In 1972, King Crimson were in a bit of a mess.

The band had been one of the leading lights of Britain’s art-rock scene, taking the ideas and recording approach of The Beatles to an extreme undreamed of. Their 1969 debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King, rewrote the book on what rock and roll could do, but line-up changes had destabilised the band over a series of albums to such an extent where the sole remaining member was guitar virtuoso Robert Fripp, everyone else having quit in the midst of a tour, deciding they’d rather play the blues.

Playing on-stage, sat on a stool, with his frizz of hair and spectacles, Fripp cut a curious figure in rock, an almost academic sensibility inspiring his neo-classical compositions. While Crimson had their fair share of ballads about the ladies on the road (somewhat regrettably, with the benefit of hindsight), they’d made their name with a series of heavy duty epics, apocalyptic soundscapes which used layer and texture as a weapon, sounding like the clarion call of the end of the world.

But if Fripp didn’t get a new band together, the only noise he’d be making in the future would be silence.

Enter Bill Bruford, drummer extraordinaire. Cutting his teeth in progressive rockers Yes, Bruford’s intricate drumming style had put him at the front of the pack, and elevated Yes to one of the UK’s most visible rock bands. 1972’s Close to the Edge was pretty much as good as it gets, and the band were set to take over the world. So, of course, he’d decided to pack it in.

With canny timing, Fripp gave Bruford a call, letting the drummer of one of the UK’s most successful bands know that he was now ready to graduate to playing with King Crimson. The pairing of Fripp and Bruford gave this new incarnation of Crimson a muscular backbone, and an exploratory sensibility that they’d previously lacked. Composition and arrangement were the hallmarks of previous Crimson incarnations. This time around, things were going to be different.

The line-up was fleshed out with violinist David Cross, whose improvisational skills could take the band into uncharted territory. Bolstering the rhythm section, Jamie Muir had come from a jazz background. With an array of pots, pans, tubes, and other sundry objects, it was clear that a simple 4/4 beat was unlikely to be on the agenda.

