Steven Maybury’s latest shows, Anicca and Dukkha, highlight an emerging artist whose practice is evolving and diversifying in the most interesting of fashions. In this edition of Primer Aidan Kelly Murphy sits down to chat about his work, influences and plans for the future.

Did you always have an interest in the arts and want to pursue a life as an artist, or was it something that evolved naturally?

It’s a strange one because I grew up with my father being a picture framer so I was always surrounded by artworks. I used to work with him cleaning the artists’ studios that he was inhabiting. I did discuss making art in school but it wasn’t really until I left school and went traveling. From there I realised it was an incredible way to see the world, an incredible way to understand the world.

Did you have a practice at that stage or was it something you found yourself casually dabbling in?

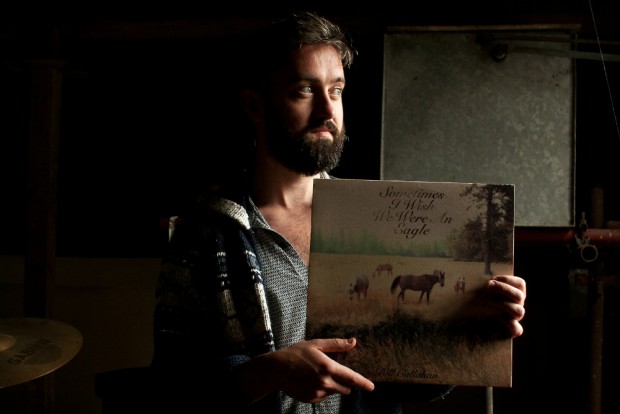

Just dabbling, I didn’t really know exactly what I was doing. Drawing pictures was great fun, making paintings. Being inspired by lots of different things at the time, like music album covers, the bottoms of skateboards; a lot of stuff I was interested in was very graphic based. When I went travelling I realised that it was a great way to see and remember the world was by recording it. I then learnt how to use a camera and it just fed my creativity, and gave me an avenue to explore different things. I also had a lot of friends who were interested in and were creating art, so I kind of piggy-backed on what they were looking at, until eventually I fell into it myself. There was definitely a frustration there when you were younger as well, primarily because I didn’t know what I wanted to do when I was a child growing up. Art always seemed to have a level of accessibility, something that held my attention and was fun but was also engaging and very broad – it could be whatever you wanted it to be.

What avenues in life inspire you to create work? Are you a go-out and search or wait for something to come to you?

To be honest it’s a combination of things. My thinking and ideas evolve from interactions with world, from reading to cinema or music. A lot of the work I create comes from things that I come across – I call it my stumble-upon approach. Often they’re discarded debris or stuff that isn’t wanted, things that have been outdated essentially. I find particular beauty inside these as they allow me to comment further with what I want to create. In terms of inspiration it can come from anywhere really. A lot of stuff I’ve been inspired by is very natural, in terms of being outdoors, exploring, traveling and very much of that mindset.

Do you feel that this relaxed approach transfers over to the materials you’ve selected to create your work, or do you find yourself more selective with the initial choice?

No, it’s generally one of those things that’s based on a mindset or an observation. An observational stance in the sense that I find a lot of the stuff that I work with from reoccurring patterns, for example I made a series of work with combs and rulers. Theses were found, expired materials that didn’t have a function anymore as part of their design had been compromised. I found myself continuously finding these to the point that I started collecting these – so in a sense these things happen consciously, but also not so consciously.

For any artist their practice is crucial in their life, do you feel this approach of collecting and cataloging is crucial to you in a way that transcends the work that you create and is this something that you need to do?

There is an obsessive nature there but the obsessive nature comes more from a curiosity. There’s a want to understand things but there is also a knowing that I’ll never understand things and this ‘want’ allows me to gravitate towards theories or ideas that I have about the world and different things. It’s an avenue for me to start thinking about things. A lot of the work I create can be seen as incredibly repetitive and sometimes obsessive but at the same time it’s doesn’t seem like that to me.

