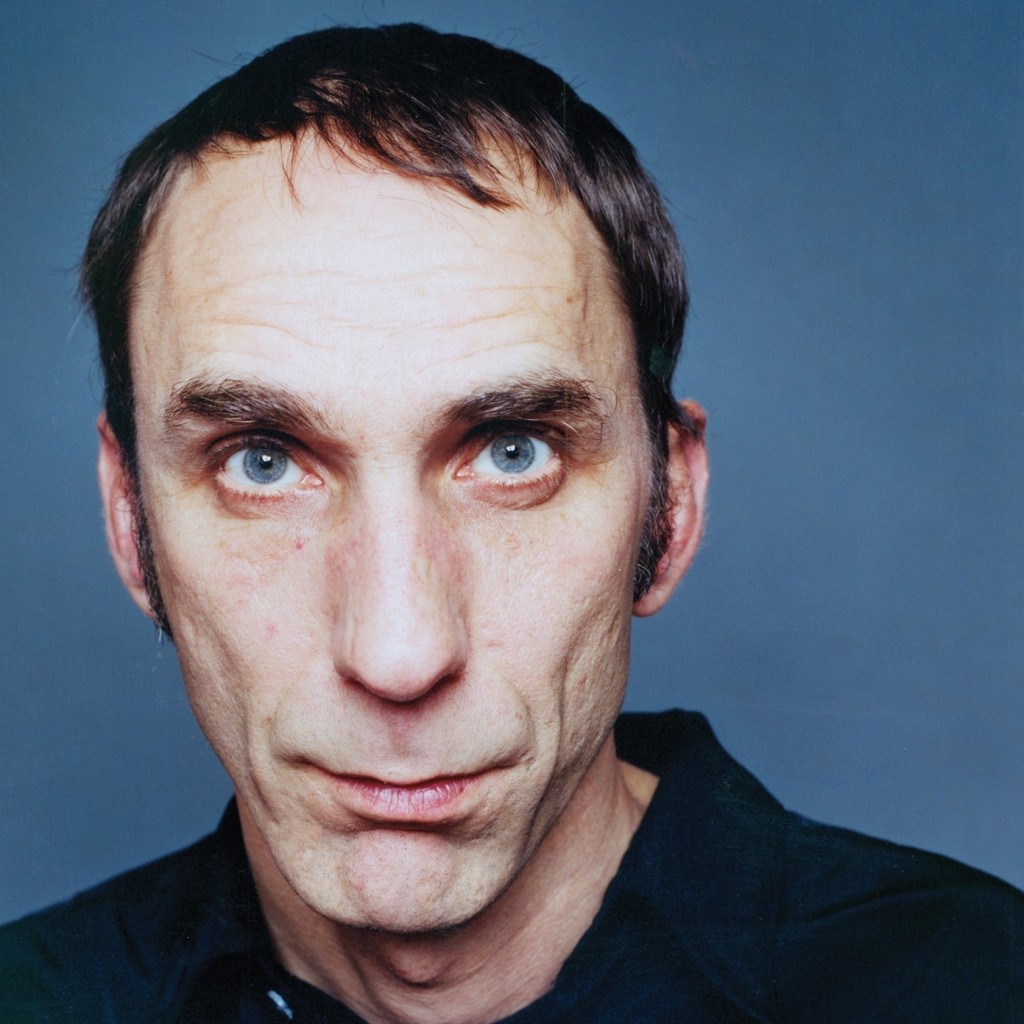

As much renown for his towering intellect and vocabulary as he is for his increasingly ambitious literary work, 51-year-old writer and journalist Will Self is, equally, widely recognised as “that clever guy from Question Time and/or Shooting Stars“. Ahead of his talk at this year’s Cathedral Quarter Arts Festival, Brian Coney happily risks becoming fully aware of his own intellectual impotency in discussing Self’s beloved London, the oft-misunderstood approach ‘psychogeography’ and the author’s latest, arguably most accomplished novel, the Man Booker Prize-nominated Umbrella.

You have, of course, recently published Umbrella. At the risk if being too general, what type of work did you set out to create? Was “astonishing” your readers still on the agenda?

Well, inasmuch as I have an idea of readers at all, they are tautologous figure. The ideal ones are simply those people who wish to read exactly what I’ve written. I made that remark about ‘astonishing’ years ago, simply to distance myself from writers who aim to entertain, or those who wish to produce cathartic effects in their readers through providing them with characters that they can – in the contemporary idiom – identify with. I never really believed in my own statement. I said it to my publisher at the time and in the way that publishers do she thought it a good hook line and slapped it on the cover of the proof we were sending out (it was ‘How the Dead Live’ I think…) So, in sum: I don’t really write to do anything much but pay the rent, interact with the world as I find it, and create works that have some sort of internal integrity – of form, of style, of manner.

What’s the relationship between psychiatric and technological disorder in Umbrella? How resonant are the themes in modern UK society?

Well, it’s neurological disorder in Umbrella; Encephalitis lethargica, a nerological disease related to Parkinsonism. It’s still very mysterious. True… the post-encephalitic patients that ended up in long-term psychiatric institutions came to resemble the insane through an awful sort of assimilation or morphic resonance. What I was interested in was the idea that this pathology – which is characterised by ceaseless and repetitive tics – verbal, muscular, psychic – could somehow make of an individual a personification of the impact of technology on 20th century western civilization. Thus the condition becomes both a catchall and a forcing ground for all sort of ideas/positions on the interrelation between the human psyche and the technological revolution. But, no… I don’t think the kind of mechanisation discussed in Umbrella is in any direct way responsible for psychosis, say, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. We owe the burgeoning of these malaises to later technological developments such as the atomic bomb and these I will cover in the next installment of the trilogy, Shark.

