“At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.” -TS Eliot

Nothing gave life to the potential of a common European consciousness, if you let me away with that word, quite like the neurons of railway lines that lie across its continent. It’s not just material goods and people that they carry but languages, idea and the scythe to abolish time as it once was experienced. No wonder it’s the chief motif of Kraftwerk’s masterpiece, Trans-Europe Express, forty years old this month.

You may have had Christianity before stapling the people together with a gaze fixed towards the Heavens but it was the train and the era of modernity that came puffing alongside it, that shifted man’s gaze back to Earth, to a past that had seemingly just stepped aside, lost behind a plume of smoke.

There’s no need to eviscerate the resulting carnage that such a shift in gaze unleashed, that could effectively make sadism an essential conduct for civility and a Europe disillusioned, uncloaked to the skeletons that lay in the border where its nations equated place with race. It’s only necessary to bare it in mind when thinking about the cultural environment in which the members of Kraftwerk grew up.

A Germany shamed by the recent memory of its barbarism where so much folk traditions, the traditions of the nation were implicated in the creation of a nationalist sentiment. Yet also a nation that had at its disposal a cutting edge industrial society, one with a transportation system the envy of every other nation, and an economic base difficult for most countries to rival. The fortunate product of its recent Fascist past.

Caught between a folk tradition stained through playing the Pied Piper in Germany’s recent duet with fascism, and Anglophone rock and pop infested with the trappings of consumerism, Germans were now seeing themselves through something of a shattered mirror. No longer sovereign, divided up and under the watchful gaze of two imperial’s eyes, the German nation found itself at a crossroads.

The rest of Europe was already there, slumped.

The answer, for political elites to the horror of Europe at war with itself, was integration. Out of the ashes of WWII emerged a vision of economic and political unity. The map drawn at the crossroads to find a way out of the post WWII quagmire was one of an economic union and a faith in the consumerist doctrine to shift the destination once again, to the place that lay behind the television screen and on sale in your nearest shopping centre. A cultural unity as good as any other, the destination a mere five minutes drive away.

Speaking to Jon Savage in 1991, Kraftwerk member Ralf Hutter stated,

When we started it was like, shock, silence. Where do we stand? Nothing. Classical music was of the 19th century, but in the 20th century, nothing. We had no father figures, no continuous tradition of entertainment. Through the 50s and 60s everything was Americanised, directed towards consumer behaviour. So, we were part of this ’68 movement, where suddenly there were possibilities, and we performed at happenings and art situations. Then we started just with sound, to establish some form of industrial German sound.

Silence.

Trans-Europe Express catches Europe at a kind of tabula rasa for artists, a momentary void where the past has humiliated itself and is easily brushed aside and the impulses of the present are the future. While political institutions may have been clamouring for an ideology that would replace the fervency of any -isms, Trans-Europe Express is both critique of this new European identity and an excavation of possibilities.

The industrial sounds that Kraftwerk had spent the past decade immersed in are instigated in Trans-Europe Express toward feeling the need to say something and not just be it. Taking their cue from the avant-garde pioneers of ‘sound for sounds sake’ ala Schaeffer, Kraftwerk invested in this approach the appeal of a 4/4 rhythm and an aesthetic that emphasised the machine and it’s displacement of time.

The machine has no time for the variances of the land, of the fragmentary nature of traditions that come from the various topographies, relationships, histories that attach man to place. The machine has no memory. It does not need to speak the language of locals to adapt, nor does it have any use for memory. The history that tells one nation it was conqueror and another that it was conquered no longer matters. The machine is pure presence. It subjugates all to its rhythm, blinding borders while building bridges.

The machine creates both Europe as place and Europe as identity.

Initially greeted to the organ sounds that open Trans-Europe Express, the last remnants of Europe’s previous decadence, this hedonistic impulse is quickly flattened by the oncoming repetitiveness of the rumpling repetitiveness of machine and drum, the signature ‘motorik’ rhythm, a progressive 4/4 beat that huffs and puffs with an intent that seldom hints at exhaustion.

When asked the question by interviewer Jon Savage, “Would it be right to say that one of the things you’ve been trying to do is create a kind of universal, or rather trans-national, musical language?” Ralf Hutter responded by saying, “That would be perfect. It would be too [big-]headed to say that we did it, but if it comes, it would be wonderful. We have played, and been understood, in Detroit and in Japan, and that’s the most fascinating thing that could happen. Electronic music is a kind of world music. The global village is coming, but it may be a couple of generations yet.”

