It’s something of an accepted cultural trope that sixties music was awash with recreational drug use. Acid, in particular, still holds a central place in many people’s conception of the sixties western counterculture as a socio-historical phenomenon, to the extent that anyone wishing to visually document the decade seems obligated to include a montage of marches, hirsute men and women looking a bit glazed, riots, Hendrix, more marches & Nixon – all set to the Rolling Stones’ ‘Gimme Shelter’. It’s one of those culturally reductive but semiotically useful ways of describing material history, albeit one that leads to sourceless pseudo-proverbs like “If you can remember the 60’s, you weren’t really there”.

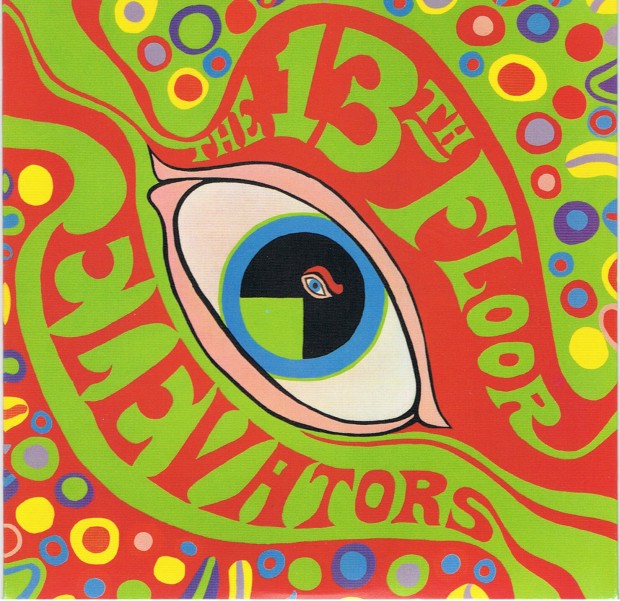

While there’s no denying that many musicians of this era (or any era, come to think of it) used drugs as a creative stimulus, ‘psychedelia’ has by now almost become rhetorical shorthand for a certain stratum of 60’s popular music. If the garish compilation covers are anything to go by, this was a time of bright lights and primary colours – perhaps it’s no coincidence that this was the time colour TV first made its appearance. But while during this period the Beatles were writing eccentric nursery rhymes about celestial women named Lucy, and Dylan was imploring a man with a tambourine for ‘one more tune’, a band called the 13th Floor Elevators were forging some of the first truly ‘psychedelic’ music – an earnest attempt to aurally capture the experience of an expanding consciousness. For better or worse, they broke on through to the other side, and then went house-hunting.

Formed in Austin, Texas in 1965, the Elevators are often credited with the first descriptive use of the term ‘psychedelic’ in popular music (though this is more apocryphal than anything, such a broad term that was so central to a certain zeitgeist would be near-impossible to trace the true etymology of). Marshalled together by lyricist, acid monk and electric jug player Tommy Hall, they originally consisted of guitarist Stacy Sutherland, drummer John Ike Walton, bassist Ronnie Leatherman and vocalist Roky Erickson. It’s somewhat remarkable (or maybe understandable?) that such a fiercely unique band managed to emerge from Texas – a place that at the time was in the quiet grip of a Christian social hegemony & some of the most regressive drug laws of any state in America. While the idea of ‘sixties psychedelia’ is sort of an umbrella term that can apply to a vast range of bands that were active at this time – from the impenetrable geometries of Can’s Monster Movie to the elastic folk-pop of Love’s Forever Changes – the release of the Elevators’ debut, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (as succinct a title as can be imagined) in October of 1966 led to it becoming one of the founding texts of this most pliable of genres.

The opener, ‘You’re Gonna Miss Me’ (a holdover from Erickson’s previous band the Spades, here given a new, hallucinatory lease of life) is a rip-roaring track about alienated love, showcasing both Erickson’s mercurial vocal stylings and Sutherland’s growling guitar. This is quickly followed by ‘Roller Coaster’, with the hypnotic recurrence of its central riff conjuring some purgatorial fairground ride. What you find here is traditional rock arrangements, only drenched in a kaleidoscopic fug. What’s significant about the Elevators is that instead of integrating coded references to drug use as some sort of aesthetic feature, they were one of the first bands to adopt them as a fundamental component of their entire approach to recording. They turned this notion of lysergic mind expansion into a full-blown recording philosophy – the naive, naturally doomed idea that exposing new, previously concealed realities of the mind could somehow reveal new, previously concealed realities of sound. This optimism is probably best illustrated through the dialectically batshit manifesto they printed in the album’s sleeve notes – which was likely intended as some neo-Hegelian call to arms for radically new systems of assembling knowledge, but in reality reads like an endearingly nonsensical monologue from a catastrophically stoned friend.

