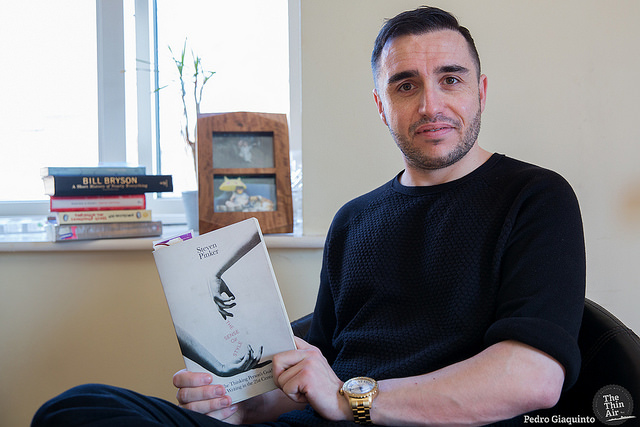

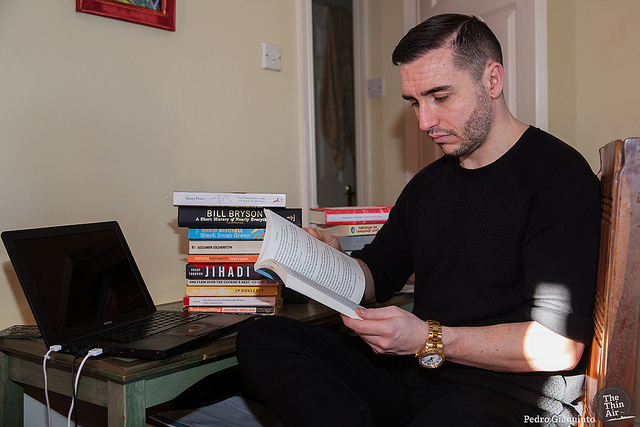

In this installment of Bookmark, we chat to Dublin author Frankie Gaffney about the books that have made the biggest impression on his life thus far. Photos by Pedro Giaquinto.

I’ve split my list into fiction and non-fiction. Non-fiction tends to get neglected, but it influences my writing every bit as much as fiction.

Non-Fiction

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson

This book gently and briefly explains what’s currently known about the universe: the very basics of the cosmos, our planet, and the life that inhabits it. For some reason they don’t really teach you the broad strokes of this stuff at school, which makes this essential reading.

Guns, Germs & Steel by Jared Diamond

A history of human-kind in one volume, Guns, Germs & Steel traces our journey from wild primate ancestors, to tribal hunter gatherers, to slave owning city-states, through feudalism, colonialism and capitalism. This book is the perfect antidote to rascist narratives of human evolution, but also a concise exposition on the emergence of those things which define us as human beings – in particular agriculture and language.

The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker

This should be the first book on the syllabus of every English literature or creative writing course. Ultimately, the medium writers work with is language. The Language Instinct explains clearly and precisely what language actually is, and how it works, from a scientific, empirical perspective. It’s packed to bursting with indisputable, hard-won hard facts about language. Pinker somehow manages to remain interesting (not to mention witty), throughout. Anyone who professes the remotest concern with words (spoken or written) should be falling over themselves to get at knowledge like this. Read it. Now.

The God Delusion by Richard Dawkins

There seems to be a trend (among the Left in particular for some unfathomable reason) to scoff at Dawkins’ atheism for its directness and simplicity – though I can’t understand why. When I was a child I was told repeatedly, by people in authority, that there literally was “a man in the sky” who would listen to me if I spoke to him, and who would grant or refuse requests at his discretion. This book dispelled me of that delusion, and in a few days relieved me of many of the burdens that came with 12 years of Catholic religious indoctrination at school. Whatever your opinion of Dawkins, this book was necessary – even if only to slightly redress the balance.