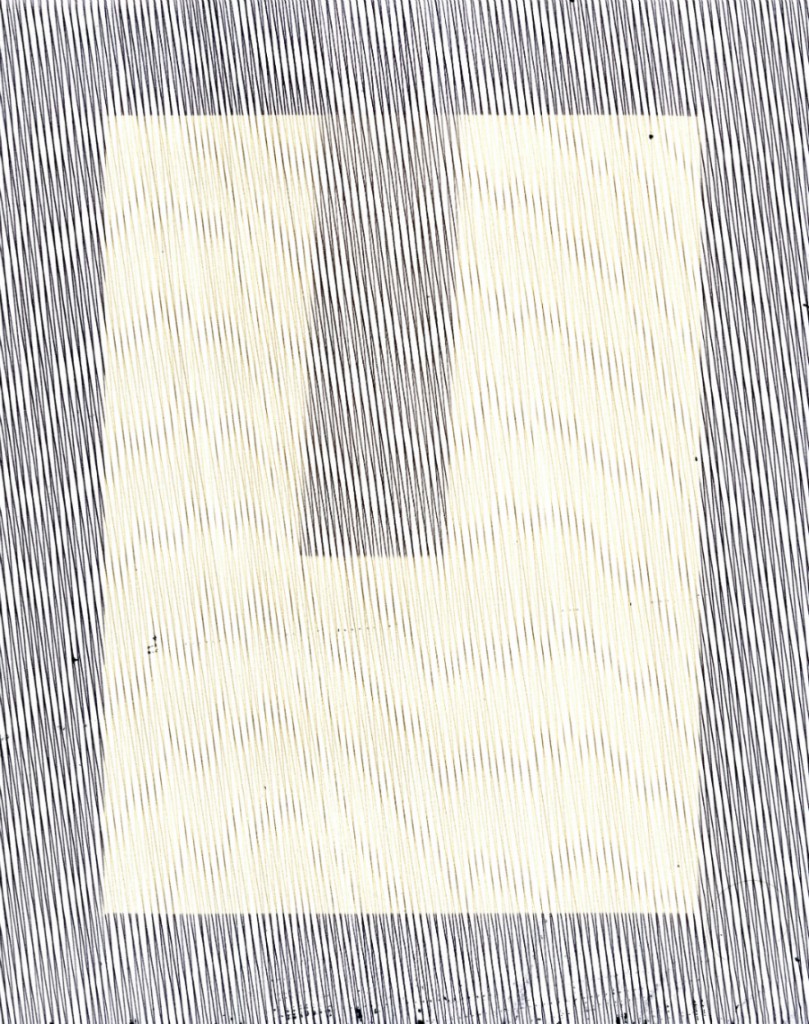

Just touching on that repetitive nature, you’re known for your distinctive lines drawings in both pencil and pen, retrospectively looking back at this was it something that was born out of the evolution of your practice over or was it more of a direct decision?

No, it’s definitely something that I found, when I was studying painting in Sligo I was taught different aspects of painting and was introduced to different aspects of the art world. It’s funny because there I was creating very different work until I transferred to Dublin. Once in Dublin I started creating these lines drawings out a response of leaving the other place. It was more of a control, more contained but also more free in another aspect and more raw. It was definitely an evolution of trying to find things. I think there was also a realisation that I had had a support network when I was in Sligo and when I came to Dublin I didn’t so I was left to figure things out by myself.

So you were able to log those 10,000 hours in your own practice?

Essentially yes, that’s exactly what it was. I realised very earlier that this was going to be my job. I mean a lot of people were doing degrees in marketing or accountancy, stuff that you have a job when you come out and if you want to make this work you have to be very attentive. So I ended up getting a studio outside of college while I was still in college so that when I was finished my classes I could go to it. I would work there, developing new ideas and have works there that were being created but not seen in college. I could leave things for days, weeks untouched essentially.

