In the bifurcated narrative of Stephen King’s 1986 novel It, adapted by Lawrence D. Cohen and Tommy Lee Miller into a two-part TV movie in 1990 and back in cinemas this week with Bill Skarsgård under the Pennywise powder, childhood trauma folds into adulthood fragility. In the second part of the original movie, generally acknowledged to be the weaker of the two, the grown-up Losers Club of Derry, Maine return to their hometown to face Tim Curry’s murderous Dancing Clown, back at it 27 years later. The young friends’ encounters with Pennywise and his shape-shifting forms are vividly dramatised in…

-

-

Taylor Sheridan’s America is an exhausted, shrinking land. Land is a recurring theme for Sheridan, the screenwriter behind two of the best neo-Westerns of recent years, Sicario (directed by Denis Villeneuve) and Hell or High Water (directed by David McKenzie), the latter earning him an Academy nomination. Who owns the land, who takes it, who protects it and — most importantly — what kind of justice is available on it. Both films used frontier geography to tell stories about endings and broken systems, and the moral compromises of righteous avengers. For Wind River, Sheridan directs too. It’s not his directing debut — he did 2011 horror…

-

Right on schedule, it’s 27 years later and we’re back in Derry. It was inevitable that Stephen King’s It, immortalised by Tommy Lee Wallace and Lawrence D. Cohen’s TV movie and Tim Curry’s childhood-scarring circus fiend, would get drawn into the Hollywood remake machine, even if the story’s theme of inter-generational recurrence does at least provide a meta-logic. The first half of Warner Bros’ two-parter, Mama director Andy Muschietti has been tasked with introducing a new generation to King’s Losers Club and the shape-shifting clown that’s buttering them up with sweet, tasty fear. And fair enough: for younger horror fans,…

-

Geremy Jasper, former vocalist of 00’s New York band The Tears, has channeled his younger creative frustrations into feature debut and Sundance hit Patti Cake$, an upbeat tale of an unlikely hip-hop hustler and solid contender for the year’s feel-good rankings. Its got magic indie dust and an against-the-odds underdog ethos and its leads, Danielle Macdonald and Siddharth Dhananjay, two best friends and hip-hop partners, are a memorable and winning double act. Macdonald is Patricia Dombrowski, aka Dumbo, aka Killer P (the titular tag comes later), a plus-size, white, ginger woman desperate for rap glory. Dhananjay is Jheri, an Indian-American who…

-

The one-two punch of last month’s raucous Girls Trip and, now, Rough Night, has sent columnist chins a-stroking about the mainstreaming of the ladette comedy and the gender politics surrounding it. To be fair, the films are noticeably similar in tone and structure, focusing on a group of quasi-estranged old college girlfriends who meet up for an escapist trip of partying, raunchy talk, and bonding. Some have changes in their life they haven’t shared with the others; others have unspoken tensions about adulthood’s diverging priorities. The friends drink, fall out, and make up. (And kill a stripper) Rough Night centres…

