When all is said and done, Lou Reed was never the easiest figure to love. For someone who is so intrinsic to the very notion of what we consider popular music to be, for someone who tore up the rulebook so fundamentally and set us all free, it’s rarely been an easy ride.

And now that he has moved on, that journey will only become more difficult.

Like all the truly great artists, to be “into” Lou Reed is to be “into” a variety of different personas, of different masks, of different ideologies. The snarling twenty-something, sunglasses strapped permanently to his face, spitting in the face of love. The pseudo-hippy, trying to be laid back, but failing. The pop star. The glam queen. The avant-grade experimentalist, pushing further and further into the unknown. The addict. The drunk. The romantic.

He was all of these things, and sometimes, he was none of them. For myself, The Velvet Underground came first, a school friend bringing White Light/White Heat into the common room, just to see what would happen. It didn’t last long on the stereo, but the impact was nothing short of seismic. For those few of us who were able to listen, it was like the world went from black and white to technicolour, a “lifting of the veil” that somehow changed everything.

The old, oft-trotted out statement is that very few people ever heard the Velvets, but those that did went out and formed bands, or became artists, or started writing. And looking back at the impact they had in a Northern Irish schoolroom in the mid-90s, I can see the truth in it. They were more than a band, they were a liberation.

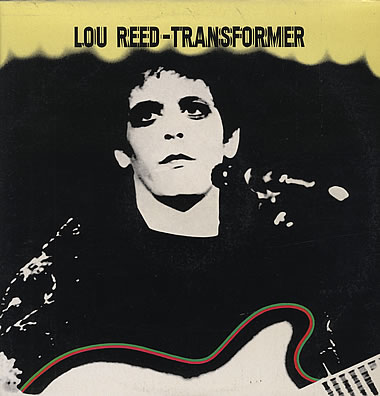

An interest in everything Lou Reed had ever put his name to quickly followed, devouring records like Transformer (glammy camp with an underlying seam of pure emotion that is inescapable), Berlin (the awkward and provocative follow up, beloved by The True Fan), or Coney Island Baby (subtle and romantic, an underrated classic). Along the way, black clothes were worn, sunglasses were donned, and a copy of his punishing, avant-garde endurance-fest, Metal Machine Music, was purchased. And, to a surprisingly large extent, enjoyed.

But as the years went by, that love began to strain and chafe. Lou’s late seventies period isn’t without its great rewards, but it ain’t for the faint hearted, either, and sometimes the buried treasure is too well hidden. For someone who was hailed as the ‘Godfather of Punk’, his output during those crucial years was patchy, the ‘idea’ of Lou Reed sustaining him better than his actual songs were.

The eighties weren’t much better, Lou struggling to find a place in this increasingly sanitised world, ill at ease with the sheen of pop music, but equally incapable of reaching out to an underground that would have embraced him with open arms. However, returning to his spiritual muse in 1989 with New York, Lou was able to tap right back into that sensibility that made him so vital in the first place. Taking the Street, with all its sights and sounds, and all those characters that lurk in the darkness, Lou was once again able to open our minds to the beauty and danger of a world that lay outside our windows.

The next ten years would find him making a stream of confident albums that, if not quite remarkable in their content, showed this elder statesman growing more confident in his own shoes. A pointless reunion with the Velvet Underground reminded us that he wasn’t quite ready for sainthood just yet, with his behaviour towards his former bandmates still leaving a bitter taste in the mouth.

And then, just when it was all becoming a little too comfortable, Lou Reed re-embraced his inner curmudgeon, challenging preconceptions on a whim, almost daring us to call “BULLSHIT” on him. For all the reverence that he can evidently still command, the last ten years have seen Lou Reed testing the patience of even the most ardent fan. His musical version of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven delighted few, whilst his 2011 collaboration with Metallica, Lulu, must surely rank up there as one of the least anticipated albums of all time, a union that existed only in the twisted dreams of sadists. And it was on this record that one of the most iconic songwriters of the twentieth century bowed out, the album becoming his final release.

The death of Lou Reed carries such a shock with it because, if Lulu is anything to judge by, he wasn’t done with us yet. Like it or loath it, Lou Reed remained one of the most challenging and provocative talents that rock and roll has ever seen, managing to be subversive and creatively restless, even during a time when most people would be settling down into the twilight of their lives.

All over the world, there are people doing their own thing, fighting themselves and every preconception of the world they can encounter, and they’re doing it – whether they know it or not – because of Lou Reed. In a creative idiom struggling to grasp for legitimacy, Lou Reed was a blast of antagonistically thrilling rebellion, as well as simultaneously embodying that great intelligence that rock and roll so dearly strove to possess.

He was one of the masters, and as the world of rock and roll struggles to repurpose itself for the needs of the current age, we’re going to miss him more with each passing year. Steven Rainey