Paul Thomas Anderson was once asked by Criterion, the American home video distribution company, which three directors had influenced him the most. Anderson replied, “Jonathan Demme, Jonathan Demme and Jonathan Demme.”

Demme was one of the most influential filmmakers of his generation; and certainly one of the most talented. Few directors could shift as effortlessly between filmmaking styles – and as naturally between genres – as Demme, who dabbled fluently in comedy, horror, indie, drama and documentary. But, as well as being incredibly prolific, Demme was also enormously experimental with the medium, pushing cinematic techniques to new levels of sophistication and intelligence. He enhanced methods pioneered by the likes of Hitchcock, such as the use of subjective camera in The Silence of the Lambs, and he experimented with the documentary-style drama to great effect in films like Rachel Getting Married.

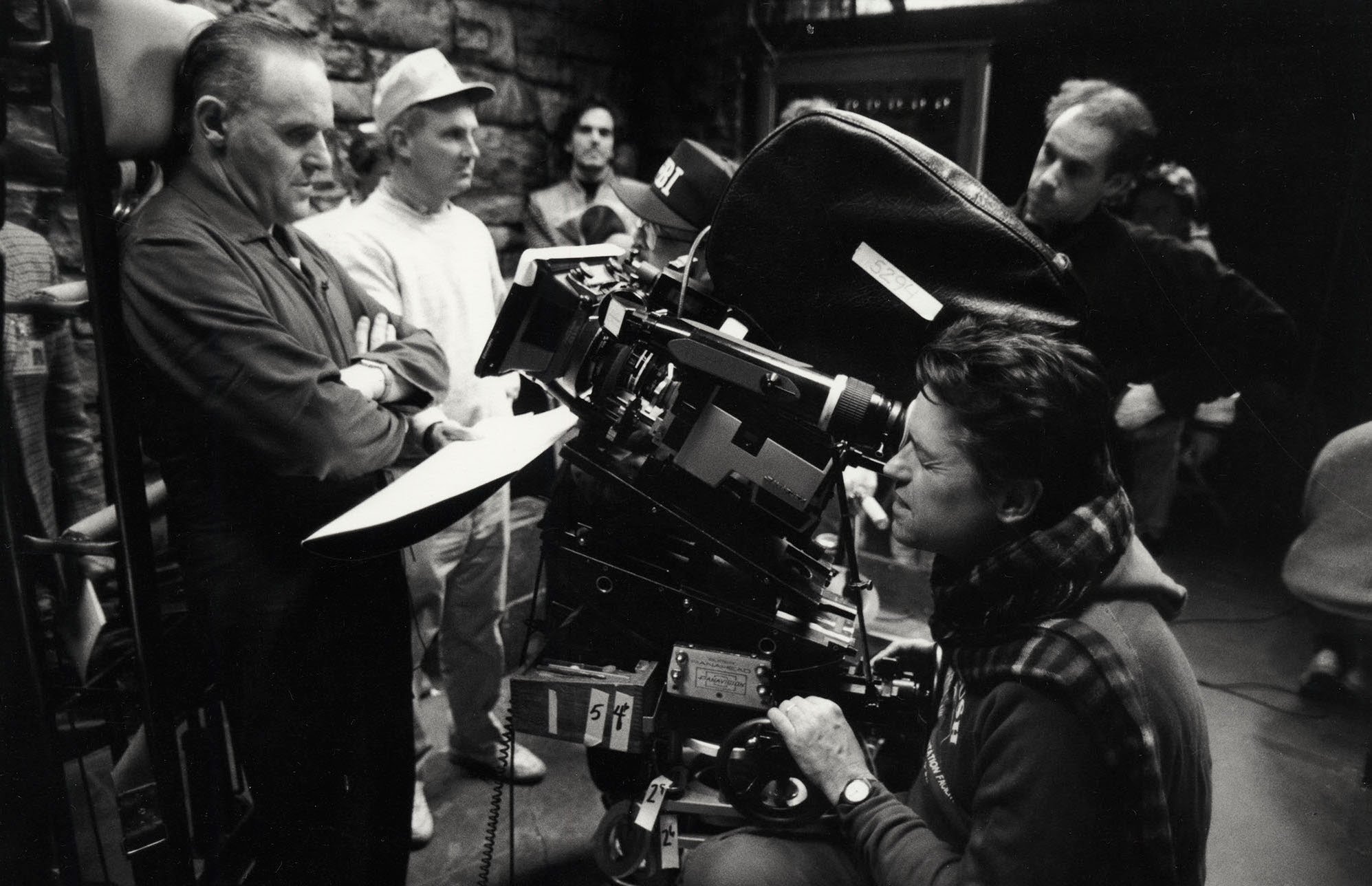

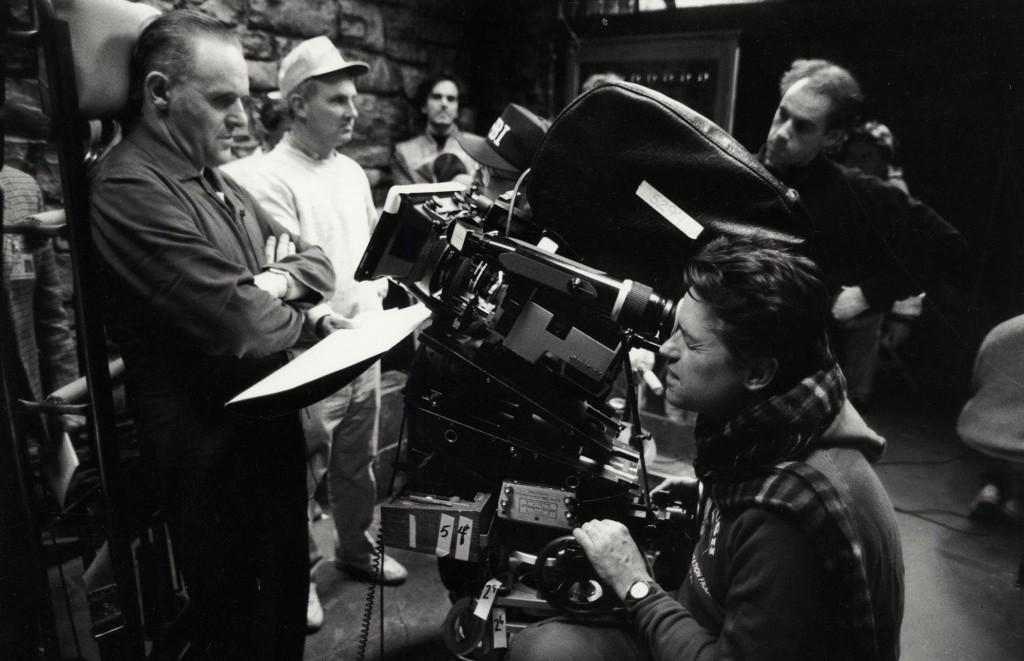

Demme is perhaps best known for directing the Oscar-winning masterpiece The Silence of the Lambs. The film was a sensation upon release and immediately established Anthony Hopkins as a movie star. It also proved that Jodie Foster was one of the best actors of her generation – the plucky, precious kid who spent years out-acting every other adolescent on the screen was now a fully-grown woman whose talent showed no sign of letting up.

The Silence of the Lambs is an exceptionally directed film. It’s a fascinating example of a filmmaker ushering his audience into the mind of a killer – or, more importantly, into the mind of its victim. Demme is forever playing with the audience, forcing them to see the world through differing perspectives, messing with our expectations and sometimes even forcing us to empathise with one of cinema’s greatest villains: Hannibal Lector. It’s a disturbing film; one that astutely depicts a world in which women are objectified in almost every aspect of life, highlighted again through Demme’s genius use of camera subjectivity and POV. (The shot of Clarice Starling in an elevator chalked-full of posturing, physically-dominating men is, in many ways, emblematic of the whole movie.)

Perhaps what made Demme such an inspired choice for directing The Silence of the Lambs was that he cut his teeth working with the exploitation schlock master, Roger Corman. Corman was an early mentor to Demme and imbued in him a profound work ethic and a tremendous respect for populism – one of Demme’s greatest attributes, incidentally; and one that so often gets overlooked when we assess the merits of an artist. His crowd-pleasing mentality, and experience working in low-budget constraints, paved the way for Demme’s indie sensibility of the 1980s – a host of films that mixed the screwball charm of classic ‘30s comedies with the darker, brasher tone of Reaganite America.