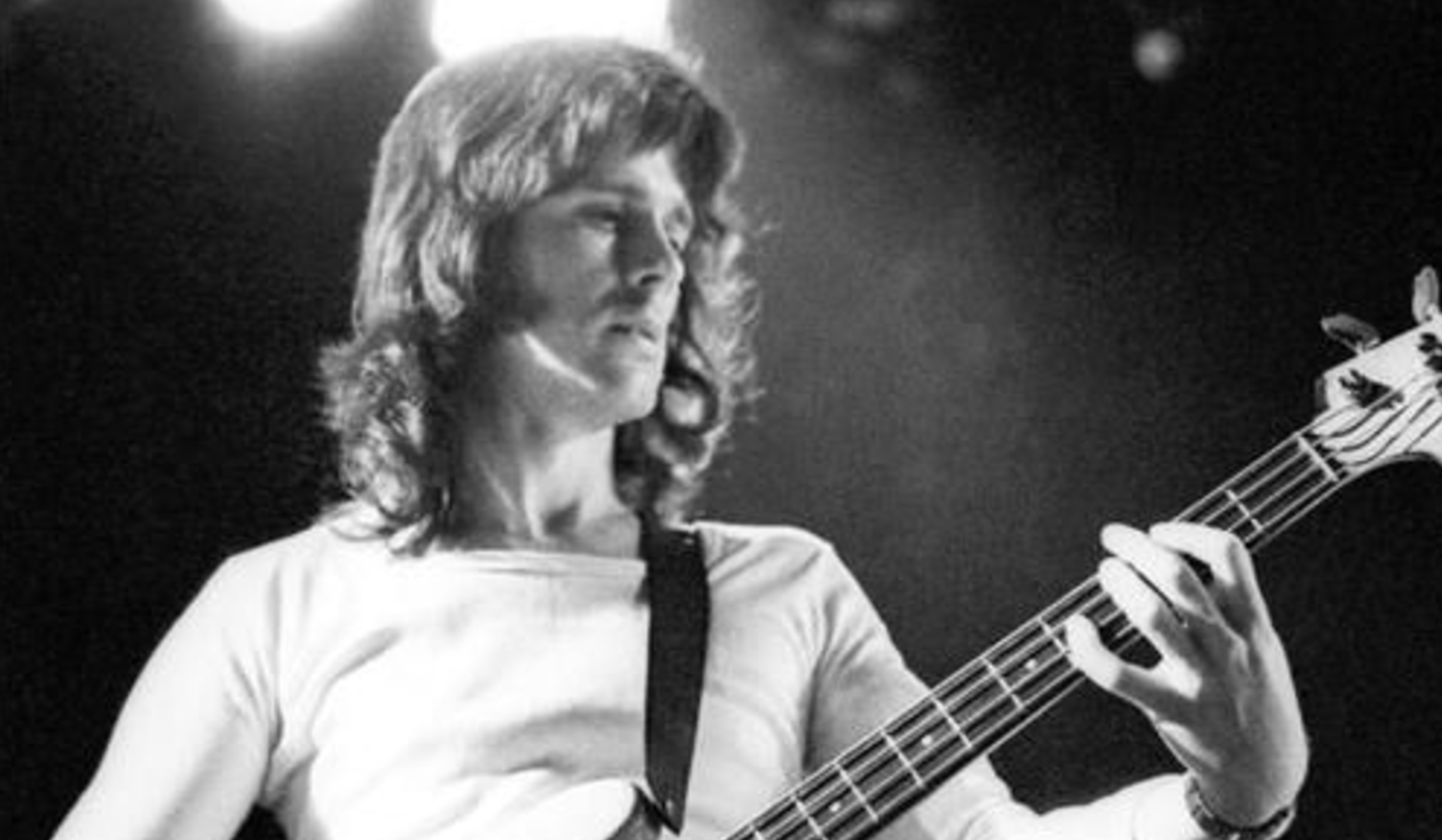

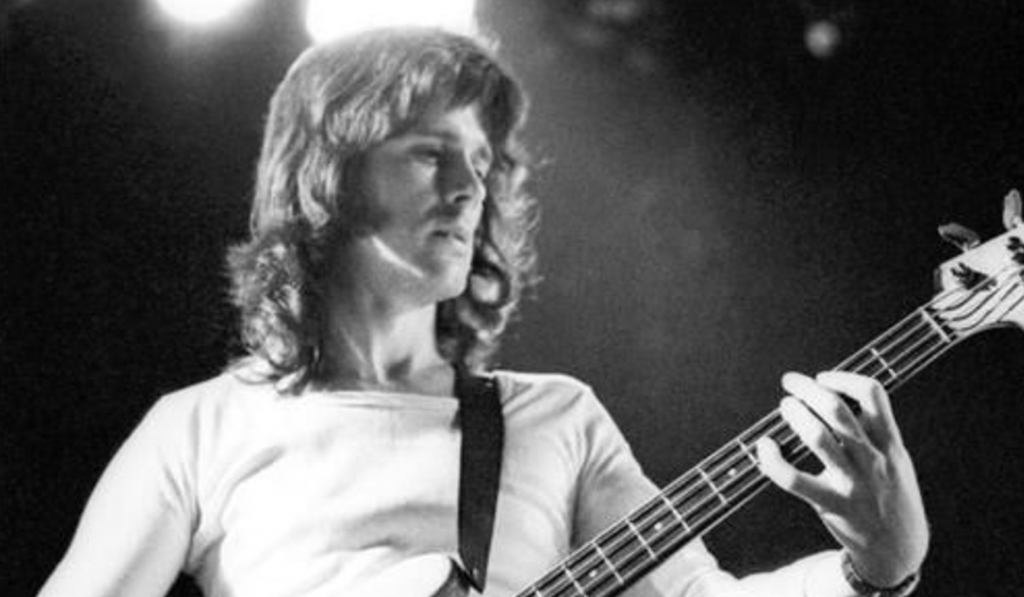

All previous iterations of King Crimson had featured a singing bassist, and amidst all the drastic changes, this new line-up was to be no different. John Wetton had previously made a name for himself on the live circuit in a number of bands, none of which had really broken through to larger success. A stint in psychedelic folk rockers Family had brought him to wider attention, but the invitation from Fripp couldn’t have come at a better time. Standing in the shadows, he’d perfected a fluid style of playing, at times jagged and spiky, or tenderly weaving its way around the music. Possessing a fine voice, this sideman was ready to step up to the front of the stage. All that was needed was the songs.

1973’s Larks Tongues in Aspic was a courageous new sound in rock music. Drawing from jazz fusion, progressive rock, classical, and folk, the six songs contained within revitalised King Crimson, and today stand as a high-water mark for what progressive rock could achieve. The title track, spread into two pieces which bookend the album, opens as a glistening soundscape, tinkling bells and pastoral sounds drifting by the listener, as if we are moving through a series of gossamer veils.

But amidst the beauty and the sense of serenity, an unease grows, a gnawing tension that something is not quite right. The pressure grows, each player pushing themselves forwards until they meld together as one, announcing King Crimson as a new and powerful force of nature. The unholy riff that ushers in this transition is one of the darkest, and most intense in all of rock. Shifting time signatures, throbbing bass, squealing noise, and high drama all combine to make something that sounds like it has been dragged from the darkest pit of hell. Heavy metal has long played with Satanic imagery, but only King Crimson made music which sounded like it was actually played by daemons.

The album takes us on a journey, with structured songs, tight riffs, the beautiful, honeyed tones of Wetton’s singing, and chaotic, improvised elements. It sounds like nothing before, and has rarely been bettered. It ends in a symphony of noise, and when it finally reaches its climax, the effect is both calming and unsettling, like the silence after an argument.

King Crimson hit the road, stretching the songs out into new shapes. The live stage had always been a key part of what the band was about, but this new breed seemed ready to show the world what they were capable of. Using the record as a blueprint, King Crimson blazed a trail across the world, leaving audiences hungry for more. But, as with so much in King Crimson history, the future was never certain.