One reviewer said, “Whether Umbrella takes experimental fiction beyond the magnificent cul-de-sac into which Joyce steered it is doubtful.” Firstly, was it your intention to push certain “token” literary confines and how important is to you to be recognised as an experimental writer?

It’s not very important for me to be recognised as anything much. I decided to adopt the continuous present, stream of consciousness and monopolised narration for Umbrella because I think they bring readers closer to the emotional truth of lived lives – its chaos, its sensuality, its evanescence – that’s all. This was never intended to be a ‘book about books’ – such a pursuit, for a novelist, is an abomination.

Umbrella is the first part of a trilogy. To what extent do you view your literary work as a continuous canon? Do you view your output as a body of work of sorts?

Absolutely. This is why characters such as Zack Busner recur throughout the different narratives. An early reviewer of my first book described it as ‘a series of feature articles about a parallel world’ – and I liked that, it rang true to me; it rang true to my feeling that truth itself is only a matter of coherence between phenomena, rather than a function of their correspondence to a world which, ultimately, we can have little certain knowledge of. All fictions are, of necessity, feature articles about parallel worlds – one of which we happen to live in.

From what I have seen in certain articles, your workspace is quite a feat in controlled chaos. On a day-to-day basis, how do you balance your literary and non-literary pursuits, amongst the mere act of just being Will Self?

I write fiction in the mornings – the earlier the better, when the threads of the dreamscape still warp with the weft of waking consciousness, then I find it easier to suspend disbelief. I do other stuff in the afternoons. My older children have left home – the youngest can take himself to school – so family stuff is confined to the late afternoon and evenings. That’s it.

You are widely regarded as one of our era’s true intellectuals. Have you found your voraciousness for reading and autodidactism diminished by time and/or personal circumstances?

Not really. If anything I read more now than ever before and after a long furlough from very serious, academic reading, having taken an academic job I find myself reading the heavy stuff again and hopefully expanding my range. Teaching seminars that relate great fiction to ideas is… stimulating – as Larry David’s fat agent Geoff (in Curb Your Enthusiasm) would say: ‘Who knew!?’

Regarding the very real, increasingly apparent decline of the novel, I assume you have an ambivalent outlook on the whole thing? Does it really matter if we’re all using kindles in 15 years?

Well, the Kindle is nothing to do with the decline of the novel. That’s a function of the different forms of culture and entertainment that compete for potential readers’ consciousnesses, not the platforms on which they read/view. Personally I enthusiastically embrace electronic reading and have no real patience for those who fetishise the book as an artefact. No, the decline of the novel – and the status of the writer – is because we are in an interregnum between dominant narrative forms. The novel survived as a sort of Greece to the Rome of the movies, now the movies’ hegemony is ended the novel has suffered collateral damage but I don’t think it will ever die out. It’s an art form that allows for such an exercise of imagination on the part of its consumers and once they’ve experienced this they can never really find satisfaction elsewhere.

I was reading The Man of the Crowd by Poe the other day and suddenly became aware that the protagonist possessed that acute abandon of direction that makes taking in a small part of the world in a wilfully conscious manner a massively enjoyable experience. Could you please attempt to sum up psychogeography as something we can all avail of?

The protagonist of The Man of the Crowd is quite as driven as the eponymous antihero of the sorry, who is compelled to be with others and so circumabulates the city day and night. The narrator is indeed a classic – if neurotic – flaneur, and his disjunction from the lived lives of the people around him is just as entire. My brand of psychogeography – like that of the French Situationists – is part of a distinct attack on the way late capitalism forces people onto constrained relationships with place and travel, relationships defined by the equation of time and money; I walk, because this frees me from the man/machine matrix, and I take if not randomised paths across the urban scape (for what could such things be?), then ones which are wilfully perverse. Psychogeography frees us by making us explorers in our own backyards – capitalism wishes place to be fungible (tradeable on the world market), that’s what tourism is all about, but in submitting to this runbric we lose our sense of place as something sensual and emotional – walking in particular (by forcing us to measure distance with our own physical form and capability) returns place to us, and that’s highly liberating.

You will soon be giving a talk at CQAF. What impels you to give these talks and what is on the cards for this one?

I get paid. I don’t have a private income or a sinecure – this is how I make my living. It helps to publicise my books and encourage people to read them. The number of serious writers in the archipelago of Britain and Ireland who can make a living from their printed words alone could be comfortably fitted in the average suburban drawing room – I’m not one of them. As for this event, I’ll read from my latest book… take questions…

You have achieved and created some remarkable, inspiring things in your life. Out of all of your endeavours, what gives you the most pleasure and what have you got in the works for the next few months?

Well, my work is a praxis. It’s the way I relate to and inhabit the world. Once a book – or any piece of work – has been completed, it’s left the building. What gives me the greatest pleasure (and equally, pain) is the book I’m working on now.

Finally, how do you quantify success and, more importantly, happiness? Are you, taking a step outside of your person, a successful and happy person?

Well, plenty of writers, once their books are on the syllabus or have been translated into so many languages or sold so many copies, get what I call the ‘delusion of posterity’; and become very pompous as a result of this I hope it’s a delusion I’ll never succumb to. We are all the bird flitting through Beowulf’s hall – life is short… evanescent. I like Oscar’s apothegm: ‘Life is a dream that keeps me from sleeping’. Success, happiness – these are terms I don’t altogether understand.

Will Self appears at Cathedral Quarters Arts Festival at on Friday, May 3pm – Black Box, 6pm.