The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker

The one book I wish I’d read before I’d started writing. It’s aimed more towards journalism and academic writing than fiction, but much of the advice on clarity, brevity, and tone, is universally applicable. Unlike most commentators on language, Steven Pinker is truly qualified to offer prescriptive pronouncements on written English. He is a linguist, cognitive psychologist, not to mention a master of style in his own right. This is the definitive style-guide for the 21st Century.

Fiction

Borstal Boy by Brendan Behan

This literary memoir straddles fiction and non-fiction – though I certainly doubt Behan ever let the truth get in the way of a good story. I love this book for its rare quality among our ‘national’ narratives: irreverence. Behan was an unrepentant IRA man, but his disdain for authority is directed at Irish republicanism as often as British imperialism. Indeed Borstal Boy is remarkable as a prison narrative, in that it’s also a love letter to the country he was gaoled in. Behan learns to appreciate Rugby, benefits from the English ideal of gentlemanly fairness, realises his natural affinity with city lads from Birmingham and London – and falls in love with a sailor-boy from the British Navy. A poignant working-class masterpiece, packed with Behan’s trademark wit and banter.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon

This is a book I’d happily recommend to absolutely anyone. I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed reading a book so much, or found a book so easy to read.Typographic experiments and mages integrated with text, exploiting the medium of print to the fullest. This book shows that readability and literary innovation don’t have to be mutually exclusive – a lesson that many authors with high artistic pretensions would do well to learn.

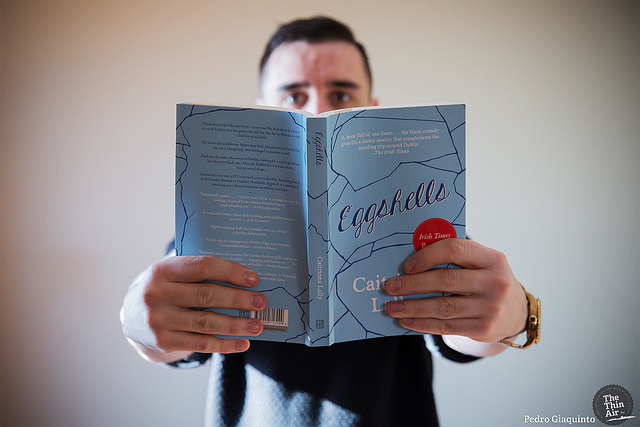

Eggshells by Caitriona Lally

I thought it might be appropriate to end on the book I’m currently reading – so I haven’t finished this one yet, but it is a gem. Weird, sumptuous, calmly confident – and absolutely bursting with original quirky ideas. Eggshells is a unique topsy-turvy book that deserves to find its place in the canon of great Dublin literature. Joyce would have loved it.

Kalilah & Dimnah translated by Hassan Tehranchian, illustrated by Annatole Ur

This is a collection of ancient fables translated from Persian. The various stories are framed within a meta-narrative: two jackals counsel each other with a dialogue of competing parables. The collection originates in India (as the Panchatantra), but the stories have been found in over 200 languages, in a geographic range from Java to Iceland.

My Ma got me this lovely illustrated version and read the stories to me when I was a kid. Like all folktales for children, darkness and terror loom throughout. Wily canines Kalilah and Dimnah rarely offer a happy ending. But firmly in the Eastern tradition, they do teach how insatiable desires lead towards tragedy, and offer sage warnings about the ills of avarice and the dangers of treachery. I found the lessons contained within had a mercantile bent, more firmly applicable to city life than the rustic tales of Aesop or the brothers Grimm.

Atomised by Michel Houllebecq

A stark and shocking portrayal of the atomisation of Western society, and the consequences (particularly for men) of the collapse of institutions like the Church, the community, and the family.

In Ulysses, Joyce painted the most complete portrait to date of the human condition. In Atomised, Houellebecq exceeds even Joyce’s legendary ambition. Echoing Marx’s maxim that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it,” Houellebecq sets forth an ethics that aims actually to bring about the end of the human condition itself. A disturbingly prescient novel considering recent developments in the programming of human DNA.