In later years, Robert Fripp would describe King Crimson as “A way of doing things”, rather than just a band. Jamie Muir no longer wanted to do things the King Crimson way, and so left, to become a monk. Undeterred, Fripp and company carried on, pulling together a series of studio recordings and live improvisations to make their follow-up album, Starless and Bible Black in 1974.

Lark’s Tongues was always going to be tough to follow-up, and Starless struggles in the face of its conceptual brilliance. The live recorded tracks don’t sparkle or fly in the way they’re meant to, and the studio recordings are labyrinthine and cold. Nonetheless, ‘Fracture’ is an intense instrumental that showcases the power of what the band were capable of, and ‘The Night Watch’ has a folk-influenced melody, with John Wetton’s voice painting impressionistic images, as a bed of mellotron conjures a vision of the sleepy English countryside on a hazy winter’s afternoon.

Starless and Bible Black didn’t win the band any new fans, but once again they set out on the road to conquer the stage. And once again, the tour saw the band receive another casualty. With less space for his violin in the increasingly heavy King Crimson sound, David Cross split, leaving just the trio of Wetton, Bruford, and Fripp. Tightening the reins, Fripp regrouped for what was intended as King Crimson’s final hurrah.

Red (1974) opens with a nasty, coiled guitar riff. Bruford’s drums are propulsive, whilst Wetton’s bass is thick, layering on slabs of noise as it locks in with Fripp. This is King Crimson reimagined as a heavy metal monster, the three-piece unleashing dark and brooding rock music, that pummels and threatens, and the results are spectacular.

The first side leans heavily on riffs, big, monolithic things that somehow remain a nimbleness of touch. They sound jagged, but sprightly, not the plodding doom of Black Sabbath, but something else, something tangibly dangerous. Wetton sings of murder in the city streets, and the fear of being in a plane crash, and an aura of tension and paranoia hangs heavy over the music.

The second side stumbles with ‘Providence’, a meandering, ambient instrumental that harks back to the past, showing that the band had perhaps exhausted that particular avenue of inspiration. But the last track, King Crimson’s grand farewell, is an epic, a definitive statement on all that made them the most startlingly original band of their era.

‘Starless’ has little to do with the sound of the album from which it recycles its title. Instead of rough-hewn improvisation, we have brooding layers of mellotron, and melancholic saxophone. John Wetton sings like a man wistfully looking out over the ruins of the earth as the seas boil, and the sky burns. The mood is one of resignation, and regret. But always at the edges of the sound, menace lurks, and when the song builds to a climax, something unexpected happens. The instruments drop out, leaving just Wetton’s slinking bass, and Fripp’s guitar, just hanging on a note, unable, or unwilling to resolve itself.

What follows is one of the greatest passages of instrumental music ever recorded, with all three band members inching the tension and drama of the music ever closer, the calm before the storm erupting into orgiastic violence. Much as Television’s ‘Marquee Moon’ would do a few years later, ‘Starless’ takes one idea and brings it to its logical conclusion, a creep forward which is crushing in its dreadful inevitability. And then it takes it further, beyond the point of comfort. When the Crimson King dies, it leaves you shattered and broken in its wake, desperately wanting more.

After Red, Fripp announced the end of the band. He retreated from public view, intending to go on a permanent sabbatical, a kind of spiritual retreat. However, he was lured back to music through a series of enticing sessions, working with the likes of Peter Gabriel, Daryl Hall, and – perhaps most memorably – David Bowie, contributing the masterful guitar soundscape which elevated ‘Heroes’ into a stone-cold classic.

He would later reconnect with Bill Bruford, and re-launch King Crimson in the 1980s, a very different beast, akin to an artier, more complex Talking Heads, with varying degrees of success. They too would prematurely call it a day, before returning from the dead, and since the 90s, there has almost always been an incarnation of King Crimson, with touring and live performing replacing the records.

In the aftermath of the 1974 split, John Wetton went back to his life as a sideman, playing with Roxy Music and Uriah Heap. Other projects like prog-trio UK failed to re-establish him as a significant force, until a partnership with Yes guitarist Steve Howe, and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer drummer Carl Palmer led to the formation of Asia, a prog-pop supergroup also featuring Geoff Downes of Buggles on keyboards. Sleek, polished, and tight, they crafted modern pop songs at the beginning of the 80s, casting Wetton in a new role, that of a successful stadium rocker, a role to which he quickly warmed.

But for many music fans, the music he made with King Crimson remains not just a high point in his own musical journey, but in the evolution of popular music itself. Active in various musical projects until his death on the 31st of January 2017, Wetton was part of a band for whom music seemed to be more than just a gig.

For a few short years, in the company of Bill Bruford, Jamie Muir, David Cross, and Robert Fripp, John Wetton made music which sounded like the world was ending.

And what a glorious sound it was. Steven Rainey