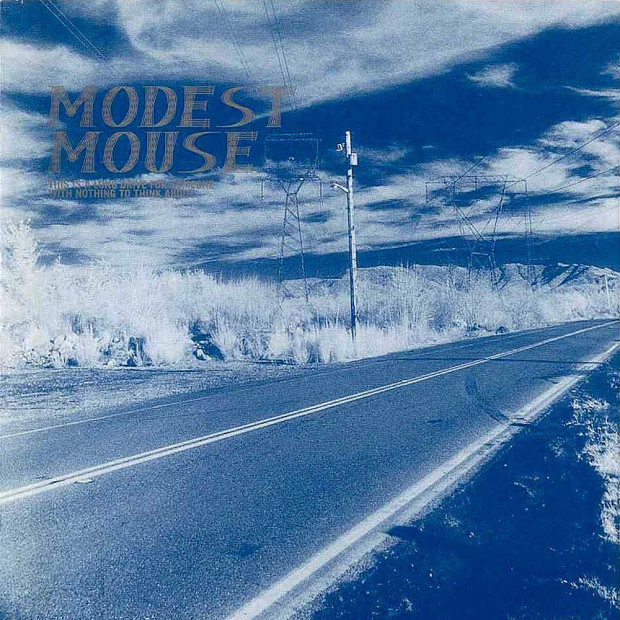

What do you think of when you hear the phrase ‘driving music’? As musical notions go, it’s one that usually comes with a specific set of aesthetic criteria. Upbeat tempos, big choruses, maybe the occasional indulgent guitar solo. This Is A Long Drive For Someone With Nothing To Think About, the debut of Issaquah indie rockers Modest Mouse, turned twenty last Saturday. While directly referencing both a long journey and a clear mind, if anything this album is the protracted, pensive inverse of canonical ‘driving music’ – ‘Don’t Stop Me Now’ with a dicey hangover. Modest Mouse emerged in the early nineties as part of a curious cadre of Northwestern American indie-punk bands like Lync and Heavens to Betsy (who were an early incarnation of Riot Grrrl nobility Sleater Kinney). Raised on a mix of Seattle post-hardcore & the more considered songcraft of bands like Built to Spill, they forged a sound in the early years of their career that still sounds utterly unique, even two decades later. In the wake of their pathologically average recent effort, Strangers to Ourselves, it’s worth looking back at their debut; what you happen to find is an almost entirely different band – callow yet surprisingly self-assured.

Their creative locus is guitarist, vocalist and songwriter Isaac Brock, bolstered at the time of recording by Jeremiah Green on drums and Eric Judy on bass. Brock’s songwriting has this spooky ability to synthesise a mainstream-alt-rock grasp of melody with a punk/garage acumen – meandering guitar riffs and driving basslines slide along on a bed of lethargic percussion, frequently interrupted by flashes of noise & discord that feel completely natural. It’s a sound they would go on to sharpen, then gloriously expand (On Lonesome Crowded West and The Moon & Antarctica, respectively), though it’s here that you’re confronted with that sound in its skeletal form, before the sinew and flesh of those later, arguably superior efforts. As the somewhat cumbersome title suggests, ‘travel’ is an idea that courses through the record, but thematically it’s more about a sense of boundless physical space generating an intense mental claustrophobia. If you’re feeling indulgent, you could even go so far as to view it as a postmodern articulation of the American travel narrative – motion as the illusion of progress – but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

This is a record of contradictions; anarchic and scrupulous, manic yet precise. The group display a competent understanding of dynamics, yet make everything seem almost slapdash in execution. The arrangements frequently come across as sparse – brittle, even. Brock’s voice, which resembles a dustbowl Black Francis with a lisp, is in exhibition mode for the majority of the album – here it’s an anguished lullaby (‘Talking Shit About A Pretty Sunset’), there it reaches a pitch that can only be described as a bark (‘Lounge’). His caterwauling achieves an oddly satisfying harmony with both his mercurial guitar playing and the robust energy of his bandmates – an ideal setup for the genre patchwork project the album ends up becoming. Jeremiah Green produces some of the best drumming you’re likely to find on a guitar album from this period – exuberant and animated in a way that lend the songs some real heft; there’s a genuine thwack to the snare & a chill to the cymbals. Likewise, Eric Judy’s basslines fluctuate between a tumbleweed amble and a dutiful yet nervous bounce. Both do well to avoid being submerged by Brock’s urgency. There’s a thick vein of lyrical and instrumental anxiety running through here – the frequent repetition makes the sudden yelps & tremors in Brock’s voice appear spontaneous, like someone drifting into a daydream while driving, only to be jolted back into consciousness by something on the horizon. It’s a constant instrumental balancing act between the dreamlike & the obscene – one of the most weirdly evocative moments on the album comes five seconds into ‘Custom Concern’, during the several nanoseconds of white noise that accompany Brock’s fingers sliding between frets.

It’s through this balancing act that the band’s subversive approach to song structure makes itself known. Elliptical riffs, like thought loops, drift in and out of focus. It’s easy to forget you’re listening. Oftentimes the extraneous elements will fall away, allowing Brock’s guitar to follow an almost Brownian motion that’s subtly structured despite its outwardly freeform appearance. Conventional beginnings end up transmuting into labyrinthine guitar stints, replete with otherworldly string bends, that seem like almost perfect aural encapsulations of anxiety in transit. ‘Beach Side Property’ starts out ordinarily enough with its boilerplate chord chug, before an anxious guitar stab anticipates Brock literally howling over the instruments, which is followed by a vaguely sinister interval where everything sounds magnified by sheer virtue of the manic arrangements that preceded it. Moments like this echo the start/stop, whisper/scream kinetics codified five years earlier by Slint’s Spiderland. While I’d like to argue that the middle of this album (which is essentially several variations of the same blueprint) is some sort of artistic decision on the band’s part – maybe a mirror of the monotony of long journeys through anonymous countryside – the reality is that some of it is genuinely just filler; compelling, dizzying filler, but filler nonetheless. Having said that, the playing is surprisingly confident & tight for a band that, at the time, still didn’t really know what sonic direction they wanted to take. Any experimentation is subtle; now and again some dissonant static will invade certain songs, as though someone were tuning the dial on an old car radio mid-track.

While superficially operating within the barren physical spaces suggested by the music, it’s through Brock’s lyrics that an interior landscape, the one the album truly inhabits, is projected. It’s a schizophrenic process made tenable by Brock’s gnomic lyricism, which see-saws between the pseudoprofundity of bathroom graffiti (“We kiss on the mouth but still cough down our sleeves”) and something approaching flannel-coated Zen (“I’m not sure who I am but I know who I’ve been”). It’s a wry brand of confessional songwriting, one perfectly in sync with the ironic slacker zeitgeist (think Pavement, Smashing Pumpkins, Sonic Youth, etc.) of its time. Track titles like ‘Talking Shit About A Pretty Sunset’ are enough to give you a sense of the tone of the record. While not exactly sounding fresh today, the album does have a startling aesthetic that’s worth re-visiting. What you’ll find is a masterclass in wrenching the most out of decidedly lo-fi circumstances. It’s a record that won’t rust – a hypnotic fever dream of Americana played out in slow motion. Eoin Lynskey