On the subject of a studio you’re currently in Ormond Quay Studios in town. Are you more of a studio artist that creates and develops their ideas in their own space or more of an artists that formulates and idea and then brings it back to their studio to work on? Is a studio a creative or a work environment for you?

Both! A studio is also somewhere where I store things.

In every aspect of the word? Would you drop something at the door and pick it up when you return?

No, definitely not. What I realised very earlier on, and which is something about the art world that I still love, is it doesn’t work like that. It’s not a 9-5, you don’t start making art at 9 in the morning and finish at 5. It doesn’t stop essentially, at any point you’re thinking, you’re writing, you’re creating a dialogue or continuing a dialogue with yourself. I’d like to think that are particular modes that I go into, like when I go into production mode and am making things, particular things would can only be made in a studio. The majority of my staring at walls changes in environments, it could be staring at into an empty pint glass, it could be staring out to the ocean it could anytime, mindlessly watching M*A*S*H it could be anything.

Speaking of studio spaces, last year you had a six month residency in the RHA, how much did that experience of being the RHA and the change of environment and space have on your practice?

That’s actually a really interesting question, as it comes down to time and time management as well. The studio that I had in the RHA for six months was a residency and I was lucky enough to go in there with ideas. I was at a time when I wanted to start creating work from ideas that had been growing and mustering for a little while but were hampered by limitations in terms of the dialogue between works or creating works beside each other. So for a residency to have such a huge space to create works in was incredible. That said, I also realised that now that I had to do this, and I found that in order to open up other doors, you cancel out other things in your life. You realise this is your time and that you’re going to make this work in the space the residency offers. It gives you an identifiable time period where you can go into production mode. Some artists thinking totally different and use it for thinking or researching. I generally need space to make work, and space is something that is very valuable.

When you were in the RHA you put on three shows, can you talk us through how they came about?

They all ran concurrently and were initially supposed to be one exhibition. That’s where the playfulness of having such a larger studio came into affect, feeling like a kid in a candy store with all this space where you’re making all this work compulsively. Dedicating a lot of time to developing ideas and been given the resources to do so. I had several large works that were being made in one small area and I soon realised that maybe they aren’t meant to be shown together, maybe they need to be shown separately. So those three shows ended up becoming three sister shows that ran concurrently. They overlapped each other with each on opening a week after each other, creating a dialogue in a city as well which is an interesting aspect to look at art exhibitions. I mean one aspect of looking at a body of work is given in one exhibition while that’s being challenged by another, while together in another and created singularly.

Your show Anicca opened in The Library Project in Temple Bar in May, a progression of your earlier work with a new approach through different mediums. Can you talk us through how the show came together?

Anicca is a progression in my own practice and thinking. Before those three shows in the RHA had finished I had begun the idea for this show Anicca. It didn’t have the name Anicca at the time but the works were processing in my mind. The idea that things could expire, that things have a temporary and impermanent nature was resonating with my own practice and my obsession with drawing and fault lines, the attempt to find beauty in the ripples and faults that are in material or matter. I came across an exhibition in the Douglas Hyde Gallery called ‘Dukkha’, a pali word meaning the stresses and strains and anxieties of life. It’s a Buddhist doctrine, that helps you to understand and become content with the fact that life’s a bitch. I was very taken aback by this exhibition, and I found some of the works very much in conflict with each other and this only added to the sense of the exhibition. That exhibition stuck in my mind and the began to research into it the content of behind it and I came across more of these doctrines that are adopted by Buddhism and one was the term Anicca. Anicca meaning the impermanence, the inconstant idea, the temporariness of life and again coming to terms with that apparently you’re meant to feel a lot more content and fulfilled in your life with the fact that you’ve accepted that things don’t last forever. That was the beginning of the research in terms of literary studies behind this exhibition. The making of the works themselves evolved from the drawings that I was doing for the trio of exhibitions and they fell into similar aesthetics. I began to recognise other areas of destruction, other areas of temporary relationships which lead me to look at my own rituals and my own obsessions. One of which was based on repetitions that were similar to my drawings, and this was skateboarding. Skateboards are one of the materials that I work with in this exhibition, there is an analysis and archiving of them and the ritual behind them. These things come spick and span, spruced with a really nice graphic and the last thing you want to do is destroy it but the only way you can skateboard is by essentially destroying it. The marks that came with this destruction choreographed and recorded very particular moments. With this in mind I started skateboarding certain decks that I was buying and performing single tricks on them so I would literally be mapping my own working with one trick; my obsessive nature wanted to complete something through repetition.