This early period of Demme’s career bore some of his best work. Bittersweet films like Melvin and Howard, Something Wild and Married to the Mob showed that he was a filmmaker marked less by stylistic trademarks and more by a certain charitable spirit; a generosity that highlighted his warmness and humanity even when his films delved into darker, more sombre subjects. Something Wild is a great example of this, and to this day is still one of the most underrated films of the ‘80s. It stars Melanie Griffith as the freewheeling Lulu who takes an uptight banker (played by Jeff Daniels) away on a weekend adventure. But all their fun and games subside when Lulu’s husband (a pre-Goodfellas Ray Liotta) finds out what they’re up to. The film is, in essence, a madcap sex comedy – but one with a much darker edge, always delivering its laughs against a subtler, more emotional subtext.

Of course, this early period of Demme’s work also helped establish his marvellous gift for music. Demme was a cinematic shapeshifter – a trait common among classic Hollywood directors of the studio era. Demme’s style, approach and technique continually transformed throughout his eclectic career. However, his remarkable ear for music was perhaps the one factor that remained a constant.

Music was to Demme’s films what suspense was to Hitchcock’s. It was indelible. It was inherent. And it was utterly indispensable. Demme and music simply went hand-in-hand. But this musicality was far from exclusive to his fictional work. Instead it extended all the way into documentary where it flourished to an extraordinary degree. In fact, as this Slate piece by Sam Adams argues, Jonathan Demme was perhaps our greatest director of concert films (although Martin Scorsese is surely in the mix as well). Justin Timberlake + the Tennessee Kids and Neil Young: Heart of Gold are both wonderful examples of Demme’s ability to deconstruct the concert movie and reassemble it into something new; something fresh – something wild.

But Demme’s greatest achievement in this genre (and maybe his greatest achievement altogether) was Stop Making Sense, a concert film about The Talking Heads. Were it not for Prince’s Sign O the Times or Scorsese’s The Last Waltz it might just be the greatest concert movie ever made. The movie opens with David Byrne on stage with an acoustic guitar while members of the band slowly assemble around him, as if props in a movie or pieces of set dressing – again, Demme here being very much interested deconstruction; stripping the band bare and then rebuilding it before our eyes. In a way, this deconstruction was similar to the approach The Talking Heads were taking with regard to their own musical influences around the same time.

After the back-to-back success of The Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia, Demme turned to television, documentaries and shorts – smaller, more intimate projects, generally, although his 1998 adaptation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved was a notable exception. Like so many films of Demme’s career, Beloved is vastly underrated. It’s an admirable adaptation of a book that, like most genius works of literature, does not automatically appear to lend itself easily to the screen. But Demme here does a fine job, injecting the film full of gorgeously powerful images that help bring the novel’s beating pulse to the screen.

“Underrated” is a word that always crops up in a conversation surrounding Jonathan Demme. It’s a testament to his talent and body of work that, despite all of his acclaim and admiration, many of us still feel that a lot of his work is underappreciated. Late-period Demme is a prime example of this. Rachel Getting Married is about a recovering alcoholic who is desperately trying to make it through her sister’s wedding without going insane. The film features perhaps Anne Hathaway’s best performance to date, and the film’s aesthetic was very much inspired by Denmark’s Dogma 95 movement. The film is full of anxiety and distress, but, in typical Demme style, in its final reels it turns into a musical celebration; one wherein its characters find opportunity to dance away the dark. It’s a marvellous film, and one that deserves a larger audience and a wider acclaim.

Rachel Getting Married bears somewhat of a resemblance to Demme’s final fictional feature, Ricki and the Flash: a film about an aging wannabe rock star (brilliantly played by Meryl Streep), who attempts to reconnect with the family she once left behind to pursue her rock ‘n’ roll dream. It’s a sharp, funny and surprisingly touching film that features great live music performances from its actors and a fantastic performance from Mamie Gummer as Julie, Ricki’s daughter (and Streep’s actual daughter in real-life). Like many of Demme’s films, the characters by the end are forced to reconcile with each other; to accept one another’s faults and perhaps find redemption therein. They have to face up to themselves and to each other – and, being a Jonathan Demme movie, that means having to face the music and dance. Jack McFadden @LedZeppJack