Before major label deals and stadium-conquering, mandolin-led ballads were a mere glint in the eyes of Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Bill Berry, there were four men in the college town of Athens. Four men playing music destined to repeat in the Walkman headphones of alienated teens before ‘alienated teens’ became a marketing tool.

Case in point: this very writer discovered Murmur at the age of 16 amongst a select few picks from R.E.M. enthusiastically presented before my eyes by a great friend and diehard aficionado. While Automatic For The People impressed my mother, Monster riffed well enough and I wasn’t ready for New Adventures in Hi-fi just yet, Murmur was precisely what my relatively virgin ears had been waiting to hear. A world of sincere, aesthetic-free alternative music was just opening up.

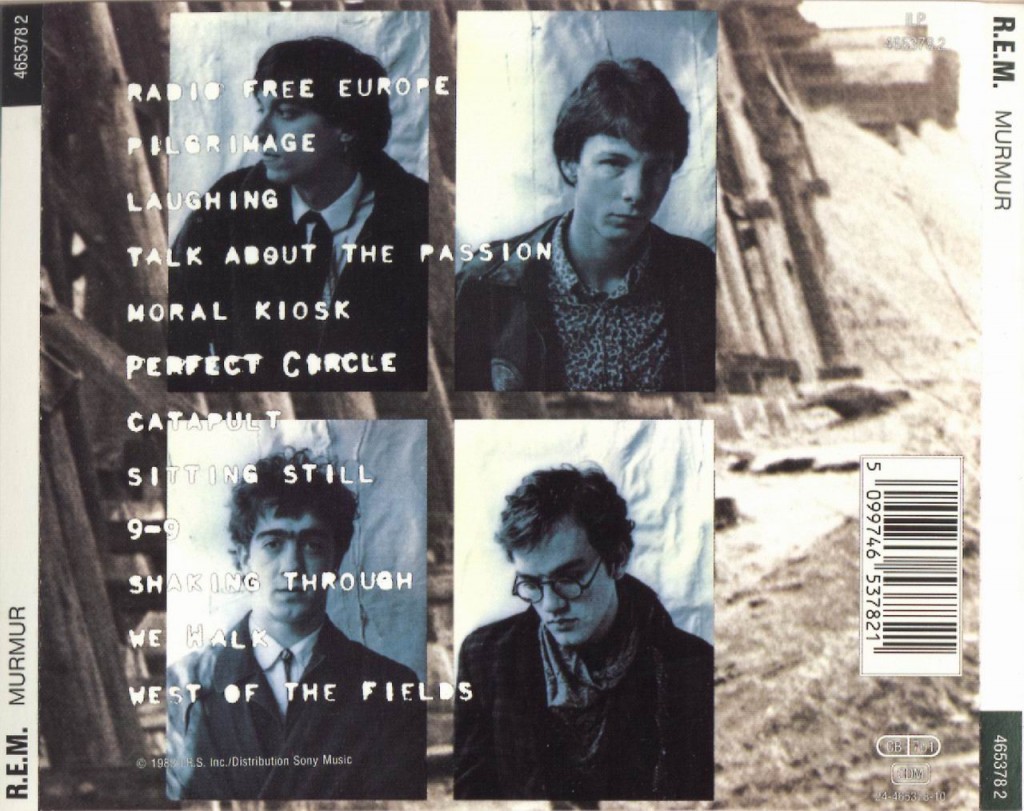

From the blend of the at-times paper-thin moody basslines with Buck’s already-refined signature arpeggiated guitar lines to the beginnings of Stipe’s deeply veiled lyrical content and utterly essential vocal style, Murmur oozes both potential and maturity. It was this early maturity and stubborn (often bullheaded) approach to the recording process that set R.E.M. apart from their closest peers at the time.

Where indie rock acts like The Replacements, Mission of Burma and Hüsker Dü who shared much of the same ethos and trod similar paths – paths without synths or guitar solos, reacting to the punk movement with melody – R.E.M. wanted to create something timeless, and were organised in a democratic way that was unheard of in the circuit. Label and studio advice was being flat-out ignored by the band at this point – including the kudzu-engulfed artwork, which wouldn’t ‘maximise sales potential’ – and they were determined to record the songs with no regard for studio orthodoxy to allow for R.E.M.’s character and vision to be completely articulated on the record. They even had the audacity to go against all of I.R.S. Records’ wishes by bringing definitely D.I.Y. trio The Minutemen out on tour with them in 1985.

From the accidentally recorded hum which segues straight into that four-to-the-floor Berry beat that signals opener ‘Radio Free Europe’, Murmur will take your hand through its chiming, dreamy, weird, cryptic world on its own terms. From the offset, through ‘Pilgrimage’ and ‘Laughing’, the unparalleled melodic telepathy between Peter Buck and Mike Mills are allowed free reign as Berry holds everything together with his measured understanding of what each song requires. The thickly layered vocals fill out an otherwise bright, misleadingly sparse-sounding mix from producer Mitch Easter.

Being the out-and-out ballad on Murmur, ‘Perfect Circle’ hints at future commercial glories from the band, albeit with more obtuse lyrical content compared to the likes of ‘Everybody Hurts’ and ‘Losing My Religion’. ‘Catapult’ and ‘Sitting Still’’s influence can be heard even still on some of the defining documents of Britpop and shoegaze, while ‘9-9’ effortlessly channels the post-punk/art-rock movement with R.E.M.’s stamp of authenticity, which really displays Murmur’s ability to not just be self-contained and characteristic of itself – unique for a debut – but enough has diversity to influence bands from countless genres from 1983 onwards.

Although much has been made of Murmur’s importance in the alt-rock movement, it really can’t be overstated; in 2010, ‘Radio Free Europe’ was added to the National Recording Registry for setting “the pattern for later indie rock releases by breaking through on college radio in the face of mainstream radio’s general indifference”. Were it not for Murmur and R.E.M.’s persistence in the face of everything that was the 1980s, would 1991 ever have happened? It opens up a number of terrifying scenarios. Let’s just rejoice that it did. Stevie Lennox.