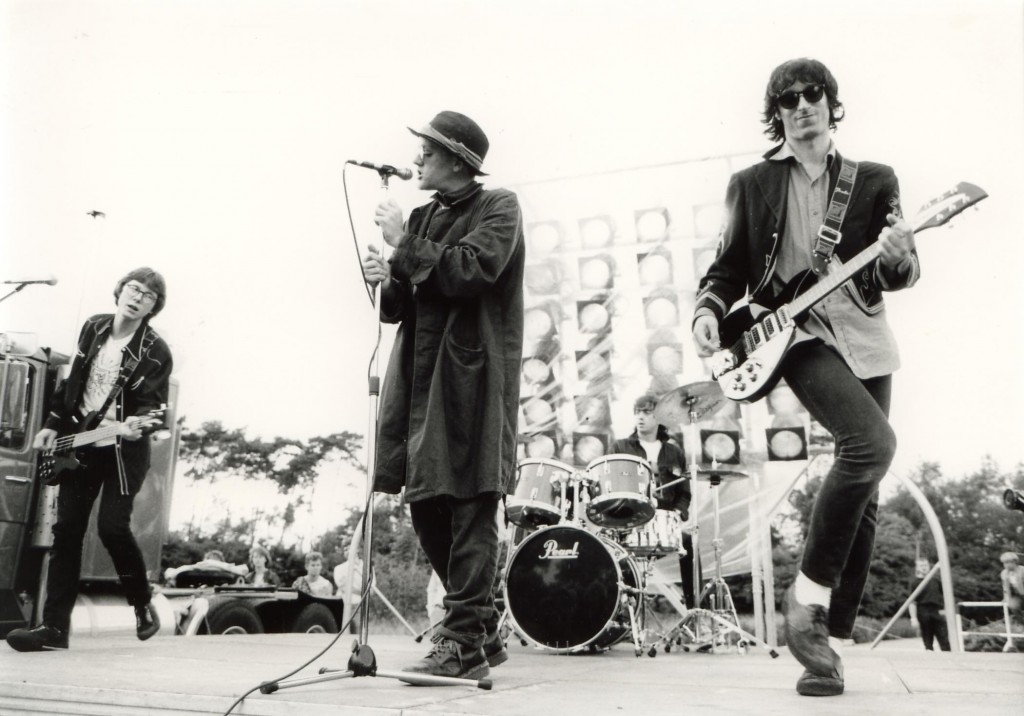

Some records become bigger than the music contained on them. The infamous Exile on Main St. sessions are more mythologised and discussed than the music they produced. Chinese Democracy will always be better remembered for its protracted development than for its songs. REM’s debut release, Chronic Town, brings its own baggage to the table: the birth of college-rock as we know it. The record that breathed new life into the electric guitar as a creative instrument in an era awash with New Wave synths. A reputation for being enigmatic and inscrutable, with secrets hidden in every groove. The stories surrounding the making of the EP have themselves become part of the record’s legend: the initial gig in a rundown church for a friend’s birthday party. Michael Stipe’s vocal parts and Mike Mills’ bass lines recorded outside, away from the other instrumentation. The speed with which the recordings were made – nine songs in three days, with only five being retained in the final track listing.

With so much weight and mystery connected to it, Chronic Town can from a distance seem uninviting; a record for scholars and connoisseurs to study and quietly mull over rather than something that would fit on a party playlist. The opening notes of the terrific first track ‘Wolves, Lower’, however, should be more than enough to cast off those misconceptions and reveal the EP for what it was always intended to be: a breathless, exhilarating piece of work, topped with obtuse mumbling that nevertheless had fantastic singalong potential. It marks the opening act of a group out to show the world that it was “not only deadlier, but smarter too”, as Stipe growls on ‘1,000,000’ with remarkable prescience.

‘Wolves, Lower’ is a fitting introduction in this regard. The combination of Peter Buck’s quick arpeggios, Bill Berry’s staccato percussion and Stipe’s low, semi-enunciated murmurs make the verses a nervy, pulse-quickening affair, making the soaring release of the chorus all the more potent. The sound of Stipe melodically bursting into tears during the chorus (or not – the question of symbolism or the lack thereof in Chronic Town is one the band insisted on leaving open to interpretation, giving weight to the record’s ‘enigmatic’ reputation), not to mention the first appearance proper of Mills’ wistful vocal harmonies, bolster the already claustrophobic atmosphere and only add to the song’s essential status. As an opening it’s practically perfect, and it only gets better from there.

Written before even ‘Radio Free Europe’ was initially drafted up, ‘Gardening at Night’ was REM’s first proper classic and is still a perennial favourite of the band, as evidenced by the fact that the song has been released no less than nine times in various forms across numerous compilations. Bill Berry once noted that the song was inspired by a friend’s request to go ‘night gardening’ at the side of the road after an evening spent drinking. That being said, ‘Gardening at Night’ has been the subject of endless interpretations over the years, the most popular being that the song is about Stipe’s father, drug use, sex or even just gardening at night itself. Stipe’s vocal does little to enlighten such conclusions; besides the chorus and a couple of stray words like “money” and “pocket change”, there are barely any clues to the song’s subject matter. As one of the earliest examples of REM’s ability to paint a picture through evocative images rather than narrative, “Gardening at Night” was certainly a successful experiment to have garnered such a wide array of responses. However, the song is most notable for simply being one hell of a pop song. The hooks are glistening, the melodies are infectious, the chorus is one of the great early REM singalongs and it’s even great to dance to, an asset that made the song the breakout hit from Chronic Town in the local Georgia area before Murmur broke them further afield.

For all its good points however, ‘Gardening at Night’ still isn’t the best track on the EP. Despite such esteemed company, the high point of Chronic Town is the magnificent ‘Carnival of Sorts (Box Cars)’, a song that ticks every box REM set out to achieve in 1982 and one of my personal favourite songs the group ever released. Beginning with the sounds of a carnival that has faded with time, the track soon changes tack and jumps into a verse strewn with night time imagery and the implication that unsavoury deeds are being planned by shadowy figures under the lights of the rollercoaster (“Gentlemen, don’t get caught”). This is accompanied by some of the most genuinely exhilarating instrumentation REM ever produced, an achievement that gives the track a sense of urgency that was sadly absent for much of Murmur. The Mills harmonies are as catchy as ever, and the group even managed to nail a proto version of soft/loud dynamics 7 years before Surfer Rosa arrived. ‘Carnival of Sorts’ marks the end point of Side A of Chronic Town, which is still my favourite REM record side.

Unfortunately, with such a string of great songs on one side, the flip side was always going to suffer in comparison. While both ‘1,000,000’ and ‘Stumble’ are fine songs in their own right, in comparison to the works on Side A they are much less satisfying than they should have been. ‘Stumble’ in particular starts out quite strong (with good reason – it was a live favourite at the time) but drags out for far too long with intermittent sonic experiments in the final minutes that hint at attempts to fill space rather than anything else. ‘1,000,000’ meanwhile is propulsive, but never manages to hit the peaks it could have reached for.

So, to conclude: one of the finest REM records ever produced, one that they struggled to better with subsequent releases (although Murmur came close) and one to consider for both rigorous study and last call at the jukebox. It’s the gift that just keeps on giving. Mark Jones