What if anything truly was possible? Anything at all, no matter how outlandish, unlikely or, depending on your own proclivities, morally wrong, was within your grasp. You could think of an object, place, person or talent, and it would be given to you, almost entirely free of charge, and you could use these things entirely as you saw fit. It is an intriguing if slightly worrying question, and one that leads on to other intriguing if slightly worrying questions, chief of which is the thorny philosophical debate over causality: do all actions have a reaction, and do all causes have consequences?

The answer, naturally, is a resounding “yes”. While it is tempting to believe that all possibilities are indeed possible without the inconvenience of guilt, we cannot live in this world or any other without making an impression on our immediate surroundings. Push over a glass, and it will spill its contents onto the floor. Eat too much chocolate, crisps and fizzy cola, and your health will begin to suffer. Commit a crime, and the police will come looking for you.

This construct is, intentionally or otherwise, at the heart of most videogames, which pretend to offer the player virtual worlds characterised by the mouth-watering promise of possibility. In these simulations, the player can commit all sorts of deeds, both benevolent and malicious, without any real-world consequence. It is the avatar, not the player, who is at fault, and he or she effectively ceases to exist after the console is powered down or switched off.

The most interesting titles toy with this conceit, and in doing so make playing them a riveting, at times uncomfortable experience. Arguably, the most notable of this subgenre is the Bioshock franchise, where each instalment has increasingly pushed back traditional parameters of notions of good and evil, cause and effect, and free will versus determinism. This may sound like no fun whatsoever: I want to shoot people and make buildings go bang, bang; I don’t need a lecture from someone who has read Philosophy For Dummies, thank you very much. However, one of the things that make all Bioshock games great is the way in which they combine lofty ideas with satisfying mechanics and clever level design. The melding of frenzied combat with a beguiling, deeply unsettling tone offers a gaming experience like no other. Don’t get me wrong: I like the wacky silliness of Rayman Legends or the brain-numbing theatrics of Gears Of War as much as the next emotionally stunted nerd, but Bioshock has a certain intangible quality that lingers in the mind long after playing.

All three games and all of their accompanying DLC are included in this re-mastered compendium, and together they offer a fascinating overview of how the developers have expanded and refined the series. It would be advisable to play them in the order of their release, if only to avoid spoilers for a storyline that is rooted in intrigue and the unknown. First up is the original Bioshock, in which our everyman protagonist “Jack” (I am Jack’s encroaching sense of paranoia) investigates the vast submarine city Rapture – an Art Deco Atlantis that was built as a testament to the belief that the impossible is possible. There is no doubt about it: taking the bathysphere to the bottom of the Atlantic and seeing the sprawling city with its neon speakeasies, ballrooms, apartments, winding glass tunnels and stone statues remains one of the most breathtaking moments in the history of gaming. This metropolis is just so odd that it is easy to forget that you are playing a videogame; you might instead believe that you have slipped between the velvety blue folds of a dream.

This feeling of awe, however, does not last. Rapture, previously envisioned as a modern utopia, a place where all pleasures are catered for and none are subject to scorn, has descended into anarchy: the inhabitants, driven mad by cabin fever and bootlegged alcohol, have mutilated each other and themselves; each room is a midden of ransacked suitcases, wineglasses, upturned pot plants, gramophones and broken bodies. This, like the devastated station in Dead Space, is environmental storytelling at its finest, and the juxtaposition of the ugly and the beautiful becomes more pronounced the further that you investigate the game world.

While Bioshock is a parable on the dangers of objectivism, it is also a mystery in which you must hunt down Andrew Ryan (whose name is one beat away from Ayn Rand, whose writings in part inspired the game), a shadowy figure who brought Rapture into being and then allowed it to eat itself alive. This set-up brings to mind disparate works such as 1984, Angel Heart and The Island Of Doctor Moreau, as Ryan always seems to be a few steps ahead of the player, and the unveiling of his identity provides one of the game’s true pleasures.

The dark tone and nihilistic world message of Bioshock is eased slightly by the appearance of the “Little Sisters”: orphaned girls straight out of the corridors of the Overlook Hotel, who can be rescued or “harvested” for their supernatural life-force that can be used to boost your own abilities. The notion of some sort of moral choice has become de rigueur in the gaming medium, but here it is pushed right to the very forefront: the ideology of treating others badly or kindly runs throughout not only Bioshock but also its two sequels. In Bioshock 2, which again takes place in Rapture eight years after the events of the first game, you play as a “Big Daddy”, one of the lumbering humanoids who guard the Little Sisters. The way in which this relationship plays out is predictably tragic, even more so because you play a complicit role in the shaping of it. Again, Bioshock 2 knows just how to make the gamer feel uncomfortable – both compelled to find out the truth yet appalled at the thought of what that truth entails. Few games can be described as haunting – yes, Silent Hill is eerie and horrible while Shadow Of The Colossus is sad and wistful – but Bioshock 2 will remain with you after you have left Rapture for the second time.

