John Hammond is Steven Spielberg.

Yes, it’s an obvious analogy: Richard Attenborough’s bio-engineering CEO and the maestro who directed him are both bearded childlike innocents, starry-eyed dreamers, alchemists who conjure stunning spectacles for an adoring public and make serious bank in the process. And both have seen their legacy squandered.

In the twenty-five years since Jurassic Park’s release, across four sequels, the parks and their improbable animal attractions have been misused and mistreated, spiralling, in an inevitable logic Dr. Ian Malcolm would appreciate, towards chaos. In this month’s underwhelming Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom a burst of volcanic violence snuffs out Isla Nublar, and the surviving dinos are pillaged by stock villain vulture capitalists. Kingdom did robust work at the box office, and there’s another World on the way, but the franchise feels increasingly exhausted and irrelevant. Can we say… extinct?

How did Spielberg get it so right in 1993 — and how have his successors got it so wrong? Fenced in by bureaucrats and lawyers, and brought low by disaster, Hammond came to sense, if not honestly grasp, his mistake. Spielberg has expressed his own angst, shifting in his later work to questions of heritage, legacy and the common good (Lincoln, The Post and Schindler’s shadow), and tossing his T-Rex into the poisonous pop-culture cocktail of Ready Player One’s, a blockbuster rife with insecurity about what blockbusters have done to us.

But the Fall comes later. First: Creation.

The celluloid equivalent to Hammond’s scientists’ painstaking work of breathing life into bones, Jurassic Park was a miracle made possible by a constellation of technological and human factors: Industrial Light & Magic’s sophisticated effects techniques, the animatronic genius of Stan Winston’s model factory, the trust and financial gamble of Universal Pictures and, at its heart, the vision of someone who knows how movies do their work on us.

Jaws, E. T: The Extra-Terrestial and Indiana Jones had already established Spielberg as the culture’s most invaluable contributor to the multiplex model, but the fresh power of digital effects allowed him to establish new aesthetic and box office precedents for the blockbuster, an upgrade in the gene sequence that astonished audiences all over again.

For critics who lament American cinema’s embrace of action-figure shallowness after the fertile New Hollywood of the ’70s, the triumph of Spielberg and Lucas is a kind of tragedy. But a quarter of a century after Park, the situation is even more dire.

Studios used to make movies about real life, goes the charge, but the Spielbergs only make movies about movies. But that’s manna compared with what we have now: movies about marketing.

Spielberg understood that wonder was a relative quality, to be spooned out in precise measurements, like medication entering the bloodstream. You had to build before you destroy. After Park’s nightmarishly confused opening coda, in which a worker gets dragged to his death by a formless menace, the film asks for our patience before the ‘living attractions’ run amok.

The interminable Jurassic Park III, by contrast, shoves the Allosaurus at us as soon as William H. Macy and co. land on the island, breaking a Tyrannosaur neck in a dino grudge match in a transparent grab for franchise dominance. What all this Super-saurus one-upping — the Indominus Rex, then the Indoraptor — misses is that it’s never been about how big they are, or how many teeth they have, or how many of them there are. It’s about tapping into the lizard brain behind our politeness, the part that runs on fear and threat.

Park grasped the importance of balance: the extraordinary needed the ordinary to give it heft and impact. The conversation on whether or not the film has dated tends to focus on the then-innovative digital effects — sometimes they have, sometimes they haven’t — but what helps keep Park fresh is how analogue it is: the brick and mortar way Spielberg builds his laboriously storyboarded sequences, connecting the characters and the threats through intuitively graspable economy of space, movement and objects.

It’s the details that convince. The way the T-Rex exhales from his nose and blows Alan Grant’s hat off; the thud of the falling land rover on the tree branch above him and Tim; the raspy ‘caw-caw’ of the raptors; the satisfying clunk of Dr. Ellie Sattler pushing the fusebox buttons, counting down to the electric fences. The reliance on sound stages, realistic models and specific plotting — this person must go here to do this — sets up physical stakes and believable causality, the sort of story-telling under-armour you don’t notice until it’s not there.

The park visitors, as proxies for the audience, experience the dinosaurs as events of impossible wonder because they shouldn’t be there. They are a profanity, an intrusion. But this effect only works if you have something to intrude upon. Digital dinosaurs set against a digital background produces no tension, because everything in the frame looks the same.