-

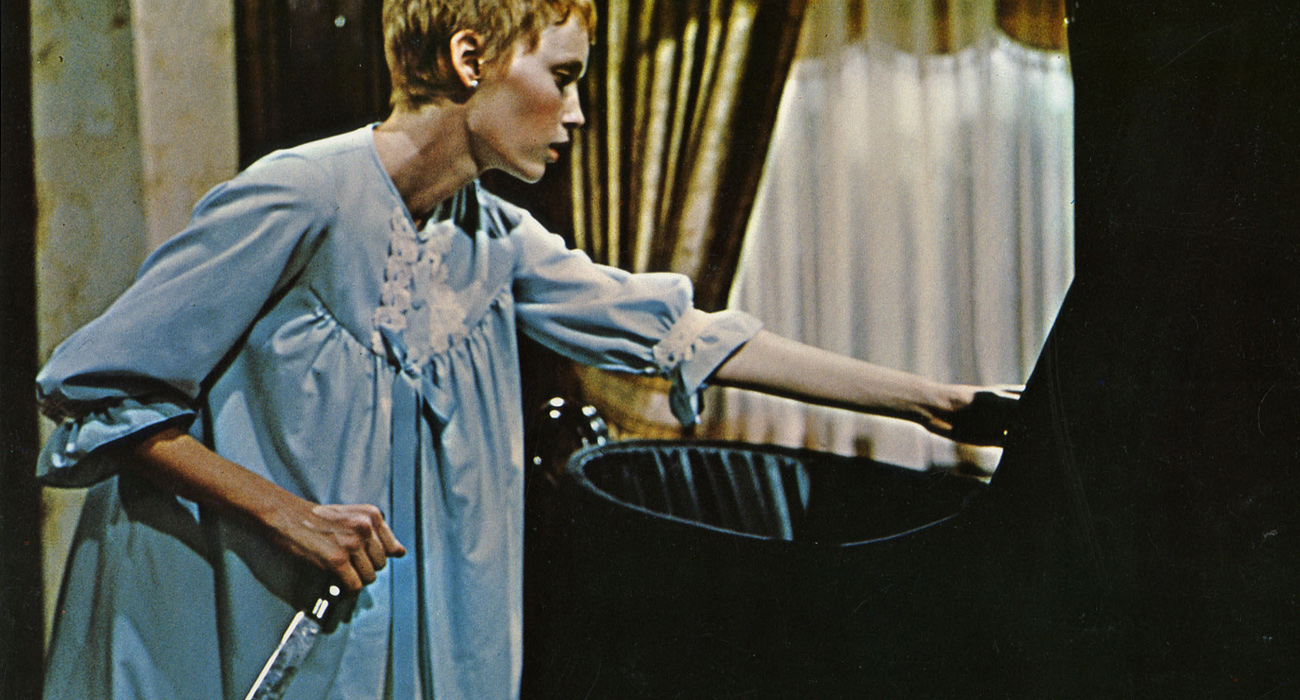

Horror is about the violation of boundaries. To keep life tolerable we parcel up the world in our head, organising experience into handy categories, and the most familiar genre icons signal their disruption: alive/dead (zombies, Frankenstein’s monster), old/new (The Mummy), reality/dreams (Freddy Krueger), animal/man (werewolves). The puss and blood and inside-out, syrupy mess of body horror speaks to a primal fear about the loss of identity and self. Roman Polanski’s 1968 horror classic Rosemary’s Baby, adapted from Ira Levin’s hugely popular novel and screening in the Beanbag Cinema tonight, is organised around a series of boundary violations. Some of these…

-

Final Portrait is actor Stanley Tucci’s fourth film as writer-director and shares with Big Night, his 1996 gastro-drama debut, an interest in artisans and their obsessions; though in comparison, it’s an amuse-bouche. Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti, living in 60s Paris, explains the changes in portraiture philosophy to James Lord, a young American fan and writer who is sitting for one of his own. Portraits used to be finished articles, a frizzle-topped Geoffrey Rush explains, because the subject needed a likeness and a double; the advent of photography has erased that. His portraits are, he admits, essentially unfinished; laboured and inspired…

-

In 2015’s Sleaford Mods: Invisible Britain, film-maker Paul Sng used the Nottingham duo to tell a story about British working class discontent in the age of austerity. His new film, Dispossession: The Great Housing Swindle, takes a longer historical perspective, aiming to examine the failures and dysfunctions of modern British housing. As Maxine Peak’s narration outlines, post-war liberalism championed the country’s new council estates as fulfillments of a democratic promise, ambitious concrete guarantors of secure and dignified shelter. How, the documentary asks, did we get to the present moment, when the term ‘council estate’ is mouthed with a sneer? How…

-

The heroine of young-adult romance Everything, Everything, adapted from Nicola Yoon’s novel of the same name, lives in a bubble. Thanks to a complicated autoimmune condition, Maddie (Amandla Stenberg) is vulnerable to the common bacteria bugs of everyday life. For Maddie’s own protection, her mother, a doctor and her only living family, keeps her inside their specially designed, expensive-looking, air-sealed house. After she got sick as an infant, she’s never ventured outside the home. So she stays inside, reading books and blogs about them on her nice Mac, while dreaming of a life outside of the see-through walls. In concept,…

-

Present-day fans of The Smiths, embarrassed by Morrissey’s descent into unfashionableness, usually preface their admiration with the disclaimer that it’s ‘about the music, not the man’. England is Mine provides the reverse: the man, not the music. Mark Gill’s unlicensed biopic is a portrait of the artist as a moody young man, covering the early stages of Steven Patrick Morrissey’s artistic development, before he began building his first tracks with Johnny Marr (Laurie Kynaston). Basically, it’s a music biopic without the music; in a genre well known for coasting on familiar beats, this is, at least, something new. Played by…