To create this new global village, one needs a new language, one that opens up the possibilities of the universal.

“Europe endless. Life is timeless” repeats on the opening track.

Europe as a political ideal is endless. Life on the other hand is not political. To dream and to reckon that Kraftwerk’s relationship to their machine was a cry to the timelessness of the universe, a lament that the universe might think in binary. But our minds are moulded by words, that mean things, like the word Europe.

Europe is an endlessness based not on geographical borders but on a common culture, it is idea, pure signifier.

Behind the EU, a political institution that made the idea of Europe flesh, blood and paperwork, was that those that joined the union would result in better economic conditions for all. What gave the EU ideal political legitimacy was an expectation that the expanding industrial capabilities of Europe while fostering interdependence and specialisation, would create a materially comfortable European people, one content with their television sets and lawnmowers.

This new Europe which would emerge, would not be dogged down by old nationalist differences but instead joined in brotherhood by economic prosperity and the homogeneity of the consumerist culture that emerges within this.

Speaking to The Quietus, Kraftwerk member Karl Bartos stated of Trans-Europe Express,

“In a way it was a repetition of Autobahn. But on the other hand by using the train motif we were following the path of someone like Schaffer who made the first piece of musique concrète by only using the sounds of trains. That was in our mind also. At that time being around with Autobahn and Radioactivity we’d had enough of creating from our German heritage and rather we were considering ourselves as European musicians… And at that time the idea of the European community by using the synonym of Trans Europe Express.”

This connection of identity with the economic, of Europe. That Europe is idea. Of the ideal of economic progression but also at the heart of transportation, of the links that make Europe possible, the railway, the autobahn, these nexuses that ensure Europe is not a certain, unfixed by a geographical constraint but rather an ideal, an identity based on economic connection that is justified in consumption.

This idea of the global village has always been a very European ideal, of unity among difference.