The story of blockbusters’ weakening hold on our imaginations is also the story of the flight from genre. One of the reasons modern summer movies (Transformers, Independence Day: Resurgence, Kong: Skull Island, Rampage), are so unmemorable is because they rarely stray into genres beyond ‘broadly likeable smashy adventure action’, if we understand genre to mean a conscious deployment of photography, lighting and performances to sell the specific experience of the scene.

Fallen Kingdom’s only striking shots come from its swerve to domestic monster movie in the final act (Spanish director J.A. Bayona having helmed 2007 horror The Orphanage), and The Lost World is sometimes considered the ‘horror’ clone of the first film. But Spielberg was leaning into horror and thriller beats right from the start, as the ooh-ing and ahh-ing turns to running and screaming. Think of the close-ups on eyes and mouths — stunned and terrified faces — or how paranoid lighting turns the park’s control room into a dank and brooding outpost. Or the kitchen hide and seek.

Or Ellie in the trip-switch compound: Arnold’s bloody arm smacking down on her shoulder, the rushing slasher POV shot of the mesh door slamming on the raptor, and the panicky string score as she scrambles away. It’s cheesy — Spielberg is no stranger to the Double Gloucester — but it’s built to communicate panic and terror as efficiently as possible, and give the audience a good time in the process.

Tactile ordinariness extends to the personalities desperately trying to stay off the menu. The characters in Crichton’s novel were flat and fossil-dry, spouting infodump speeches, but Crichton and David Koepp’s script and the perfectly pitched cast bring warmth, wit and believability. Sam Neill’s paleontologist and and Laura Dern’s paleobotanist don’t really look or act like movie stars, coming across like hard-working professionals dragged into a mad situation, managing, without overt romance, to exude an affectionate, earnest connection.

Then there’s Ian Malcolm, the mathematical of a million memes, a Foucauldian Cassandra overflowing with erotic charisma thanks to Jeff Goldblum’s smirking, juttering presence, treating the whole catastrophe as a kind of awful lark, his wry humour balanced by the khaki seriousness of Bob Perk’s game hunter and the chain-smoking nerves of Samuel L. Jackson’s systems engineer.

Attenborough softens the edges of the novel’s Hammond, a greedy Randian industrialist who delivers his sales pitches in Trumpian staccato (The best dinos! Believe me!). Only Wayne Knight’s double-crossing Dennis Nedry, a cackling, fat mess of man, comes close to cartoonish, grounded by garden-variety douchiness (‘you gonna get that?’). Someone like Knight would never get cast in a blockbuster now, where even supporting characters need to clear body aesthetic goalposts.

Spielberg knew he was changing the blockbuster game in 1993. In an interview with Empire magazine he confides his fears about what digital cost-cutting will do to production design, so integral to Park’s convincing reality:

“I don’t think we can ring the death knell on production design this soon,” he says. “But when the time comes where it will be more cost effective to create the sets in a computer as opposed to building the Roman Forum in practical scale, that’s a day I will rue and mourn. And that day is coming — I’ll move into the technology along with everybody else, because that technique will be the only way that filmmakers with big imaginations will be able to afford them.”

That day’s come and gone. The feeling of weightlessness that plagues so many big studio movies isn’t incidental — down to dodgy plotting or bad casting — it’s baked into the structure of modern production. Hollywood has been shifting whole sections of tentpole movies onto ‘pre-vis’ companies, who are staffed with over-worked technicians, hiring directors who won’t make a fuss about style, and coating the final digitally-rendered product in a photographic sheen that looks sharp on the screen but produces no texture.

The difference between Jurassic Park and Jurassic World is that one was made by an artist and the other by a machine.

Spielberg returned to the blockbuster wheelhouse earlier this year with Ready Player One, a glitzy, clumsy adaptation that tried to shift the reference-dense novel’s tone from celebration to warning, or even apology. My review compared it to Fincher’s Fight Club — an act of satirical aggression liable to go over the heads of a sub-culture desperate for validation.

In an Indiewire piece entitled ‘Steven Spielberg Invented The Modern Blockbuster But Ready Player One Suggests He Might Regret It’, David Ehrlich goes further, describing the film as ‘an Ozymandian spectacle by an artist who’s reflecting on his works and despairing over what they’ve wrought. It’s a corporate blockbuster about the corporatization of blockbusters, directed by the man who invented blockbusters […] Spielberg is looking at the mainstream movie culture he helped to create, and desperately trying to fix things before it’s too late.’

