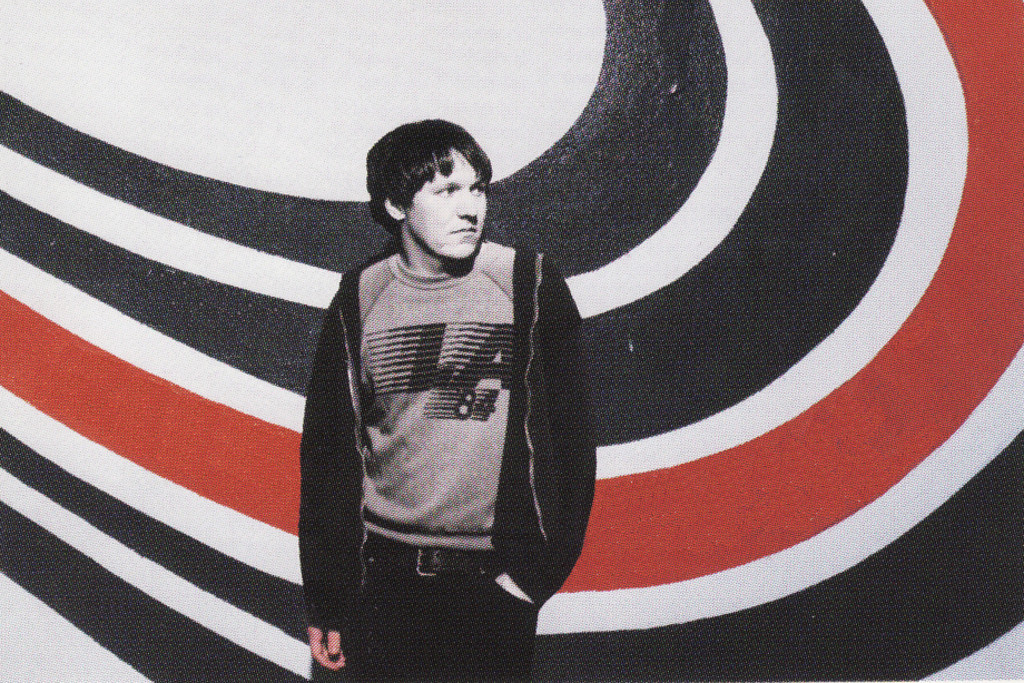

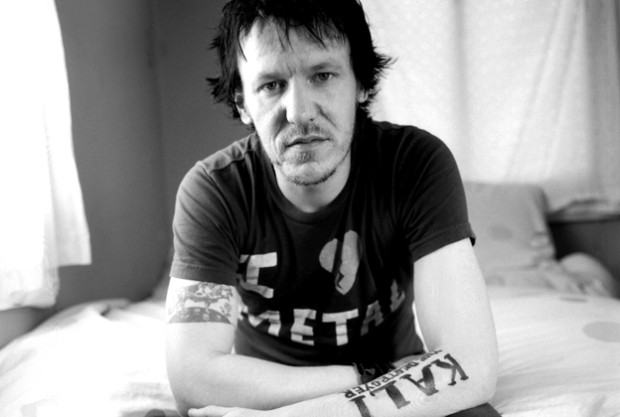

On October 21st 2003, one of the most naturally-gifted, boundlessly resonant singer-songwriters of his era, Steven Paul “Elliott” Smith bookended his story in Echo Park, California. He was thirty-four years old. Having spent several years lauded as a troubled genius, his reported suicide kickstarted the creaky old myth machine into gear once more. But whilst destined to remain “that Good Will Hunting guy” for countless people not too au courant with, say, Quasi’s discography, the outpouring of confusion and raw grief on that day in October 2003 was unprecedented, bringing into sharp focus the extent to which Smith was regarded in the lo-fi indie realm that he was instrumental in bringing about. The whims of myth, prying and hyperbole would have to wait: music had lost a bona fide one-off.

Smith struck a diminished-seventh chord somewhere deep and unplumbed, plunking each string with an uncanny persuasion that seemed to effortlessly tap into the Autumn of the soul. Mining crushing truths from the not-always blissfully content lives of himself and others, he married strange, beautiful chord changes and exquisite harmonic tangents with an almost voyeuristic lyrical grasp of the human condition – the joyous, the so-so and the grim. From his pre-solo output in Heatmiser and wonderfully homespun, searingly candid early albums including debut Roman Candle right through to the retrospectively completed From A Basement on The Hill, his recorded legacy retains a clout and majesty all its own.

Proving as divisive as various limited run documentaries of its ilk over the last few years, Nickolas Dylan Rossi’s 2014 film Heaven Adores You endeavored to trace Elliott’s literal, spiritual and psychic journey, from his Nebraskan birth and Texan childhood as Steven right through to his legendary Portlandian becoming and relocation to New York City as Elliott. Choosing to concentrate on how the bleak and blissful were rarely far removed in Elliott’s three-decade passage, the film kept a certain, often aimless distance from what one leading review called the “mucky stuff”. Whilst many criticised Rossi’s evasive detachment from the private minutiae of addiction, decline and (reported) suicide, his non-invasive exploration honoured the musician, without going to any real length to despoil the man.

While posthumous hyper-reverence is about as useful as one excavating Elvis in the hope of propelling him to a glorious third term, to those who knew him Elliott will always be much more a ricochet in the undying echo chamber of the music press, moot reviews or cosseting retrospective features such as this. To the rest of us – diehards, total newcomers, Kill Rock Stars aficionada and Good Will Hunting fanatics alike – the purest tribute we can pay, on what would have been his 50th birthday, is to don the headphones and head off into the dying day with Elliott’s brilliant sorcery in our ears. Like his heroes in Big Star and The Beatles, there’s enough earworming, inspirited twists and turns in his relatively sparse back catalogue to both last a literal lifetime and reveal a man who was, above and beyond all the apotheosis, a rare and truly outstanding musician. Brian Coney