Such chaotic soundscapes could easily have turned the album into an indulgent mess, but the group always had a firm understanding of songcraft. The occult shimmy of tracks like ‘Thru The Rhythm’ & ‘Reverberation’ are invigoratingly weird, as is the menacing crawl of ‘Kingdom of Heaven’, where Erickson’s insistent vocals slowly percolate through a grainy, spiralling guitar riff (and which was used to brilliant effect at the end of an episode of the first season of HBO miniseries True Detective). They could also be melodic – saccharine, even. On ‘Splash 1’, Erickson sings lines like “I’ve seen your face before, I’ve known you all my life” (supposedly written after he met Janis Joplin at a party) and “I’m home, to stay” that cleanse the otherwise foggy atmospherics. Somehow, these soupy setups never threaten to submerge the band’s dynamic – see the proto-garage spark of album closer ‘Tried To Hide’, which became a fixture of post-punk gods Television’s live sets. In fact, the Elevators’ frenzied chemistry came into its own when showcased as a unit. Purported to have liberally circulated doses of LSD to the crowd when playing in states where it was (at the time) still functionally legal, as a live band the Elevators were a wild electric Leviathan. The surviving bootlegs of these shows are a little harsh sonically speaking, yet exhibit an energy and intensity that’s still legendary. They would appear on stage off their heads on acid, playing fast and loud to the point where it must have been uncertain whether it would be the speakers or the synapses that would give out first.

One of the most enduring aspects of their sound is Tommy Hall’s idiosyncratic playing of the electric jug (a literal jug hooked up to a microphone), a thoroughly strange ingredient that’s found sprinkled all over the record. It floats, ghostlike, in and out of the songs – so that upon hearing it you tend to zero in and try to understand just what the hell that “dugadigadigadugadiga” noise is, before it melts off again into the background, so you wonder if maybe there’s something at fault with your earphones, or whether the sound was ever really there at all & perhaps you’re getting some vicarious buzz off the album’s unabashed madness. There’s something uncategorisable about the sound, something essentially psychedelic – the kind of sound they likely wanted to evoke the pallid paranoia and giddy uncertainty of a trip. It is the sort of thing that can really grate if you’re not into it, mind, and can be a bit of a deal-breaker for some listeners.

Such an uncompromising approach to recording and playing was always destined to burn out eventually – what goes up, etc. The group recorded one more album with the original lineup – the more experimental, earthy Easter Everywhere – before essentially disbanding and beginning their retreat into the fringes of rock mythology. Stacy Sutherland recorded one final album under the Elevators name (minus the Erickson/Hall axis) before he was tragically killed in a domestic incident in 1978. Roky Erickson was arrested for possession of a miniscule amount of marijuana in 1969; in lieu of prison he pleaded insanity, and grappled with mental, financial and legal difficulties for many years afterwards. John Ike Walton seems afflicted with a Baudrillardian curse, playing in an Elevators cover band that eventually came to be named after him. Tommy Hall, jug maestro and the strangest of a strange bunch, became a minor recluse. These days he looks like Alan Moore auditioning for the role of Doctor Who, toiling away on ‘The Design’ – his laudable attempt to fashion a ‘theory of everything’ through a synthesis of physics, philosophy, anarcho-mysticism, yoga and the work of visionary Romantic poet William Blake. His friends admit the theory currently doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Despite burning out relatively quickly, the Elevators have cast a long shadow. They featured on the Nuggets compilation, a colourful catalogue of the vibrant scene they helped shape. They were at the vanguard as psychedelic rock and garage rock were developing into discernible subgenres, and their chemical insanity would later influence the DNA of 80’s noise acts like the Butthole Surfers and Scratch Acid. They were in many ways the ultimate hippies, believing that the idea of consciously altering consciousness was the first step in some greater liberation of society; the only problem being that eventually they had to come back down. Eoin Lynskey