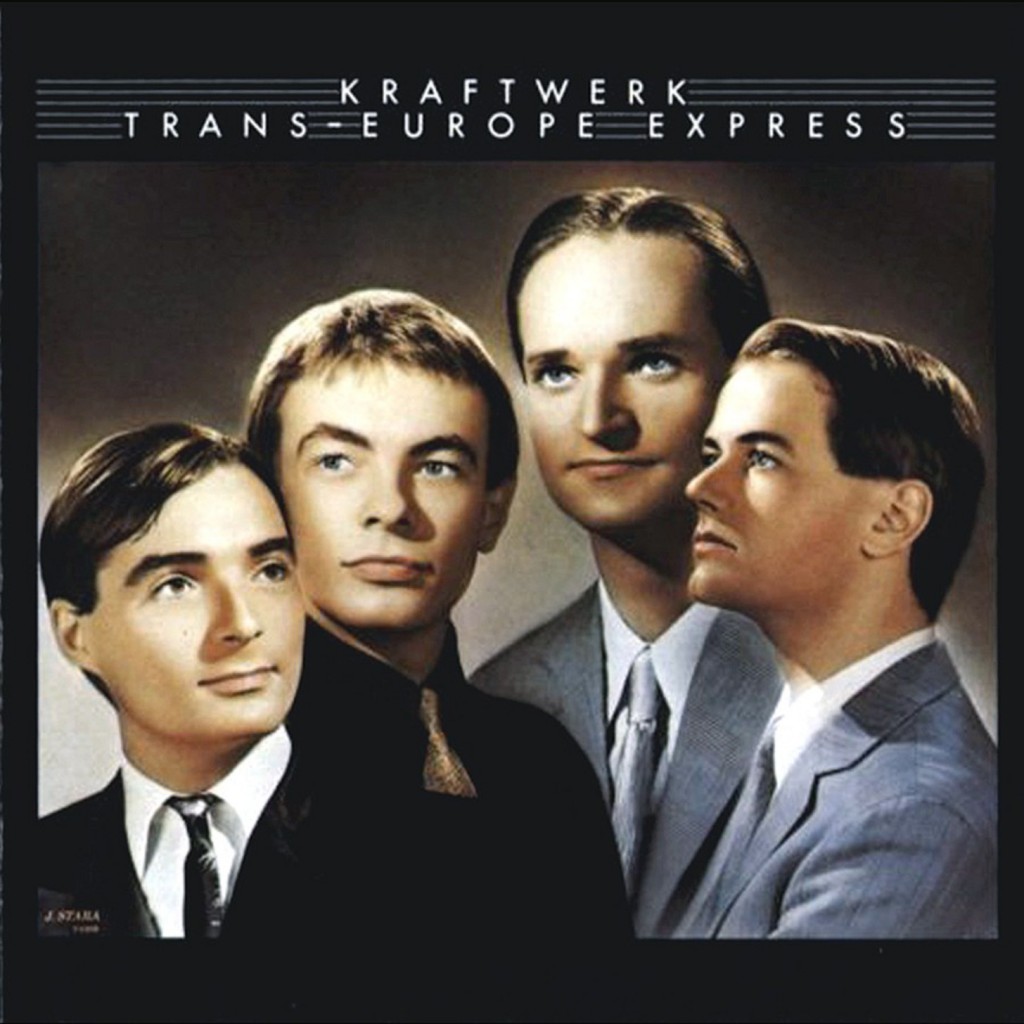

Yet apparent in Trans-Europe Express is not just a celebration or crafting of the sounds and feel that a new European ideal would feel and sound like, there is a kind of foreboding present of what this new European identity will encompass. Just look at the cover of the album. The conformity in dress is apparent, the almost inhuman like quality to each of them as if they are either robots or mannequins. Each one of them are lacking in an individuality that distinguishes one from the other.

Listen to Showroom Dummies and throughout the song of ‘We are Showroom Dummies’, and how we imagine the slow mechanical posture of the dummies as they change their pose. In the gaze of the other all become consumed. In a culture of consumerism, the compass of the self’s desire points inwards, to the self as destination.

Both Showroom Dummies and Hall of Mirrors are draped in the imagery of the endless repetition of the same. One can as easily imagine the countless apparitions of one human form in a hall of mirrors as endless dummies falling into boxes off a factory line. Yet in the former one is dealing with a kind of mass produced self, the self as product of machine while the other is self conscious, the breaking down of created identity in introspection.

‘Hall of Mirrors’ really gets into the trepidation apparent in one’s sense of self, one’s identity becoming so homogeneous that the world indeed becomes something akin to a hall of mirrors. If all identity is a creation, then ‘Hall of Mirrors’ is a realisation of this filled with the fears that one’s identity cannot hold or worse that the artist will find too much comfort in this identity and come to ignore its artifice. It is an implicit warning of the creation of a subject whether that be a ‘European’ identity or a ‘German’ one. Yet just because they are fictitious doesn’t mean that such conformity does not lend political legitimacy.

As Walter Benjamin argues in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the mechanical reproduction of an artwork ensures its repetition verbatim which induces a simultaneity in perception. In more layperson’s terms, because the work of art can be reproduced verbatim irrespective of time and place, a more homogeneous response to the stimuli occurs.

Trans-Europe Express expresses this trepidation, of mass consumerist society being the defacto identity of this new Europe and that Europe has the potential to be indeed endless. It captures the increasing conformity that is necessary for the integration of Europe to occur yet also the anxiety of the slow disintegration of any escape, of any alternative mode of being. It is only when the showroom dummies go to a club and dance, that the dummies become human.

Is this pigheaded of Kraftwerk to think that it is in a club, the environs in which the sonic experimentations of the seventies were in full zenith, was where people could be again exposed to the new and begin to question. Where we stop being dummies for a moment, dance and exist beyond consumption. Where so many radical reformulations of identity were given first expression that we now, on its maturity, have a politics primarily based on identity. The club opened up the political potential of the new, a newness that Kraftwerk viewed as at least radically human.

Forty years later and the Europe of Trans-Europe Express is no longer a familiar place. Political integration has resulted in what Vaclav Havel would call a post-totalitarian rule, where authority is no longer political but so centralized it has become authoritarian. It has led to an economic dictatorship in Greece while the confines of citizenship has led to the return in Europe of concentration camps unparalleled since the 1930’s and 40’s. Fragmentation is occurring and with Britain’s exit, national identity is becoming the bespoke currency in political parlance to answer Europe’s ineptitude in decision making.

Despite all this Trans-Europe Express feels in no way outdated. It bares the blueprint of which the shock of the new can unleash. How even when one is given only the realism of capitalism to exist within, there is a possibility to create anew. Sean Finnan

Kraftwerk play Dublin’s Bord Gais Theatre on June 2 & 3 and Belfast’s Waterfront Hall on June 4