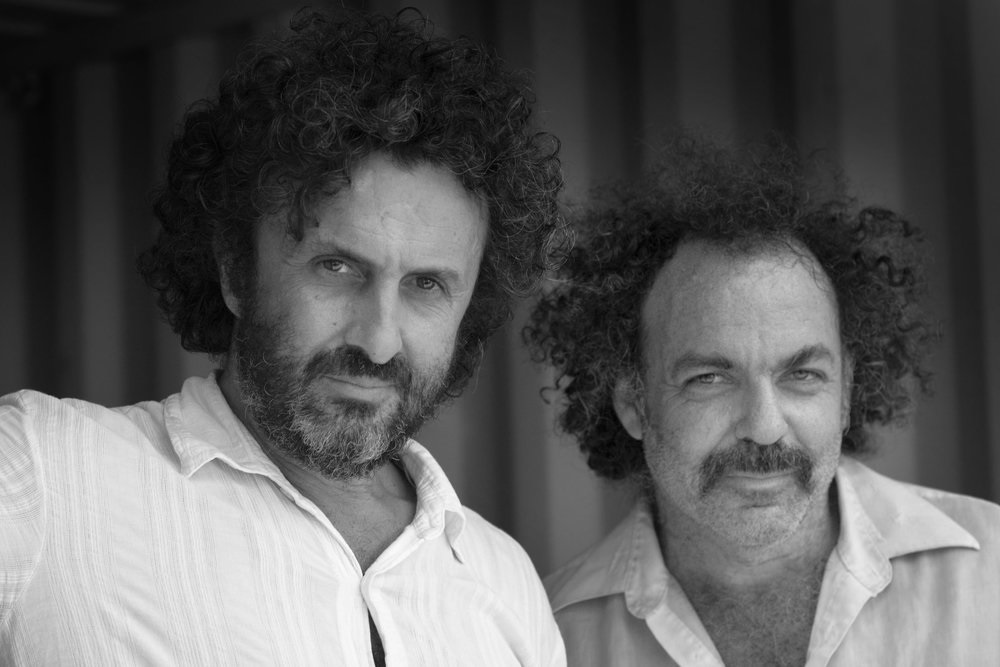

A lute and drum kit doesn’t sound like a combination that should really work, but in this post-genre age almost anything goes. And, when the musicians in question are veritable virtuosos, as is the case with Cretan laouto player George Xylouris and Australian-born, New York-based drummer Jim White, then the results are nothing short of spectacular.

This duo already had a dozen European gigs under its belt in support of its third album, Mother (Bella Union, 2017), which was just as well, as the late arrival of the lute-like lauto-temporarily lost in transit-meant there was no time for a sound-check.

Prior to the main event of the evening, bassist Jack Kelly’s trio played a short set of straight-ahead jazz tunes. The trio’s baptism of fire came at Brilliant Corners in March, and although there have been very few gigs since, there was greater collective energy about this performance.

This increased vim probably had less to do with the fact that the very able drummer Tristan Guillaume was on the stool in place of Jake Homes and more to do with the original material penned by Kelly and pianist Caolan Hutchinson that resulted in their greater emotional investment.

Hampton Hawes’ ‘Blues for Jack’ and Dizzy Gillespie’s samba-esque ‘And Then She Stopped’ bookend a lively set characterized by swing, blues and boppish conventions. The original material–and the playing therein—stood out for being slightly less codified, with Hutchinson in particular catching the ear. These talented young musicians need more opportunities to play and original material may just be the key that opens that door.

Xylouris and White’s music is a compelling blend of folkloric tale and jazz-spirited syncopation. The laouto is most commonly employed as a rhythmic instrument, and whilst Xylouris displayed the sort of rhythmic panache more associated with a flamenco guitarist, in his hands it also became a tool for bravura virtuosity. The endlessly inventive White was very much his equal. Whether Xylouris was strumming up-tempo motifs with his long pick, carving labyrinths of flowing narratives or caressing slower, quasi Early Music melodies, White’s highly empathetic drumming marched in hypnotically close step – an equal weight in the musical balance.

So attuned were the patterns of the drums to the laouto–shadowing, gently embellishing, and splashing sympathetic colors–that the musicians seemed entwined in thought as one. White switched frequently between soft bamboo sticks, brushes and mallets in response to Xylouris’ shifting contours – animated, yearning and then tender. Xylouris’ singing, gruffly lyrical at its most passionate, prayer-like when whispering gravelly, baritone spells, added spice and a sense of intimacy in turn.

The table of Greeks in the audience should have harvested even greater riches through the Greek lyrics and Xylouris’ heartfelt delivery, but they were more engrossed in their own conversations or glued to i-phones. Xylouris responded by playing so softly that their eyes rose to meet his intense glare. This worked in the short term but when they slipped back to their own entertainment Xylouris spoke to them in what was, even to the uninitiated in the Greek language, a polite but firm put-down. And once on board and on the stirring wavelength of the music they contributed great energy to the ambiance with their whoops and yells, even joining in on a traditional Greek song delivered by Xylouris with the hushed gravitas of a lament.

Slowly spun folkloric songs not a million miles from Irish–or India, or Middle Eastern traditions—gathered momentum like a set of reels. At its most fervent, on the exhilarating ‘Black Peak’, lute and drums ploughed giddy, head-spinning courses that would have ignited uninhibited dancing in less sedate, festival crowds. Chairs and tables, however, can act like balls and chains, and the Black Box audiences’ appreciation was limited to cheers and loud applause.

The duo rocked out like an acoustic Rachid Taha, and if North African rai grooves suggested themselves at times, so too did Indian ragas, western rock beats and shuffling, jazz-like rhythms. Certainly White’s versatility on the sticks was joyous to behold, the subtlety of his wrists and the arc of his arms as graceful as any rhythmic gymnast drawing pictures in the air with silk ribbons. White, however, is neither a jazz nor folk drummer; his bag with for twenty five years has been the instrumental indie rock of Dirty Three, his collaborations typically with pop and rock artists like Marianne Faithful, PJ Harvey and Nick Cave. That said, he swung mightily and played with a loose, improvisatory flare that evoked contemporary jazz drummers like Ari Hoenig or David Lyttle.

Two seemingly unconnected musical traditions could appear, on paper at least, as somewhat contrived, but Xylouris and White’s never less than compelling chemistry was as symbiotic as calm and storm, and rang as true as the dawn chorus. As timeless too.

Promotors Moving On Music frequently bring back artists who have impacted its audiences, so it would be a major surprise if Xylouris/White didn’t make a return to Belfast in the not too distant future. Moving On Music, perhaps uniquely, offers a ‘satisfaction or your money back’ policy, such is its faith in the quality of its gigs. With that kind of spirit it’s a wonder that more folk in Belfast don’t take a chance on such uplifting, life-affirming music. Ian Patterson