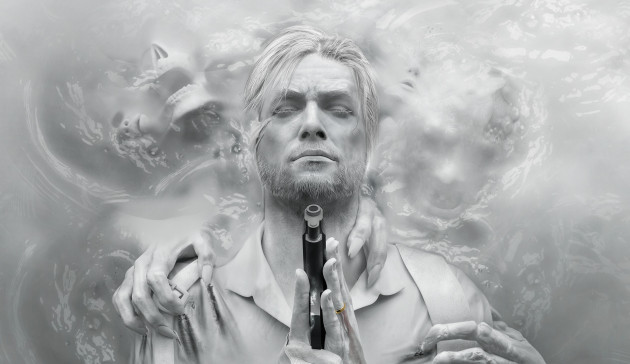

…in which we are once again plunged into the broken mind of Sebastian Castellanos. He may sound like an extra member of The Strokes but he is in fact a self-destructive police detective with, naturally, a drinking problem. You already know the drill: Sebastian is a maverick who bucks the system and is going to get his ass in a sling, but underneath his grizzled exterior he’s a sensitive soul who is searching for answers at the bottom of a bottle and trying to forget something very sad that happened to him a long time ago. One might argue that the reason for all of this existential guilt is equally clichéd: like Ethan in Heavy Rain, Sebastian is searching for a lost child, his daughter Lily. The difference is that she has been abducted by paranormal forces and taken into a supernatural other-realm that may or may not exist within the framework of his fractured psyche. The inhabitants of this twisted parallel universe are formed, like Frankenstein’s monster, from the corporal and mechanical – multi-limbed, horrifying beings that are part human, part swirling saw-blades, and who are driven a wicked temper and a primeval instinct to stomp, scalp and smush anyone who gets in their way.

Again, none of this sounds particularly original – the presence of spooky locations and characters malformed by body horror is hardly surprising given producer Shinji Mikami was one of the team responsible for launching the Resident Evil series – but what makes The Evil Within 2 so unsettling, what makes it different from other survival horror releases, is its unpredictability and its refusal to adhere to even its own internal logic. It is a work that explicitly explores the themes of mental illness and post-traumatic stress, albeit at times heavy-handedly, and this madness also shapes the game’s architecture: one moment you might be exploring a white picket fence house, the next you will be suddenly transported to a dingy industrial basement, and the next you will be lost in a version of The Black Lodge, where red carpets flow like blood and the floor is decorated with sharp geometric patterns. Doors appear where they did not exist before, the walls move, gravity stops working, cracked mirrors provide portals to yet another dimension and so on. The feeling that anything can happen at any moment and in any place is both exciting and intimidating, as it negates the long established rules to which ardent gamers will be accustomed. There are no real safe zones within The Evil Within 2, no moments to catch your breath, nothing that can be counted upon as a certainty other than the knowledge that you will die many, many times as you make your way from one end of the game to the other.

The first instalment of The Evil Within possessed many of these qualities but was stymied by niggles that made playing the game a repeatedly punishing experience. Near vertical difficulty spikes were common, particularly in the pacing of the levels themselves, where bosses and sub-bosses appeared much too regularly, particularly when you were low on the ammo and resources needed to defeat them. Coupled with the fact that the game featured a control scheme that was purposefully archaic and a stamina bar that depleted much too quickly, the player’s progress was hampered and patience was diminished in equal measures. Of course, all of these constrictions were deliberately placed to make the game even more disquieting yet they also increased frustration exponentially. None of this was helped by the fact that Sebastian, with the dress sense of an artisan barista and a gaping hole where his sense of humour should be, was prone to uttering campy dialogue that undercut the impact of the horrific things happening onscreen. Thankfully, this sequel takes great pains to remedy many of those problems. Sebastian is still one sleeve tattoo away from going full-blown hipster but at least his search for his daughter has given him believable motivation: Lily, it is revealed, is now alive and trapped somewhere inside Union, a mock all-American town that may or may not be virtual reality. As in Assassin’s Creed, it is unclear exactly at what point this simulation, if it is a simulation, begins and ends, and where it bleeds into Sebastian’s psychosis.

To reach this forsaken place, Sebastian climbs into a flotation tank not dissimilar from the ones used in the television programme Fringe, immerses himself in white liquid, and is transported to a composite of Bright Falls, Haddonfield, Eerie, Indiana and, most obviously, Silent Hill. Here, The Evil Within 2 offers up its first major change to the template. Rather than funnelling the player through a linear series of corridors and rooms, the game presents a generously sized open arena, the first of several, made for freeform exploration with lots of collectibles and branching side quests. There are still monsters to kill, chiefly “The Lost”, zombie-like former people, and other unidentifiable things that are made up of dismembered bits of other things: an early boss is a three-headed harridan that wails and cackles as she chases you around a devastated car park. The first section of the game is also built around the pursuit of a lunatic photographer fond of making “human art” – a cross between Sander Cohen from Bioshock and Jude Law’s character from The Road To Perdition – whose surrealist interludes again take the narrative in a completely different direction. The inclusion of such an oddity is another indication that developers Tango Gameworks are trying on new clothes to see how they fit, and in this instance they fit pretty well. Retro gaming fans will be pleased to know that a shooting range mini-game not too dissimilar to the one from Resident Evil 4 is also included, providing some much-needed light relief after wading through all of the other grotesquery on offer.

There is no doubt that The Evil Within 2 wears its influences on Sebastian’s tight, muscle-bound sleeve. The Shining, Don’t Look Now, Dreamscape and others are all references visually and narratively, and enjoyment can be had spotting the in-jokes and askance winks to other titles, particularly a few cheeky gags that Bethesda makes at its own expense. That all being said, this game possesses a vivid and at times gleefully unpleasant quality that is all its own.