Almost like a scientific approach, a stress testing of the object and then document it each time to see if it will eventually break or perhaps form something new?

That’s exactly it, that’s a good way of putting it. It’s the same with the drawings as well because there is a lot of stamina in terms of materials. The materials aren’t as contested as they were in previous drawings, these are much smaller, but at the same time they’re showing more of an identity of the objects and the reality of their destruction. In Anicca there are a series of 17 drawings, 3 skateboards and 3 reproductions of the scratch and scrapes on the skateboards blown up quite large through large format printing. These are expressionistic, almost painter like prints. The skateboards put onto spits like a pig, rotating to give the idea of constant as well. So there are a number of different elements – sculpture, photographic and framed drawings – and it’s the first exhibition that I’ve ever had that where the entire show is framed, which is exciting. Exciting in the sense that it’s scrutinising the idea of presentation and archiving, especially in the art world and our obsessive natures of doing things and wanting everything to last forever essentially.

Once this idea had come together, from a logistical point of view what support structures did you have to realise the show and create the works?

It’s a very important question because when you have these ideas in your mind it can be very strenuous in terms of financing them. There is always a huge amount of saving and in turn a huge commitment to your own financial situation in order to produce something. I found that with this show I had very particular ideas and visions for what I wanted it to do, so I knew I needed to get some form of support in order to finish this exhibition and have the particular attentions to detail that I wanted. I was lucky enough to become one the Artists Support Scheme Award winners with the Fingal County Council. They provided me with a bursary in order to support and create this particular project, and also to give the attention to detail that I wanted to create. I don’t think it would have been possible to make without that level of support, and for that I’m eternally gratefully.

Prior to Anicca opening you curated a photography show entitled Phototropism in the same space, how did that affect your own practice?

The Library Project, just to give a quick introduction to it, is a photographic space in Dublin that consists of a library, a bookstore and a gallery space that deals with thinkings behind contemporary photography but pushing it that little bit further. It’s also a space that I’ve been working with for the last four years and in its the current location for three years, where I’ve helped installing, de-installing and being a technical support for the gallery. So I feel that I know that space incredibly well and I feel somewhat cheeky exhibiting in the space where I work but at the same time I’m doing because I do know it so well. The exhibition Phototropism was constructed by myself and co-curator Ángel Luis González Fernández and it was a response to the space and this is the first exhibition that we were able to curate, develop and execute ourselves where we used the entire building rather than just the gallery space and to extend the function of what a gallery or an exhibition can be or do.

Photography is obviously a big part of your practice then.

Photography is a huge part of my inspiration and how I channel things in the world. I have used a lot of photographic industries and methods in creating works in previous shows, as well in terms displaying works through projections and animations. This particular show uses for the first time photographs essentially, in terms of presenting a replication of something. I’m archiving and detailing elements of skateboarding and blowing them up huge to become almost abstract expressionist paintings. They also play as a backdrop as other works are hung on top of them. They’re printed almost like posters and pasted onto a wall so they have this conflict as they’re a photograph, but they’re not a serious photograph. They’re a photograph that essentially has to be ripped off a wall at the end of the show. The drawings in the show are activated by light, they’ve been exposed to light for long periods of time to create fades in the drawings themselves, they almost mimic cameras in how the work in that sense.

