The tenth and final episode of Louis CK’s experimental online-self-distributed series, Horace and Pete, arrived in subscribers’ inboxes on Saturday to no fanfare or announcement of the series’ conclusion – simply an email from CK saying he had nothing clever to say about it. It was written, filmed and directed by Louie in the week prior to each release, evidenced by the highly topical barroom discussion, with even Hulk Hogan’s Gawker sex tape discussed.

In its finest moments, Horace & Pete feels like zeitgeist-capturing cult television event, and for anyone into it, the personal email from Louis was the highlight of the week in entertainment, in a move that threatens to posit CK as the Radiohead of standup comedy, delivering its content in as unique as way as the stuff inside. In a move so incredibly in line with himself, CK simply released the show, let people know it existed, and left people to fill in the blanks and make their mind up free of extraneous press coverage and, ultimately, preconceived notions – give or take a tirade about Donald Trump.

I won’t give any plot spoilers, as this is essentially an extended recommendation & discussion for a show we think you might enjoy – and this is very much a character show. Quite honestly, you’ll know if you like it by the first intermission. You’ll probably know after the first section of dialogue. You’ll have your views challenged, and you might wonder if you can ever really choose your own path. You’ll find yourself endlessly frustrated at every character at least once per exchange, and their inability to deal with their circumstances. And you might have a little too much light cast upon your own flaws and hangups along the way.

In many ways, Horace and Pete is the boundary-pushing, panoramic vision of his other pet project Louie – with this brimming with even more ambitious ideas – filtered through the palatable lens of Lucky Louie – his early one-season traditional multi-camera live-audience sitcom about a miserable couple; broader in scope, more concisely pointed its direction. and they’re kitchen sink stuff.

It’s set in a bar that’s been open for a century, with the hook being the long line of siblings named Horace & Pete, who’ve each run the bar for generations, and the catch being that the bar-cum-institution is a trap within which the abusive patriarchal figures of the lineage have centred themselves and everyone around them. The institution, built on shaky foundations to begin with, has been irreparably damaged by the system that it’s fed and feeds into, and this conceit allows CK to go full-on kitchen sink, using almost every available scapegoat – generational, gender, racial divides, privilege, and the connection between each – to best portray the stilted, cyclical, consistently inconsistent patchwork society in which we exist; all the while asking where difference lies between existing and living.

Everyone and no-one is in the line of fire, really. Every issue is given its voice and a fair trial. Discussions where each participant attempts to steer every exchange to meet their own agenda, with minimal middle-ground or compromise. It’s a fairly strong, if blunt, observation about the kneejerk-culture in which debate often takes place nowadays. The bar really functions as an echo chamber of projection of self-loathing, where everyone attempts to find a scapegoat for their neuroses, and no topic is off-limits.

Horace & Pete fills the void between television, theatre and that old chestnut: deep-rooted human issues, both inside and out. It’s a cruel, cruel show, heartless in ways many will never experience first hand, but at its core is the genuine beat of that classic argument: nature vs nurture. Can you overcome your wiring and make something of yourself in spite of yourself and who you’re surrounded by? We grow to know them, and feel some sympathy, even empathy towards at least some aspects of a collection of people who fight (in vain) this battle daily.

I’ve never much appreciated stage plays, so I suppose that makes me something of a philistine for jumping onboard and saying that Louis CK‘s Horace and Pete is one of, if not the greatest single season of a show I’ve ever seen. But we see what we want to see: some ordinary schlub with aspirations of greatness is what he’s always been about, to some degree; the fact that something with this level of ambition and audacity can come from some guy’s independent pet project, week on week.

At this stage in his career, Louis has pushed the boundaries of freedom of expression within comedy – with its limit surely being his audacious recent SNL opening – and, separately, his level of artistic experimentation (see: Louie – Untitled) to the point where he has the power to do little wrong in the eyes of networks and the paying audience. And thankfully, he’s using this power for good, with each episode lasting anywhere between 30 and 67 minutes, which is exactly as much as is ever needed to create the tension and sense of foreboding CK loves. The effect is such that at any given time in an episode, it feels as though anything can – and anything does – happen. Murphy’s Law: The Series.