Undoubtedly, Ken Levine and his creative team found their magnum opus in Bioshock Infinite, which swaps the underwater setting for castles in the sky: the floating, jet propelled city of Columbia. In our current political climate, the dominant themes of nativism and elitism are frighteningly apropos, as is the threat of a power-hungry lunatic – here, the terrifying Zachary Comstock – building “a new America” where minority races are used for cheap labour, naysayers are put up against the wall and, to echo F. Scott Fitzgerald, the rich get richer. Few other games have been quite so brave in their handling of controversial themes, and while the location is entirely fantastical the philosophy behind its creation is very much a spiritual gauge of our era. As with its predecessors, while playing Bioshock Infinite, you can appreciate its fluid gameplay and gorgeous graphics – it’s certainly the best-looking instalment in the series – yet you cannot help be moved by the satire that punctures the American psyche so mercilessly.

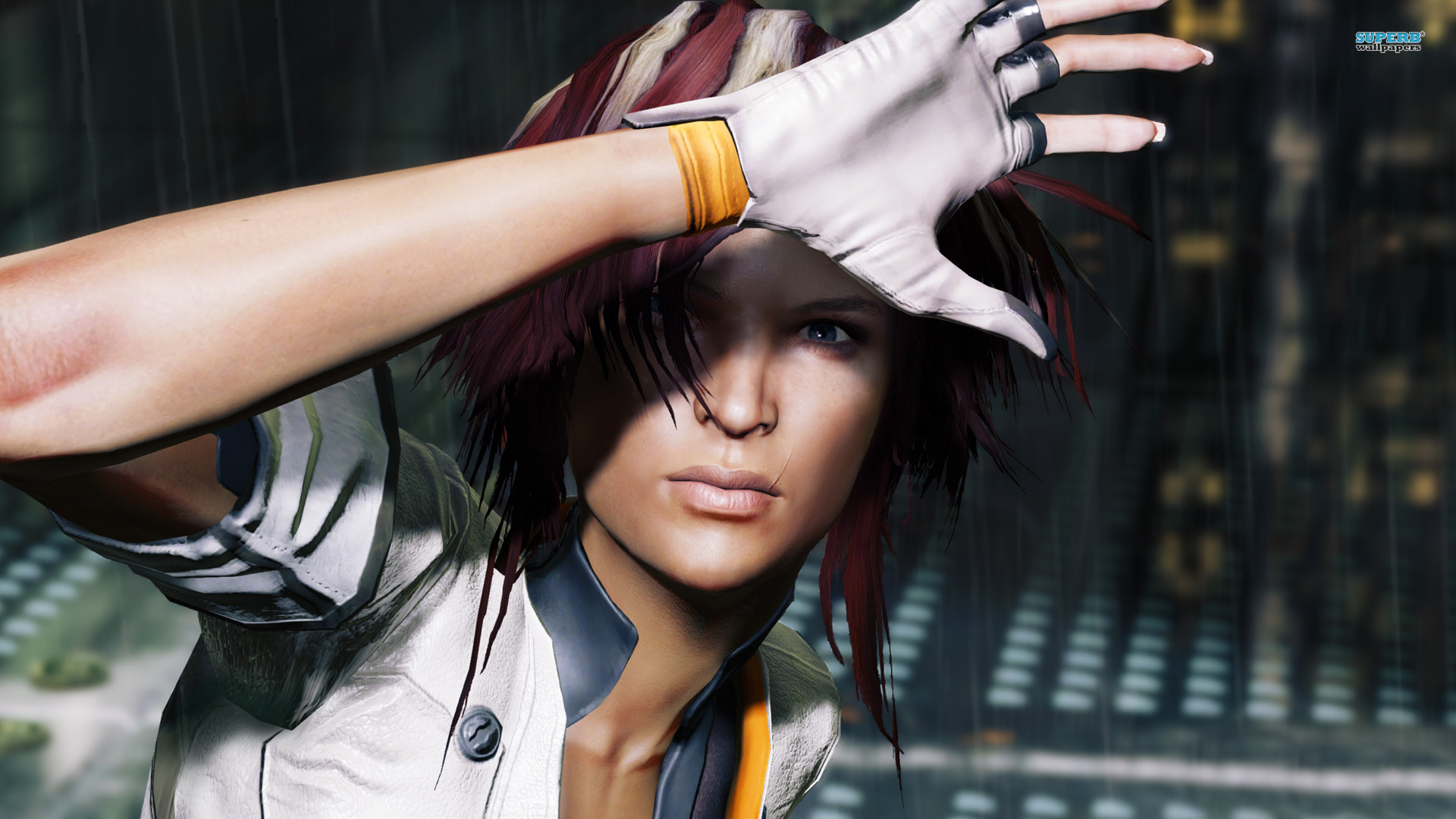

Again, this is not a game that preaches at its audience. Rather, its discourse is blended with a plot – a profoundly moving plot at that – involving quantum physics, parallel timelines and the uneasy pairing of antihero Booker DeWitt and the imprisoned Elizabeth, written with more empathy than most female characters, whose abilities allow her to tear holes in the space time continuum. This all plays out to a soundtrack of reimagined, purposefully anachronistic versions of ‘God Only Knows’, ‘Tainted Love’ and… well, to reveal more and to explain their presence would again give away too much about the knotty narrative around which Bioshock Infinite is built.

It is no overstatement to say that the Bioshock games rank among the best of our contemporary age – or perhaps any age. Yes, they have their flaws, particularly the way in which they eschew the need for the traditional end of game boss fights, yet there is so much about these games that is untraditional that the omission is unsurprising. Collected together, the three titles are further evidence that the videogame medium is as valid and powerful an art form as any other. Ross Thompson