was a mistake because people want to see comedy!

So I’m sure you know about the Dublin festival’s timing this year just before the upcoming Marriage Equality referendum. Marriage Equality has been teaming up with a number of theatrical productions this year leading up to the vote. How do you feel about the role of theatre in big issues like this?

I think it’s absolutely essential that theatre be for social change; that’s why I write plays. I have a play called I Know What Boys Want which is about cyber bullying, particularly about teenagers who are exposed on the internet and commit suicide. And when we did this, we would always have a talk-back, and you’d hear these stories from the audience, from teenagers and parents. I believe theatre can cause social change in a way that film cannot. I used to be a teacher, so I’m a big person for education after our plays. This is why I write theatre. I also used to be a novelist, and still am, but I don’t feel it causes the same kind of social change that theatre can.

So while you were working on novels, was theatre always a part of your life?

Well it’s interesting. I loved theatre in college, but I also wrote fiction, and when I graduated, my adviser really steered me away from theatre because she thought the world of publishing was a bit more…I’m going to use the word ‘respectable’ here, even though it sounds ridiculous. I wrote a novel, had a collection of short stories, but I really missed theatre. So when my daughter went to university, I just decided to write a play and see what happens, and five years later, I have lots of plays and productions to my name! I was actually just in a gun-control festival which is lately a huge issue here in the states.

And how did that festival go?

It was fascinating. I’m personally anti-gun, as is my whole family, but very intelligent people I knew would come and argue the issue with me, saying, ‘If you were a woman living alone in the middle of nowhere, are you saying you wouldn’t want a gun?’ And then there’s the argument that it’s not the gun’s fault. It’s a very divided issue, and the problem is that it’s in the US Constitution. So in terms of social change, I really found that the most challenging, convincing people why we need gun control, and that surprised me and upset me a lot.

And what kind of piece did you write for something like that?

Well I wrote a piece for a teenage boy called Before. The boy’s a normal kid, high-school football player, has a girlfriend, but the girlfriend ends up cheating on him with his brother. So his best friend gives him a gun. And in the piece, the gun kind of takes over; the kid really struggles with the gun. There’s a climactic scene where he sees the girlfriend, and he has the gun, and he knows he’s in power, and she falls on her feet weeping. Then he decides not to shoot her, but he doesn’t get rid of the gun, instead he puts it in a shoe box. So the show ends on an ambiguous note. I would love to bring that play over to Dublin, and I wanted to bring it to Edinburgh, but people told me it was too American.

The reason I ask is because you said you enjoy writing comedy, but for something like that, comedy might be tough.

Oh no, that definitely wasn’t a comedy! I mean, it had funny bits in it, because like I said, you can’t clobber your audience over the head, but it really made you think, just like the cyber-bullying play was supposed to make you think about how what you put on the internet can actually kill someone.

When you use theatre as an educational piece, do you prefer comedy to inform or do you lean more toward drama?

Well I definitely lean more toward drama, but I know this festival, and I knew that I needed comedy. I saw a lot of the plays last year, there was a lot of drama, so I wanted to do something fun and uplifting, something where people could have a good time in 50 minutes and talk about it afterward.

Going Up premieres at the 12th Annual International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival in the Teacher’s Club, 36, Parnell Square West, Dublin 1, May 4-9.