Maybe it’s the distortion of hindsight, but Jurassic Park throws up similar disquiet in crude embryonic form, brewing like raptor eggs under warm lab lamps.

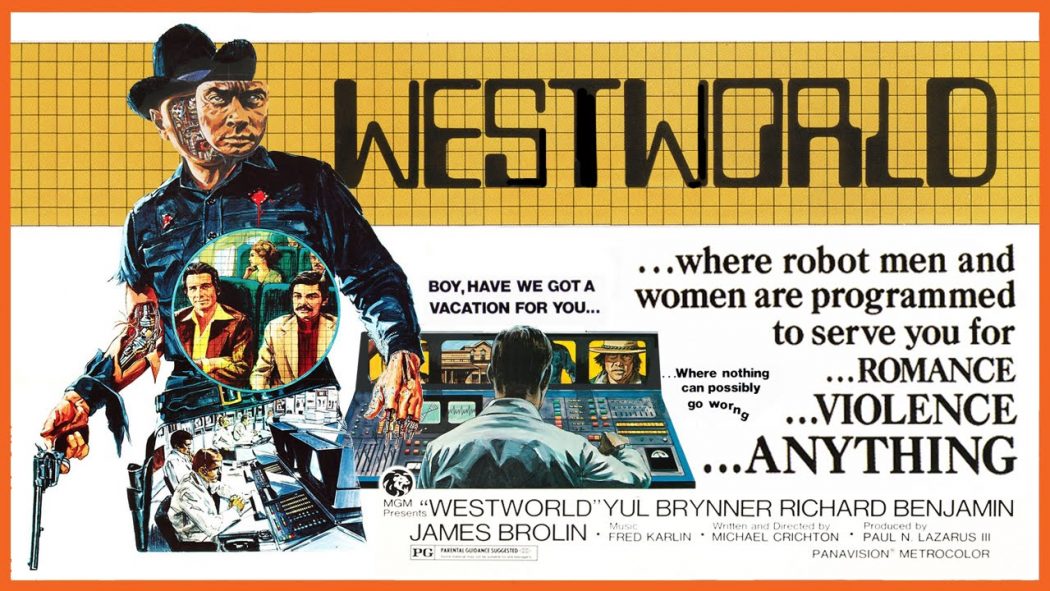

Crichton, novelist and screenwriter, brings his own cynicism. Encouraged by a young Spielberg to make the jump from books to films, his Westworld (1973) melds science-gone-awry fatalism with a pitiless fable about the entitled leisure class getting the retribution they deserve. Its pair of eager tourists — Richard Benjamin’s beta male lawyer and James Brolin’s worldly rogue — are compromised by the entertainment they love, consumed by the animatronic pleasures they’ve paid hard cash to abuse.

Anxieties over money, power, creation and the danger of unintended consequences run through Park. Right after the first shot of the brontosaurus on its hind legs, an archetypal moment of Spielbergian awe, the first dialogue beat is the lawyer’s, murmuring about the fortune the place is going to make. From devotion to mammon, in a heartbeat.

Thanks to hyper-aggressive promotional and tie-in campaigns, merchandise that stood as a token of corporate folly on-screen became sought-after commodities off-screen. Ian slaps down Hammond’s hubris with a speech about the rush to patent, package and slap their accomplishments on a plastic lunchbox, and it’s righteous and accurate and everything, but I had one of those lunchboxes, and I loved it.

Looking back, Jurassic Park feels like peak blockbuster material, a perfection of the form on first go. Partly it’s generational: for those of us born in the late 80’s, Park would’ve been one of the earliest experiences of high-concept, high-effects Hollywood spectacle, the sort of naive astonishment that’s impossible to repeat. Only Christopher Nolan has come close, but his clever conceits tickle the brain rather than the heart.

With its critique of checking out and losing yourself in electronic playpens, Ready Player One showed an attempt at an ethics of escapism, an questioning of blockbuster cinema’s porous place in a wider entertainment culture colonised by easy digital spectacle.

The Hammonds of the tech world hack dopamine systems with carefully curated social feeds. Star Wars jihadis hijack the DMs of an actress they’ve never met and tell her to kill herself, because Asian women can’t be canon. Videogame fanatics make bomb threats to stop feminists sullying the purity of, I don’t know, the new Assassin’s Creed? A reality TV caricature sits in the White House, rotting his Republic from the head down.

The defences are down. The amusements are out of their paddocks.

And they’re gonna eat us. Conor Smyth