What you’re saying there loops back to what we discussed earlier when you were finding your feet in the art world and photography provided the backdrop to your life. In this show the photographs provide a backdrop to the drawings, providing an almost ‘full circle’ aspect to the show. Do you anticipate a very personal extraction by the audience?

Yeah, it’s something that I think is a crucial element to this work, in fact I’d even go as bold as to say it’s a personal ritual that I use. To bring it back to your ‘full circle comment’, that’s a very interesting aspect to think about because essentially it is. I use cameras as a tool but also as a way of life – a way of thinking through life. I question what is a photograph and what can be a seen as photograph and what a photograph can do. The works in Anicca don’t necessarily look like photographs or act like photographs but they are certainly still photographs which is an interesting dialogue. One that I’m only bringing to start to figure out but one that is a really engaging platform to explore.

You show Dukkha recently ran in Belfast, can you talk us through it?

Dukkha opened in Belfast on June 3rd in Platform Arts. It wasn’t a sister show as such but certainly a show that is related to Anicca. Dukkha was the name of the exhibition I discussed earlier in the Douglas Hyde Gallery, and my own three shows that were created in the RHA coincided with when this show was on. It wasn’t not a homage exactly, in some ways it is in some ways it more of a reaction to the things that I was working on at the time. Dukkha was a choreographed editing of those three shows back into one. I wanted to create a more solid idea, a more solid output.

Did you use the early blueprint of when it was originally one show, and try to reverse the process in order to revert it back into one or did you use a separate process to return it to one show?

The idea of those shows became very big, very quickly and developed into three exhibitions. When I was in the mindset of these Buddhist doctrines during the development of Anicca, I realised the there was a core that I was missing. I felt I hadn’t resolved this so I wanted to go back and essentially figure it out a little bit more. The return to creating artwork and the return to thinking I find is really important. Constantly in our day to day lives or socially we look back in history and we use that. In art practice we look at art history all the time; we also compare new works to old works and we have this constant dialogue we’re we use our archives. It’s very important for an artist to do this as well. This it’s not a show that is being made but a show that has already been made and is edited. There have new works created to help gel particulars together but in the sense of even how the show is going to be displayed they’re going to become radically different things. I think it’s evolved into what my practice has evolved into, it’s catching up to where my practice is. I was able to refresh and look back and not create something new but something I wanted to do back then.

Did you find the end result, was it a massive departure from the original creation point?

It’s a more concise point of view, while I don’t think I had the terminology or maybe the cunningness to evolve the show in exactly the way I wanted to, and that’s probably why it ended up as three exhibitions. I now feel that I can go back and more concisely get across the idea. I felt that I had created that work but it was on a different level of thinking and using different terminology, different languages, so by integrating that all together I feel that I’ve created the same dialogue but in a slightly different manner essentially.

What does the future hold?

I embark on a trip which takes me across the world. I’ve entered the Mongol Rally with a childhood friend and we embark on an adventure in a really shitty car that is totally not capable to the job at hand! We’re going to attempt to drive across the world going through Europe, Turkey, Iran, Turkmenistan, all the way through Kazakhstan to Mongolia and then onto Russia where we’ll fly home from there. It’s going to be six weeks of madness.

A return to the travels after school, fill the inspirational tank once more?

It’s funny that you say that, I travel a lot and I’m fortunate enough that the work I do allows me to travel a lot. But it’s funny you brought that up because it’s been a decade since I left, ten whole years. It could become a thing that I do every 10 years, and hopefully it does.

The first trip you have had one mode of documentation – photography – whereas now you have some many more. How are you going to document it this time?

There will be a lot of photographs taken and a lot of moments created but I think the main reasons I’m going is the interactions. I want to experience a lot of cultures and meet a lot of people. I’m not so keen on overly archiving of what I’m doing at each individual moment, I’m looking for to get an overall sense of what the trip was. I’m bringing cameras try to create more of an idea of what is happening rather than have severe repetitive documentation.

Keep up with Steven Maybury here