Obviously, a theatrical show is relies heavily on its cast, and the degree of pathos in these performances is the lynchpin. CK displays his acting chops to the fullest extent audiences have yet seen, most notably in an episode that consists of one long conversation between himself (Horace) and his ex-wife. Steve Buscemi plays the titular, schizophrenic Pete, who life just keeps shitting on. He’s easily the most warm-hearted, sympathetic figure in the series, and his arc is one of the few obviously dramatic aspects to an otherwise low-key show. You also have the scene-commanding Alan Alda as the sexist, racist, homophobic, hilariously hypocritical – a trait well-seen in each character – Uncle Pete, and, perhaps most worthy of note: Edie Falco, as Horace’s cancer-suffering (increasingly understandably) antagonistic sister as probably the acting performance of this show, if not her entire career – including The Sopranos.

Among the regulars in the bar are bitter American conservative played by genuine New York conservative comic, Nick DiPaolo, a (genuinely) profoundly deadpan showing from one-liner king Stephen Wright as a somewhat philosophical barfly, younger talents like Aidy Bryant as Horace’s daughter-who-hates-him and is going through a process of learning not to hate. There’s even a wonderful cameo from the major of New York & Paul Simon, who composed the aptly delicate theme for Horace and Pete.

The direction of the show builds towards something prodded at by modern masterpieces like The Wire, The Sopranos & Mad Men, and the worldview Louie has increasingly elaborated on in his stand-up and on Louie, for which he had already set a precedent for integrity in taking a relatively low-budget deal on FX in order to gain complete freedom for instead of compromising on a big-money HBO deal.

In many ways, this show has been inevitable. Louie has been eyeballing complete artistic freedom since his experimental self-released films in the ‘90s, carefully anchoring his lofty ambition with the fact he’s just a sad, middle-aged man with the same hangups he’s always harboured. He’s been a sad middle-aged man, really, since he first took up stand-up. What Louie is, is a master of context. There are topics no comedian is ‘allowed’ to cover here, but CK gets away with it by his knack for articulating his self-loathing into a point about people at large.

The best comedy is derived from tragedy, and not one show knows this better than Horace & Pete. Some of the most genuine belly laughs I’ve ever gotten from a piece of entertainment come in its moments of levity. It’s Cheers, except people don’t give a shit what your name is, or what you want to drink, and when you ask for a cold one, it probably isn’t cold, and we don’t do cocktails here. It’s a comedy in the broadest sense, and we’re the punchline, and it might be the best single series to grace screens for quite some time. It certainly is for me.

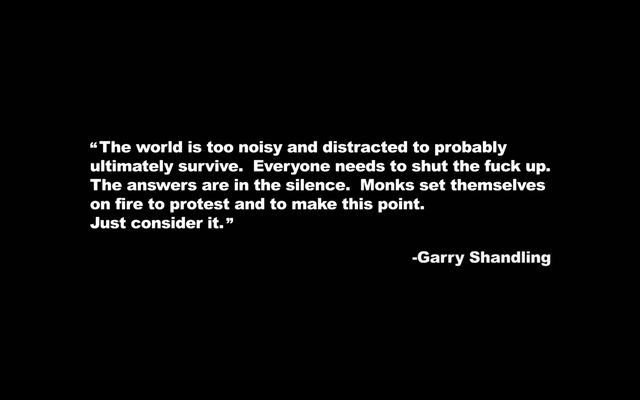

Perhaps the most succinct part of CK’s message here, is the use of a quote from the late Garry Shandling, at the end of the penultimate episode. Stevie Lennox

Buy the show. It costs around $3 per episode directly from CK, with no middle-man.